I t will now however be within the knowledge of most

ornithologists that these so-called “ laws ” are subject to

numerous exceptions, while they by no means include all

the different cases which an extended acquaintance with the

feathered creation will shew. The first of them when taken

according to the precise terms in which it was enunciated

seems to have the most force, but cases occur, as in some

of the Woodpeckers, where the young have a plumage peculiar

to themselves even when that of their parents differ sexually;

and we ought also to take up the converse of the proposition,

where we find that in the rare cases in which the female

possesses more lively colours than the male, the young of

both sexes resemble him. To the second of these “ laws ”

exceptions are more plentiful even among common British

birds; for in many of the Crows and in the Kingfisher,

where the sexual differences of the adults are exceedingly

slight, the young have no plumage that can be called peculiar

to themselves. Nor are cases far to seek in which the

third “ law ” will not apply ; for in the Razor-bill and the

Common Guillemot, where the breeding plumage of both

sexes is alike and yet decidedly different from that which

they wear in winter, the first plumage of the young resembles

the wedding garments of their parents without possessing

anything of an intermediate character between the two

periodical states. Again there are instances in which both

adults and young differ according to sex, thus the male

Blackbird can be distinguished from the female even as a

nestling. All these cases have been very fully' considered

by Mr. Darwin in his latest work, and, quite irrespective of

any arguments that may be founded upon them, the chapter

in which they are treated deserves the closest attention of

ornithologists.*

Into the question of the various modes by which changes

in the appearance of the plumage of birds are produced it

is not proposed at present to enter.

* ‘ The Descent of Man, and Selection in relation to Sex.’ London: 1871,

vol. ii. chap. xvi. pp. 187-223.

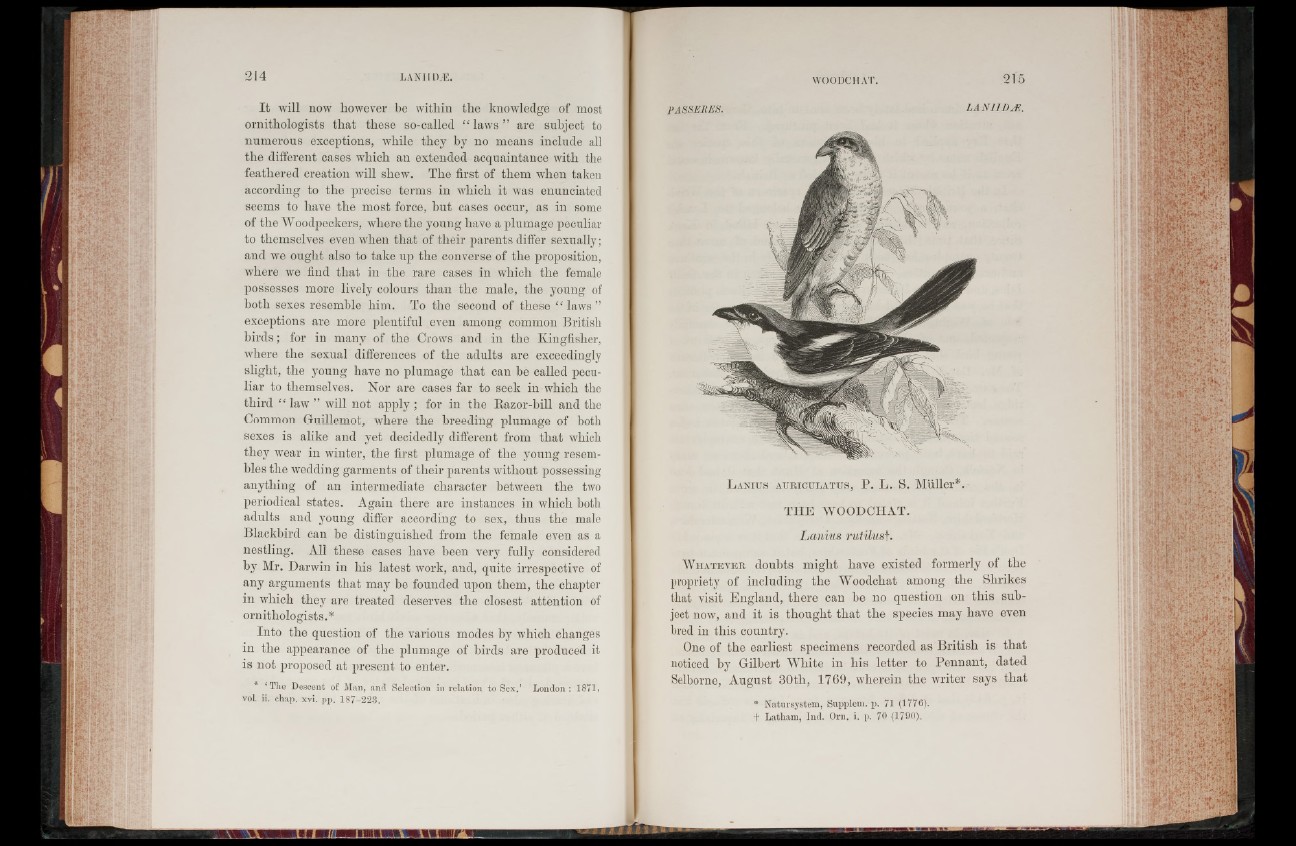

P ASSURES. LAN1IDÆ.

L a n iu s a u r ic u l a t u s , P. L. S. Muller*.

THE WOODCHAT.

Lanius rutilus\.

W h a t e v e r doubts might have existed formerly of the

propriety of including the Woodchat among the Shrikes

that visit England, there can he no question on this subject

now, and it is thought that the species may have even

bred in this country.

One of the earliest specimens recorded as British is that

noticed by Gilbert White in his letter to Pennant, dated

Selborne, August 30tli, 1769, wherein the writer says that

* Natursystem, Supplem. p. 71 (1776).

f Latham, Ind. Orn. i. p. 70 (1790).