of rock at various elevations on the seaward face of a cliff,

often choosing, in accordance with the nature of the locality,

a recess under a stone, a tuft of grass, moss or other plants

characteristic of a maritime situation, to afford additional

shelter. The nest is made up of several sorts of dry grasses

mixed sometimes with seaweeds, and is lined with finer

materials of the same kind together with some hair when it

can be got. The eggs are four or five in number, variable in

colour, presenting two types—one reddish-brown, the other

olive, but with many intermediate phases: the ground is

french-white, sometimes with a decidedly green tinge, and is

usually closely mottled or suffused and at times marbled with

darker markings of some shade of reddish-brown, olive or

brownish-grey. The eggs measure from '89 to '78 by from

•67 to ’61 in. There are commonly two broods in the season

and the young of the first are hatched early in spring.

The Rock-Pipit is a constant inhabitant of nearly all the

shores of the United Kingdom, breeding in the manner just

described along the whole coast-line of England with the

remarkable exception of that part which lies between the

Thames and the Humber, where it would seem to occur

only on passage ; for though resident as a species it is, like

so many of our birds, migratory as an individual. In Scotland

and Ireland however no such exception is known, and it

is found commonly everywhere and at all seasons on their

coasts as well as on those of their adjacent and out-lying

islands, even to St. Kilda and Shetland. I t is also abundant

in the Faroes, but is not known in Iceland or Greenland.

On the European continent, the distribution of our Rock-

Pipit is not very easily traced, and the fact must be recorded

that examples from most parts of Scandinavia, and probably

from the shores of the Baltic generally, present a rufous or

vinous colouring on the breast, inducing some ornithologists

to regard them as forming a distinct species to which the

name of Antlius rupestris, conferred in 1817 by Prof. Nilsson

(Orn. Svec. i. p. 245), should perhaps be applied. These ruddy

birds, as might be expected, occasionally visit England and

have most likely given rise to the confusion existing in years

----------

gone-by as to a so-called “ Red L a rk ”—the Alauda rubra of

older writers—said to occur in this country, while several

British authors, even the accurate Macgillivray among the

number, have confounded them with the North-American

Pipit, Antlius ludovicianus—a species not as yet proved to

have been observed in Britain. More recently other English

ornithologists have seen in them examples of the European

A. spipoletta, just described. From either of the species last

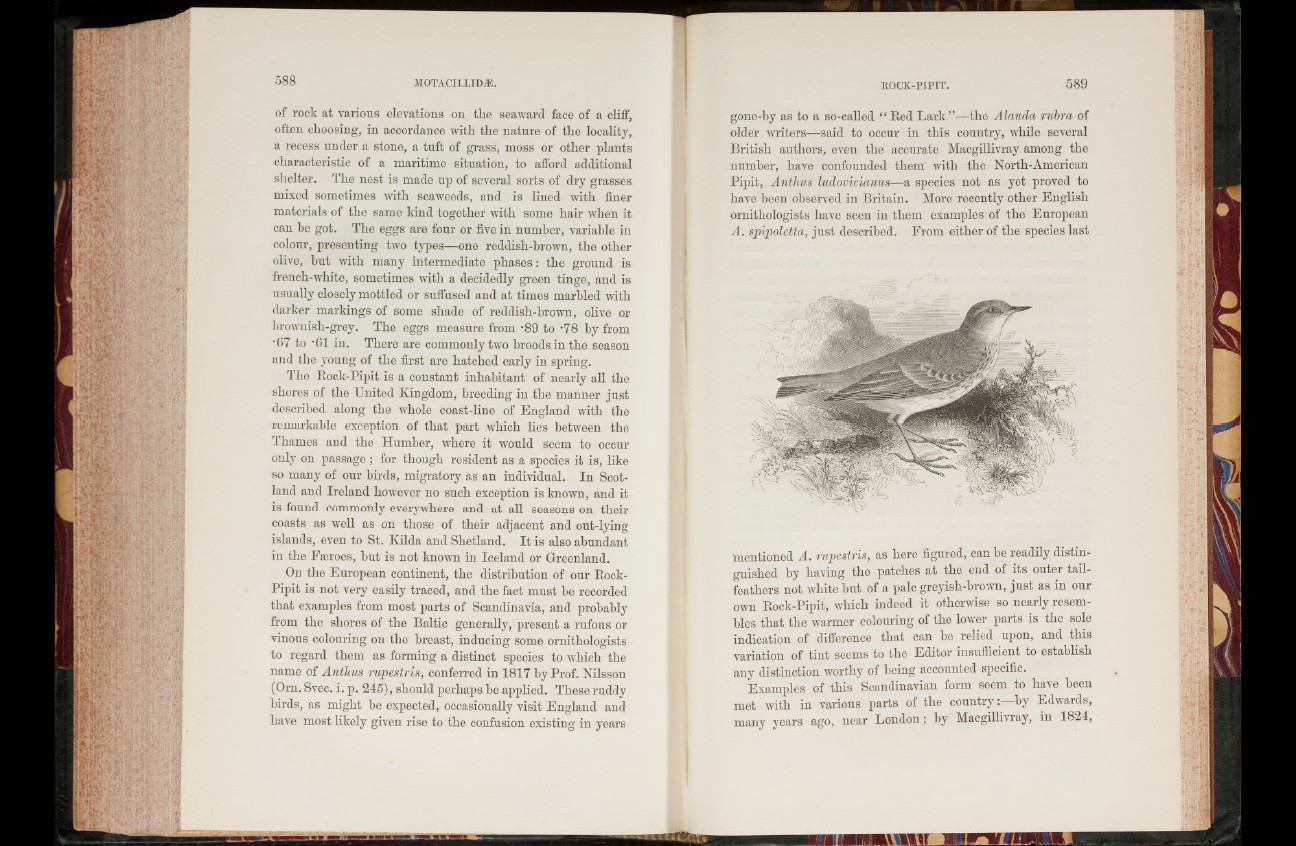

mentioned A. rupestris, as here figured, can be readily distinguished

by having the patches at the end of its outer tail-

feathers not white but of a pale greyish-brown, just as in our

own Rock-Pipit, which indeed it otherwise so nearly resembles

that the warmer colouring of the lower parts is the sole

indication of difference that can be relied upon, and this

variation of tint seems to the Editor insufficient to establish

any distinction worthy of being accounted specific.

Examples of this Scandinavian form seem to have been

met with in various parts of the c o u n t r y b y Edwards,

many years ago, near London; by Macgillivray, in 1824,