Hume (Ibis, 1871, p. 410) lias lately received an example from

Murdan in the Indus valley; thus proving its southern range

in the Old World to be not much less extensive than it is

known to be in America, where Mr. Dresser records it, on

the late Dr. Heermann’s authority, as having occurred at

San Antonio in Texas (Ibis, 1865, p. 830). On the western

coast of North America, however, its distribution is more

limited, and though it occurs in Vancouver’s Island and

British Columbia, up to the present time Prof. Baird

says it has not been recognized in California. In its

migratory flights the Snowy Owl does not hesitate to betake

itself to the broad ocean: it has more than once been observed

in the Bermudas, and a very interesting account has

been given by Thompson of a flock which accompanied a

ship halfway across the Atlantic from the coast of Labrador

to the North of Ireland. This happened in November,

1838, and it is worthy of remark that not many days after

this event, the example, already mentioned as having

occurred in Devonshire, was picked up dead at St. John’s

Lake, near Devonport. Its skin is now in the collection of

Mr. W. S. Hore of that place.

The Snowy Owl bears confinement well, and in the

aviary of Mr. Edward Fountaine, -whose unrivalled success

in treating tame Owls has before been mentioned, the hen

bird of a pair laid a single egg in the summer of 1870,

and four eggs in that of 1871; but, though she sat on the

latter, no young were hatched.

I t was formerly supposed (as was also imagined to be the

case with the Greenland Falcon) that the first feathers of

the young Snowy Owl were dark in colour, and that the

birds became whiter as they grew older. A specimen of a

nestling in the British Museum negatives this supposition.

The Owlet, it is true, is originally covered with down of a

sooty-black colour, each tuft having a brownish-buff tip ;

but the first feathers assumed are indistinguishable from

those which the adult wears, being of brilliant white with

more or fewer black or very dark brown spots or bars. The

birds, however, vary very much, and in some the plumage

is almost free from dark markings. The variation, as in

the case of the Greenland Falcon, seems to be purely

individual, for specimens of either sex may be obtained

representing its extreme limits, while examples kept in

confinement exhibit no perceptible change consequent upon

age. The dark marks when present are situated towards

the end of the feather; and on the under surface are semi-

lunar in shape, while those on the back and wings are more

linear. The feathers forming the incomplete facial disk,

those of the upper part of the breast, and also the downy

feathers defending the legs and toes, are pure white ; the

beak and claws are black; both are partially hidden by

feathers, and the latter long, curved and very sharp. The

hides are bright orange-yellow. The whole length of the

Snowy Owl is from twenty-two to twenty-seven inches, the

difference depending on the sex: the females are much the

larger of the two.

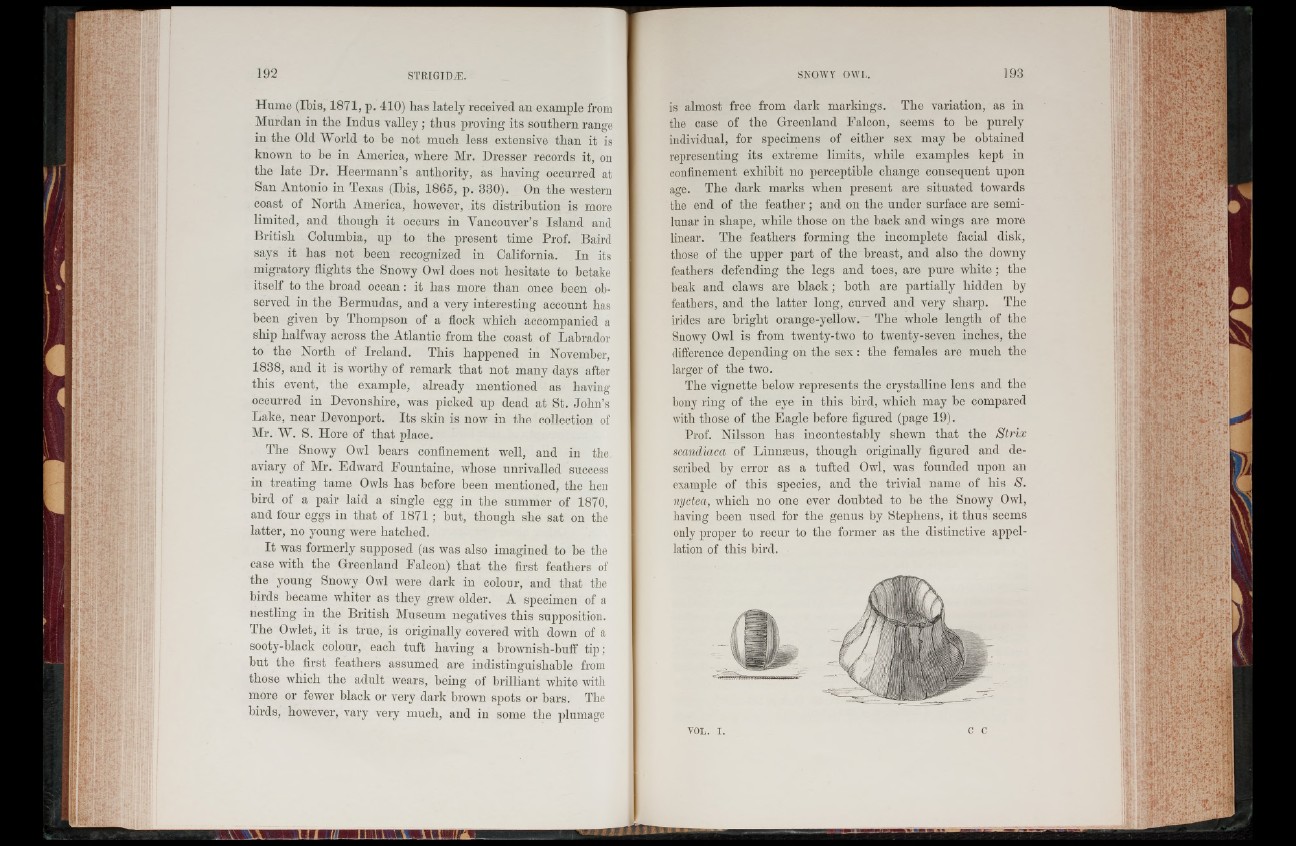

The vignette below represents the crystalline lens and the

bony ring of the eye in this bird, which may be compared

with those of the Eagle before figured (page 19).

Prof. Nilsson has incontestably shewn that the Strix

scandiaca of Linnaeus, though originally figured and described

by error as a tufted Owl, was founded upon an

example of this species, and the trivial name of his S.

nyctea, which no one ever doubted to be the Snowy Owl,

having been used for the genus by Stephens, it thus seems

only proper to recur to the former as the distinctive appellation

of this bird.

von. I. c c

j*v -i, p■ >vf<f e• • p•

KPijfiH,.:

u

I ■ v.T.*: ,• <.’*a .r *4

I

iW?’* VY-:

'

I l i J ®- ,

i s l i

i.lv ; fv.

l i t

V