1 8 FALCONID.E.

species under the name of Aquila barthelemii. They constantly

differ from other Golden Eagles, it is said, hy the

presence of a few white feathers among the scapulars. Two

of these birds, taken from the nest in 1857, were sent to

Mr. Gurney, and one of them, never having before shewn

any departure from the ordinary plumage of A. clirysaetus,

was observed in 1864 to have the first scapular on each side

of a pure white. The Norwich Museum possesses a similar

example from Algeria. Young Golden Eagles, before assuming

the fully mature plumage, often have the feathers

of the tarsus white, and in this state some ornithologists

have been inclined to regard them as belonging to a distinct

species.

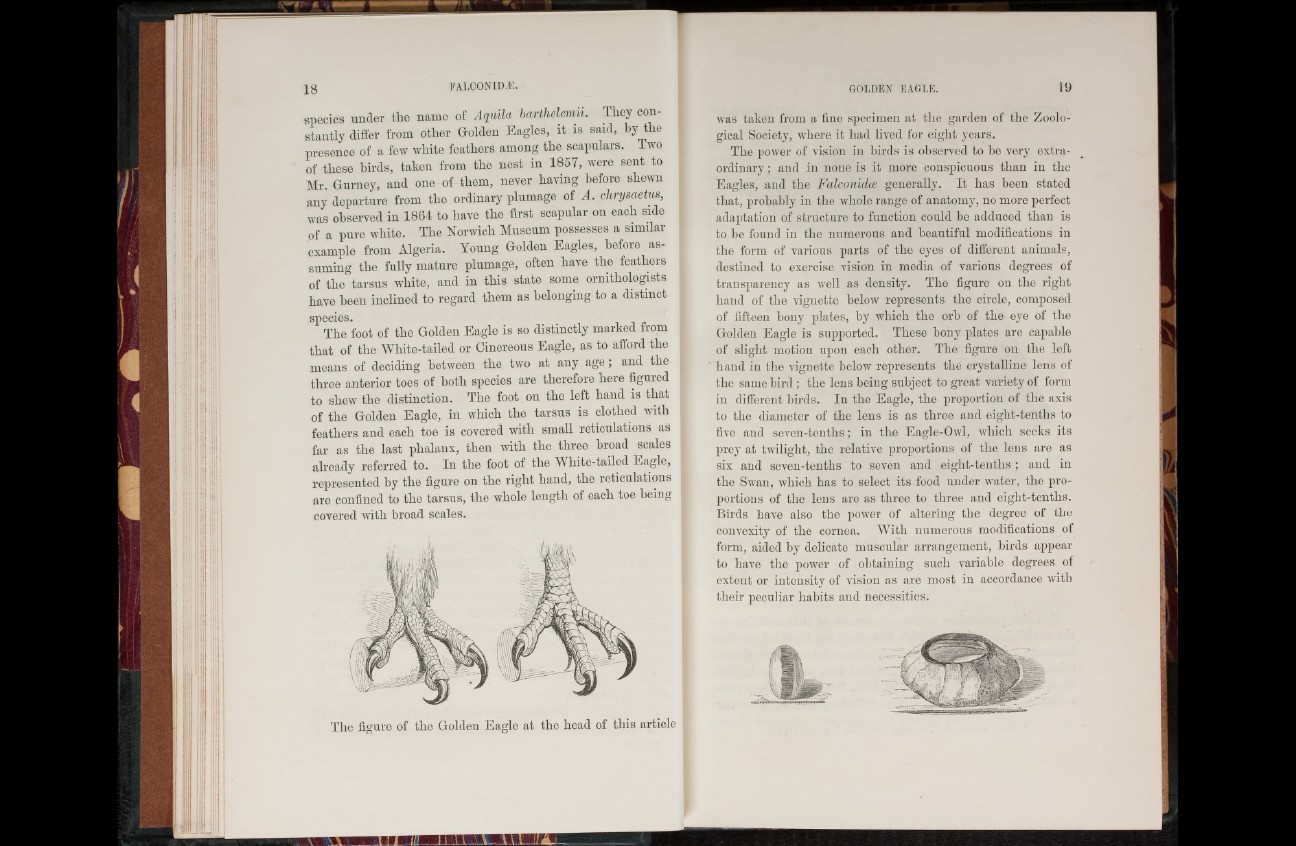

The foot of the Golden Eagle is so distinctly marked from

that of the White-tailed or Cinereous Eagle, as to afford the

means of deciding between the two at any ag e; and the

three anterior toes of both species are therefore here figured

to shew the distinction. The foot on the left hand is that

of the Golden Eagle, in which the tarsus is clothed with

feathers and each toe is covered with small reticulations as

far as the last phalanx, then with the three broad scales

already referred to. In the foot of the White-tailed Eagle,

represented by the figure on the right hand, the reticulations

are confined to the tarsus, the whole length of each toe being

covered with broad scales.

The figure of the Golden Eagle at the head of this article

was taken from a fine specimen at the garden of the Zoological

Society, where it had lived for eight years.

The power of vision in birds is observed to he very extraordinary;

and in none is it more conspicuous than in the

Eagles, and the Falconiclce generally. I t has been stated

that, probably in the whole range of anatomy, no more perfect

adaptation of structure to function could be adduced than is

to he found in the numerous and beautiful modifications in

the form of various parts of the eyes of different animals,

destined to exercise vision in media of various degrees of

transparency as well as density. The figure on the right

hand of the vignette below represents the circle, composed

of fifteen bony plates, hy which the orb of the eye of the

Golden Eagle is supported. These bony plates are capable

of slight motion upon each other. The figure on the left

hand in the vignette below represents the crystalline lens of

the same b ird ; the lens being subject to great variety of form

in different birds. In the Eagle, the proportion of the axis

to the diameter of the lens is as three and eight-tenths to

five and seven-tenths; in the Eagle-Owl, which seeks its

prey at twilight, the relative proportions of the lens are as

six and seven-tenths to seven and eight-tenths; and in

the Swan, which has to select its food under water, the proportions

of the lens are as three to three and eight-tenths.

Birds have also the power of altering the degree of the

convexity of the cornea. With numerous modifications of

form, aided by delicate muscular arrangement, birds appear

to have the power of obtaining such variable degrees of

extent or intensity of vision as are most in accordance with

their peculiar habits and necessities.