A CGIP1TRES. FALCON I DM. searching for its food, and the shortness of its wings compared

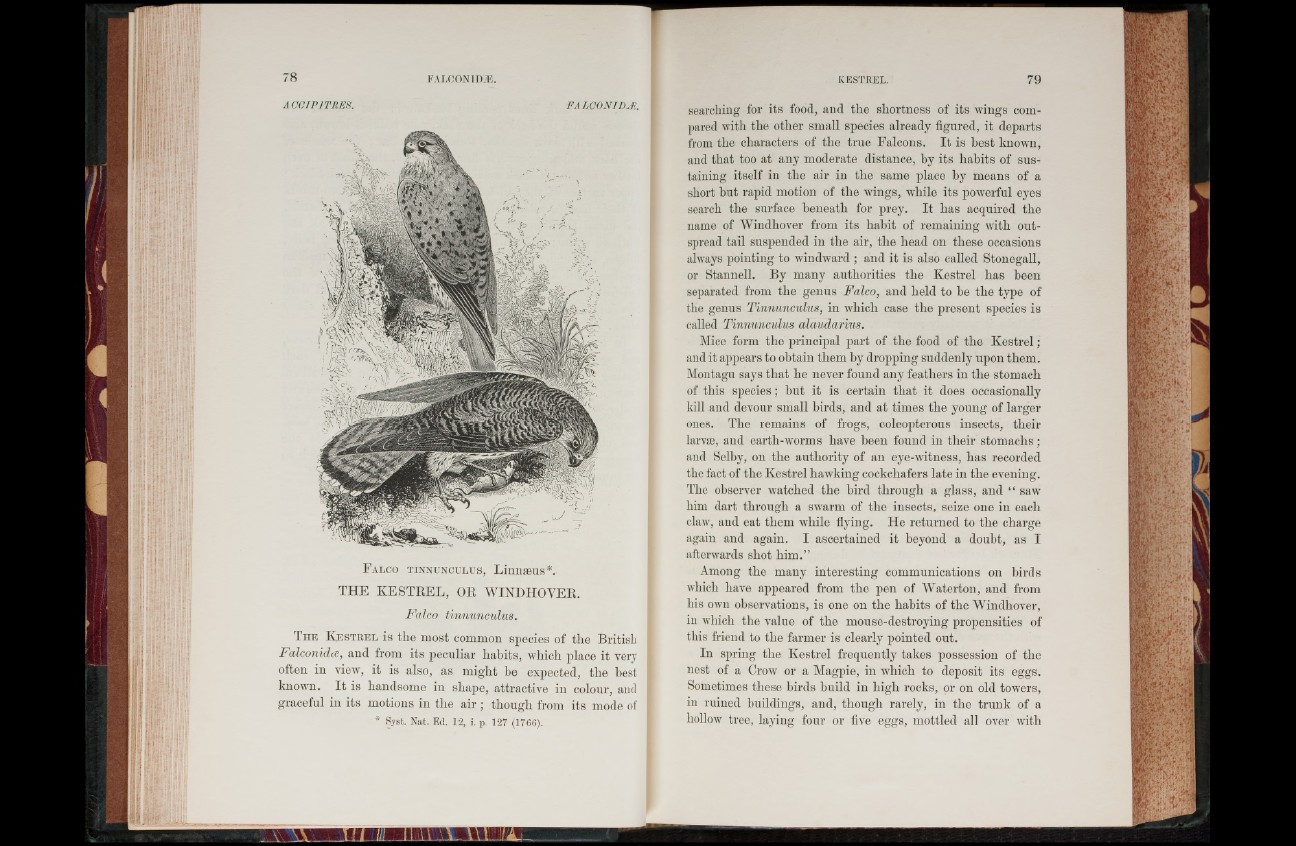

F alco t in n u n c u l u s , Linnaeus*.

THE KESTREL, OR WINDHOVER.

Falco tinnunculus.

T h e K e s t r e l is the most common species of the British

Falconidce, and from its peculiar habits, which place it very

often in view, it is also, as might he expected, the best

known. I t is handsome in shape, attractive in colour, and

graceful in its motions in the air ; though from its mode of

* Syst. Nat. Ed. 12, i. p. 127 (1766).

with the other small species already figured, it departs

from the characters of the true Falcons. I t is best known,

and that too at any moderate distance, by its habits of sustaining

itself in the air in the same place by means of a

short but rapid motion of the wings, wdiile its powerful eyes

search the surface beneath for prey. It has acquired the

name of Windhover from its habit of remaining with outspread

tail suspended in the air, the head on these occasions

always pointing to windward ; and it is also called Stonegall,

or Stannell. By many authorities the Kestrel has been

separated from the genus Falco, and held to be the type of

the genus Tinnunculus, in which case the present species is

called Tinnunculus alaudarius.

Mice form the principal part of the food of the Kestrel;

and it appears to obtain them by dropping suddenly upon them.

Montagu says that he never found any feathers in the stomach

of this species; hut it is certain that it does occasionally

kill and devour small birds, and at times the young of larger

ones. The remains of frogs, coleopterous insects, their

larvie, and earth-worms have been found in their stomachs;

and Selby, on the authority of an eye-witness, has recorded

the fact of the Kestrel hawking cockchafers late in the evening.

The observer watched the bird through a glass, and “ saw

him dart through a swarm of the insects, seize one in each

claw, and eat them while flying. He returned to the charge

again and again. I ascertained it beyond a doubt, as I

afterwards shot him.”

Among the many interesting communications on birds

which have appeared from the pen of Waterton, and from

his own observations, is one on the habits of the Windhover,

in which the value of the mouse-destroying propensities of

this friend to the farmer is clearly pointed out.

In spring the Kestrel frequently takes possession of the

nest of a Crow or a Magpie, in which to deposit its eggs.

Sometimes these birds build in high rocks, or on old towers,

in ruined buildings, and, though rarely, in the trunk of a

hollow tree, laying four or five eggs, mottled all over with