384 SYLV1 ID.TI.

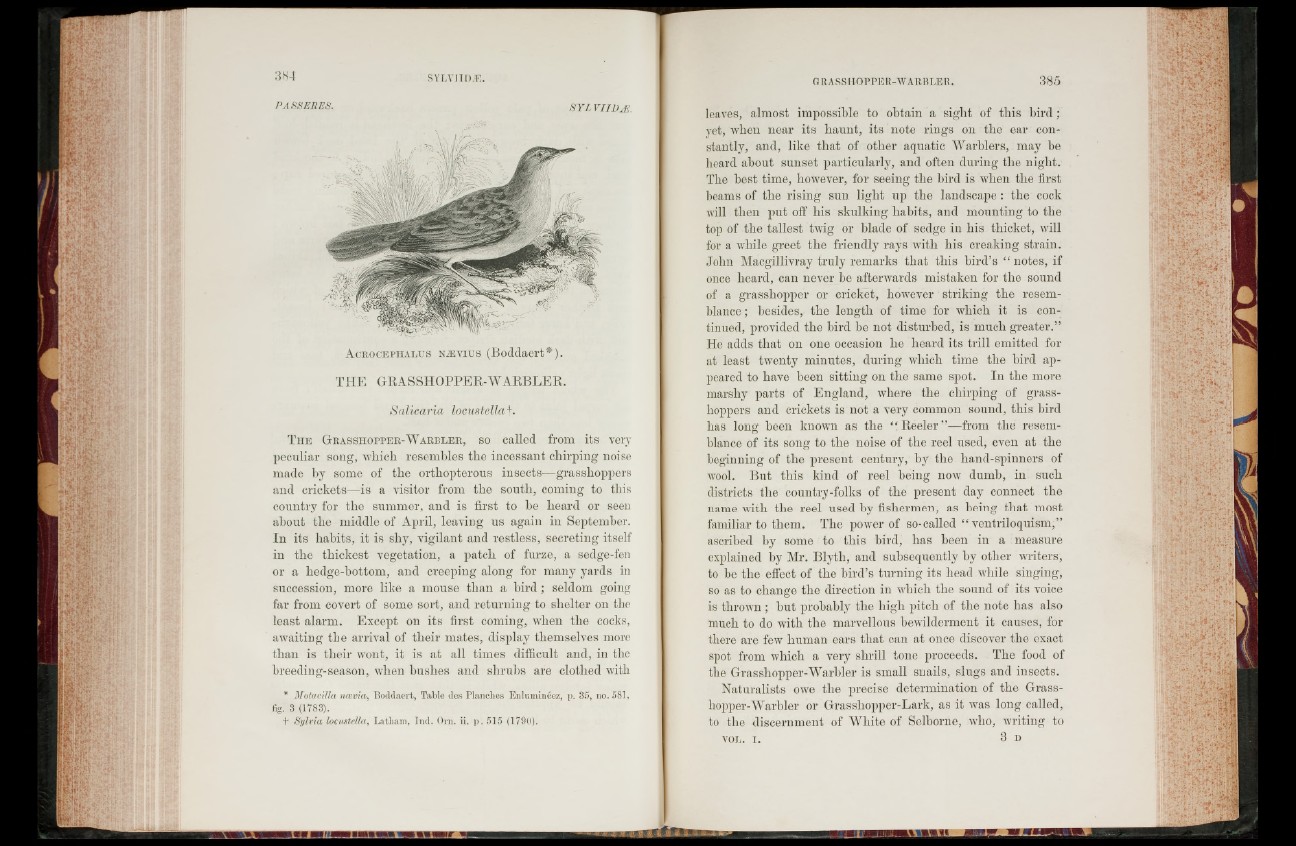

A c r o c e p h a l u s NíEv iu s (Boddaert*).

THE GRASSHOPPER-WARBLER.

Salicaria locustella\.

T h e G r a s s h o p p e r -W a r b l e r , so called from its very

peculiar song, which resembles the incessant chirping noise

made by some of the orthopterous insects—grasshoppers

and crickets—is a visitor from the south, coming to this

country for the summer, and is first to be heard or seen

about the middle of April, leaving us again in September.

In its habits, it is shy, vigilant and restless, secreting itself

in the thickest vegetation, a patch of furze, a sedge-fen

or a hedge-bottom, and creeping along for many yards in

succession, more like a mouse than a b ird ; seldom going

far from covert of some sort, and returning to shelter on the

least alarm. Except on its first coming, when the cocks,

awaiting the arrival of their mates, display themselves more

than is their wont, it is at all times difficult and, in the

breeding-season, when bushes and shrubs are clothed with

* Motacilla n a s v iaBodclaert, Table des Planches Enlumincez, p. 35, no. 581,

fig. 3 (1783).

t Sylvia locustella, Latham, Ind. Orn. ii. p. 515 (1790).

\ \ ^ i l l ui i > \ i \ m i i i

G RA SS liOPPE ll-W A R BLE R. 385

leaves, almost impossible to obtain a sight of this bird ;

yet, when near its haunt, its note rings on the ear constantly,

and, like that of other aquatic Warblers, may be

heard about sunset particularly, and often during the night.

The best time, however, for seeing the bird is when the first

beams of the rising sun light up the landscape : the cock

will then put off his skulking habits, and mounting to the

top of the tallest twig or blade of sedge in his thicket, will

for a while greet the friendly rays with his creaking strain.

John Macgillivray truly remarks that this bird’s “ notes, if

once heard, can never be afterwards mistaken for the sound

of a grasshopper or cricket, however striking the resemblance

; besides, the length of time for which it is continued,

provided the bird be not disturbed, is much greater.”

He adds that on one occasion he heard its trill emitted for

at least twenty minutes, during which time the bird appeared

to have been sitting on the same spot. In the more

marshy parts of England, where the chirping of grasshoppers

and crickets is not a very common sound, this bird

has long been known as the “ Reeler”—from the resemblance

of its song to the noise of the reel used, even at the

beginning of the present century, by the hand-spinners of

wool. But this kind of reel being now dumb, in such

districts the country-folks of the present day connect the

name with the reel used by fishermen, as being that most

familiar to them. The power of so-called “ ventriloquism,”

ascribed by some to this bird, has been in a measure

explained by Mr. Blyth, and subsequently by other writers,

to be the effect of the bird’s turning its head while singing,

so as to change the direction in which the sound of its voice

is thrown ; but probably the high pitch of the note has also

much to do with the marvellous bewilderment it causes, for

there are few human ears that can at once discover the exact

spot from which a very shrill tone proceeds. The food of

the Grasshopper-Warbler is small snails, slugs and insects.

Naturalists owe the precise determination of the Grasshopper

Warbler or Grasshopper-Lark, as it was long called,

to the discernment of White of Selborne, who, writing to

VOL. I. 3 d