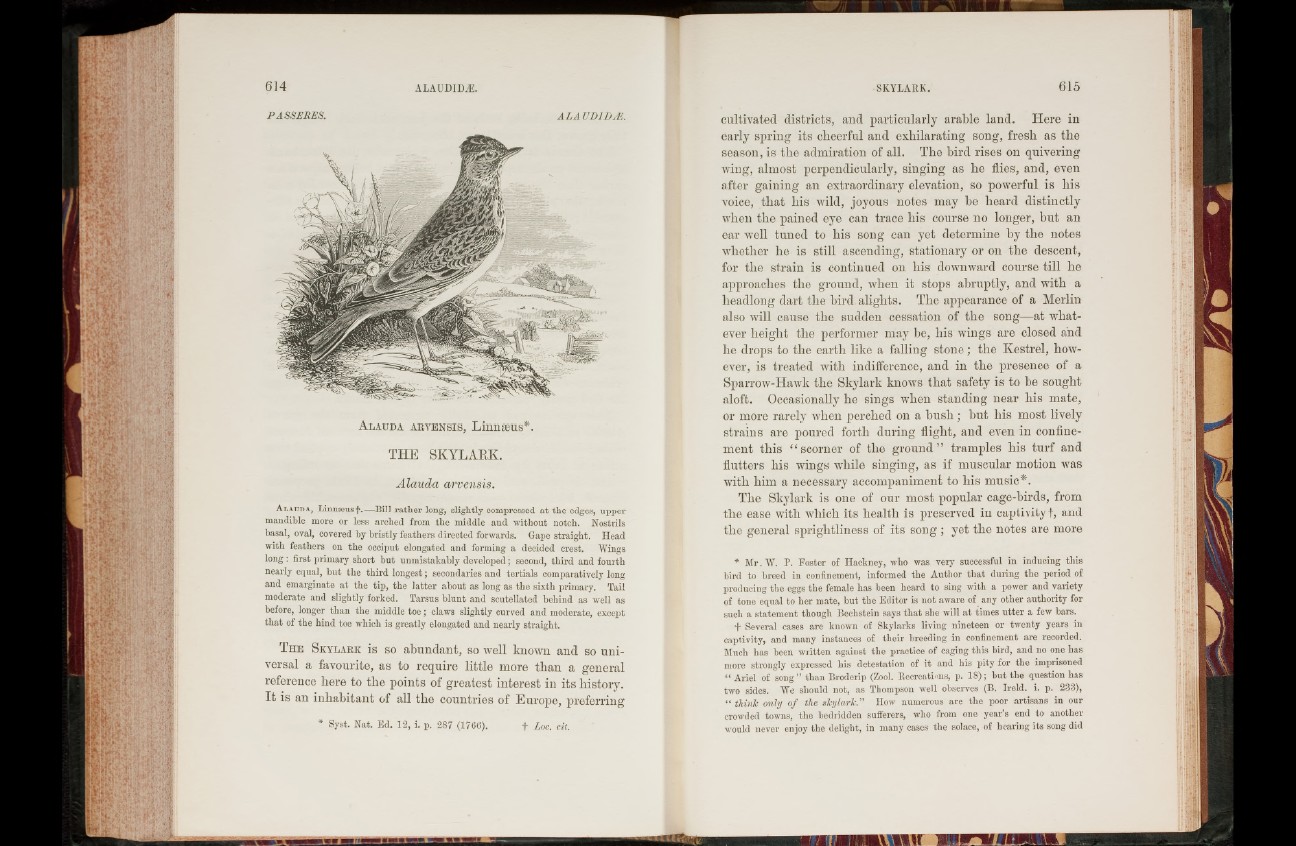

A la u d a ARVENSIS, L in n fflU S * .

THE SKYLARK.

Alauda arvensis.

A la ud a , Linnffiusf.—B ill rather long, slightly compressed at the edges, upper

mandible more or less arched from the middle and without notch. Nostrils

basal, oval, covered by bristly feathers directed forwards. Gape straight. Head

with feathers on the occiput elongated and forming a decided crest. Wings

long: first primary short but unmistakably developed; second, third and fourth

nearly equal, but the third longest; secondaries and tertials comparatively long

and emarginate at the tip, the latter about as long as the sixth primary. Tail

moderate and slightly forked. Tarsus blunt and scutellated behind as well as

before, longer than the middle to e ; claws slightly curved and moderate, except

that of the hind toe which is greatly elongated and nearly straight.

T h e S k y la rk is so abundant, so well known and so universal

a favourite, as to require little more than a general

reference here to the points of greatest interest in its history.

It is an inhabitant of all the countries of Europe, preferring

* Syst. Nat. Ed. 12, i . p. 287 (1766). + Loc. cit.

cultivated districts, and particularly arable land. Here in

early spring its cheerful and exhilarating song, fresh as the

season, is the admiration of all. The bird rises on quivering

wing, almost perpendicularly, singing as he flies, and, even

after gaining an extraordinary elevation, so powerful is his

voice, that his wild, joyous notes may be heard distinctly

when the pained eye can trace his course no longer, but an

ear well tuned to his song can yet determine by the notes

whether he is still ascending, stationary or on the descent,

for the strain is continued on his downward course till he

approaches the ground, when it stops abruptly, and with a

headlong dart the bird alights. The appearance of a Merlin

also will cause the sudden cessation of the song—at whatever

height the performer may be, his wings are closed and

he drops to the earth like a falling stone; the Kestrel, however,

is treated with indifference, and in the presence of a

Sparrow-Hawk the Skylark knows that safety is to be sought

aloft. Occasionally he sings when standing near his mate,

or more rarely when perched on a b u sh ; but his most lively

strains are poured forth during flight, and even in confinement

this “ seorner of the ground” tramples his turf and

flutters his wings while singing, as if muscular motion was

with him a necessary accompaniment to his music*.

The Skylark is one of our most popular cage-birds, from

the ease with which its health is preserved in captivity f, and

the general sprightliness of its song ; yet the notes are more

* Mr. W. P. Foster of Hackney, who was very successful in inducing this

bird to breed in confinement, informed the Author that during the period of

producing the eggs the female has been heard to sing with a power and variety

of tone equal to her mate, but the Editor is not aware of any other authority for

such a statement though Bechstein says that she will at times utter a few bars.

+ Several cases are known of Skylarks living nineteen or twenty years in

captivity, and many instances of their breeding in confinement are recorded.

Much has been written against the practice of caging this bird, and no one has

more strongly expressed his detestation of it and his pity for the imprisoned

“ Ariel of song” than Broderip (Zool. Recreations, p. 18); but the question has

two sides. We should not, as Thompson well observes (B. Ireld. i. p. 233),

“ think only o f the skylark.” How numerous are the poor artisans in our

crowded towns, the bedridden sufferers, who from one year’s end to another

would never enjoy the delight, in many cases the solace, of hearing its song did