The male has the bill dusky, with horn-coloured edges:

the irides dark hazel: the forehead and a line running backward

over each eye, so as to completely encircle the head,

white, the crown of the head blue, light in front and darker

behind ; a hand of dusky blue runs from the nostril to the

eye, and thence above each ear-covert to the nape, whence it

descends, on either side of the neck, behind the cheeks,

which are white; behind this hand the nape is whitish; the

mantle, rump and upper tail-coverts are yellowish-green;

wings and tail blue ; the greater wing-coverts and the tertials

tipped with white ; the chin and throat are of a bluish-black,

which meets the dark hand of the sides of the neck; the

breast, belly and flanks, sulpliur-yellow, with a mesial stripe

of bluish-black on the first wing- and tail-feathers beneath,

pearl-grey: legs, toes and claws, bluish-grey.

The whole length is four inches and a half. From the

carpal joint to the end of the wing, two inches and three-

eightlis ; the third and fourth primaries equal and longest.

In winter the dark patch on the throat is mottled with

white. The female is less bright in colour than the male.

The young are marked like the adults, but all their tints are

more dingy, and their plumage is suflused with yellow.

By Kaup this bird, with the Parus cyanus of Eastern

Europe and Siberia, has been removed to a genus Cyanistes,

which, in the case of the former at least, is quite unnecessary.

The fondness for flesh and fat which, as mentioned above,

the Bluecap shews is shared by other species of the genus

Parus, and many persons who delight in watching the actions

of these lively little birds attract them to spots where they

can be conveniently observed by ministering to this taste.

No mode of enticing them is better than that of hanging a

lump of suet or tallow by a short string to the end of a flexible

rod stuck aslant into the ground close to the window of a

sitting-room. I t is seldom long before a Titmouse of some

kind finds the dainty, and once found visits are constantly

made to it until every morsel is consumed. No other bird

can succeed in keeping a foothold on the swinging lure, but

the strong grasp of a Titmouse renders the feat easy for him.

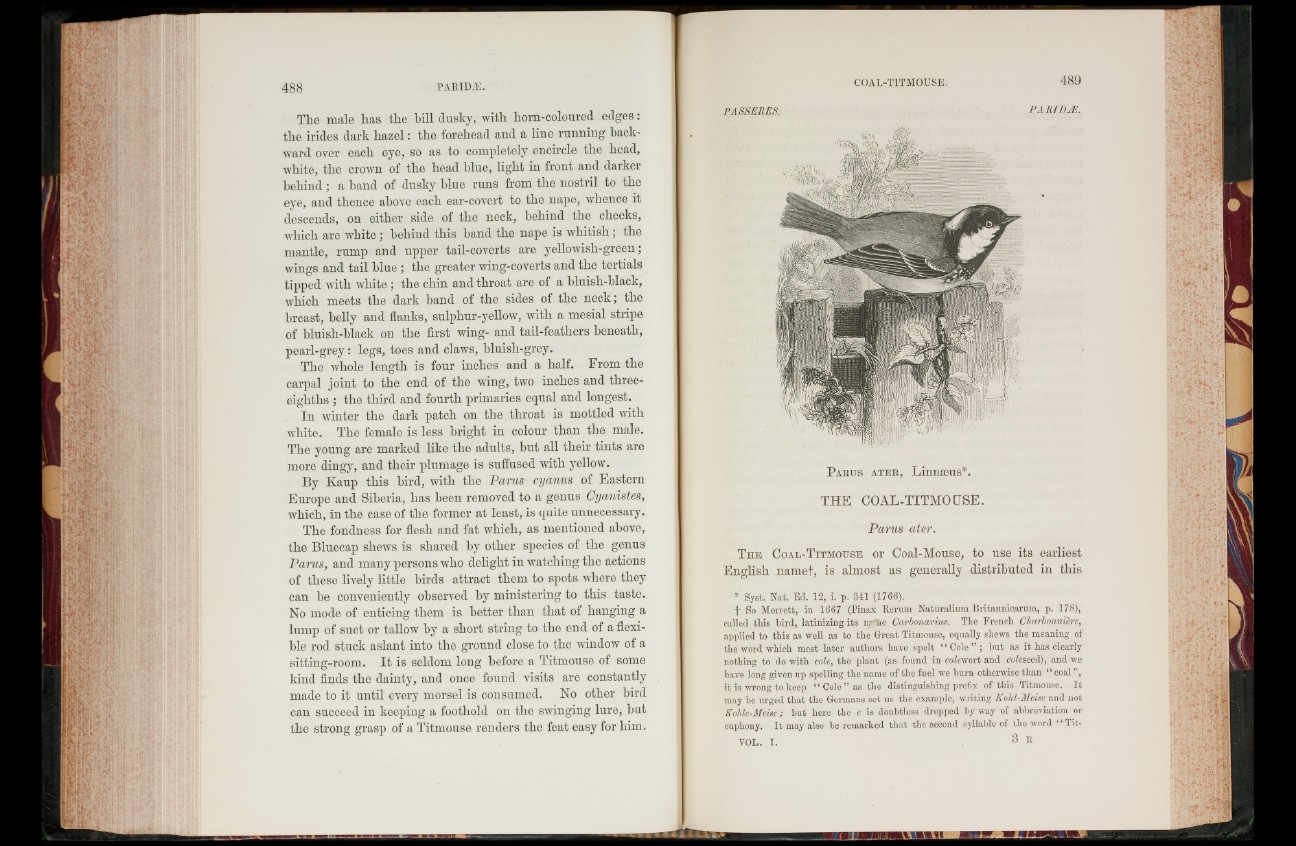

P A S S ERES. P A R IDÆ .

P a ru s a t e r , Linnæus*.

THE COAL-TITMO USE.

Parus ater.

T h e C o a l -T itm o u s e or Coal-Mouse, to use its earliest

English namet, is almost as generally distributed in this

* Syst. Nat. Ed. 12, i. p. 341 (1766).

f So Merrett, in 1667 (Pinax Reram Naturaliura Britannicarum, p. 178),

called this bird, latinizing its nr-'ne Carbonarius. The French Charbonnière,

applied to this as well as to the Great Titmouse, equally shews the meaning of

the word which most later authors have spelt “ Cole'’ ; hut as it has clearly

nothing to do with cole, the plant (as found in cole wort and coZcseed), and we

have long given up spelling the name of the fuel we burn otherwise than “ coal ”,

it is wrong to keep “ Cole” as the distinguishing prefix of this Titmouse. I t

may be urged that the Germans set us the example, writing Kohl-Meise and not

Kohle-Meise ; but here the e is doubtless dropped by way of abbreviation or

euphony. I t may also be remarked that the second syllable of the word “ Tit-

VOL. I . 8 R