A CCIPTTRES. p A LCONIDJi.

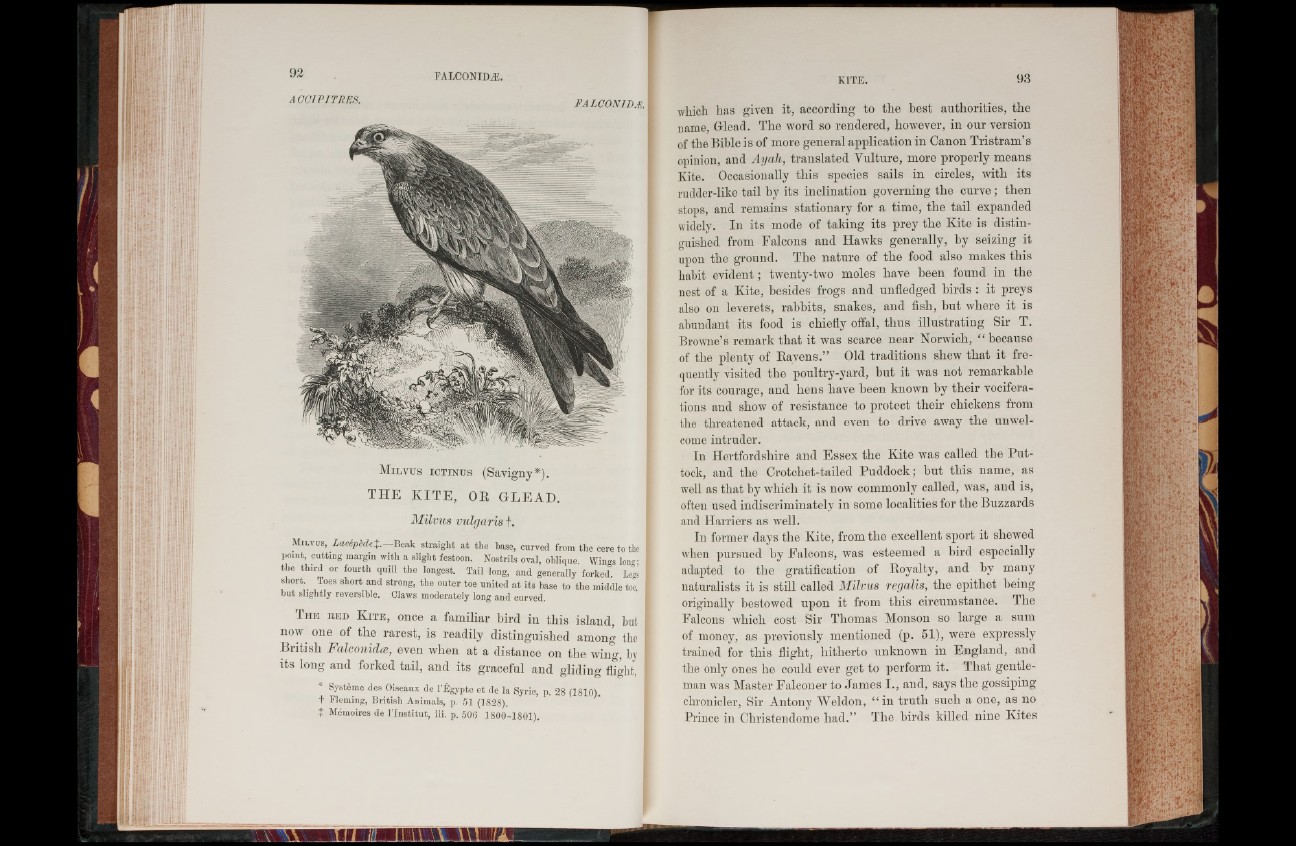

M il v u s ic t in ü s (S a v ig n y * ).

TH E K IT E , OR O L EA D .

Milvus vulgaris f.

M i l v u s , Lacépèdet—Beak straig h t a t th e base, curved from the cere to the

point, cutting margin with a slight festoon. Nostrils oval, oblique. Wings Ion« ■

the th ird or fourth quill th e longest. Tail long, and generally forked. Legs

shorty Toes short and strong, th e oute r toe united a t its base to th e middle toe

b u t slightly reversible. Claws moderately long and curved.

T h e b e d K i t e , o n c e a f a m i l i a r b i r d i n t h i s i s l a n d , but

n ow o n e o f t h e r a r e s t , i s r e a d i ly d i s t i n g u i s h e d a m o n g the

B r i t i s h Falconidoe, e v e n w h e n a t a d i s t a n c e 011 t h e w in g , by

i t s lo n g a n d f o r k e d t a i l , a n d i t s g r a c e f u l a n d g l i d i n g flight,

* Système des Oiseaux de l’Égypte et de la Syrie, p. 28 (1810).

t Fleming, British Animals, p. 51 (1828).

î Mémoires de l’In s titu t, iii. p. 506 1800-1801).

which has given it, according to the best authorities, the

name, Glead. The word so rendered, however, in our version

of the Bible is of more general application in Canon Tristram’s

opinion, and Ayah, translated Vulture, more properly means

Kite. Occasionally this species sails in circles, with its

rudder-like tail by its inclination governing the curve; then

stops, and remains stationary for a time, the tail expanded

widely. In its mode of taking its prey the Kite is distinguished

from Falcons and Hawks generally, by seizing it

upon the ground. The nature of the food also makes this

habit evident; twenty-two moles have been found in the

nest of a Kite, besides frogs and unfledged birds : it preys

also on leverets, rabbits, snakes, and fish, but where it is

abundant its food is chiefly offal, thus illustrating Sir T.

Browne’s remark that it was scarce near Norwich, “ because

of the plenty of Ravens.” Old traditions shew that it frequently

visited the poultry-yard, but it was not remarkable

for its courage, and hens have been known by their vociferations

and show of resistance to protect their chickens from

the threatened attack, and even to drive away the unwelcome

intruder.

In Hertfordshire and Essex the Kite was called the Put-

tock, and the Crotchet-tailed Puddock; hut this name, as

well as that by which it is now commonly called, was, and is,

often used indiscriminately in some localities for the Buzzards

and Harriers as well.

In former days the Kite, from the excellent sport it shewed

when pursued by Falcons, was esteemed a bird especially

adapted to the gratification of Royalty, and hv many

naturalists it is still called Milvus regalis, the epithet being

originally bestowed upon it from this circumstance. The

Falcons which cost Sir Thomas Monson so large a sum

of money, as previously mentioned (p. 51), were expressly

trained for this flight, hitherto unknown in England, and

the only ones he could ever get to perform it. That gentleman

was Master Falconer to James I., and, says the gossiping

chronicler, Sir Antony Weldon, “ in truth such a one, as no

Prince in Christendome had.” The birds killed nine Kites