is essential to their well-being, and in winter they eat snow. In avoiding

their enemies yak seem to rely chiefly on their. senseBf smell, which is

very acute ; their hearing and sight being apparently le^pkeen.

Beyond Ladak, where they are more or less^secure from persecution,

yak are far less wary. The large herds of cows and young bulls

wander over vast tracts of country, and in-summer make their appearance

on grassy plains which are deserted in winter. The-Solitary bu llsSn the

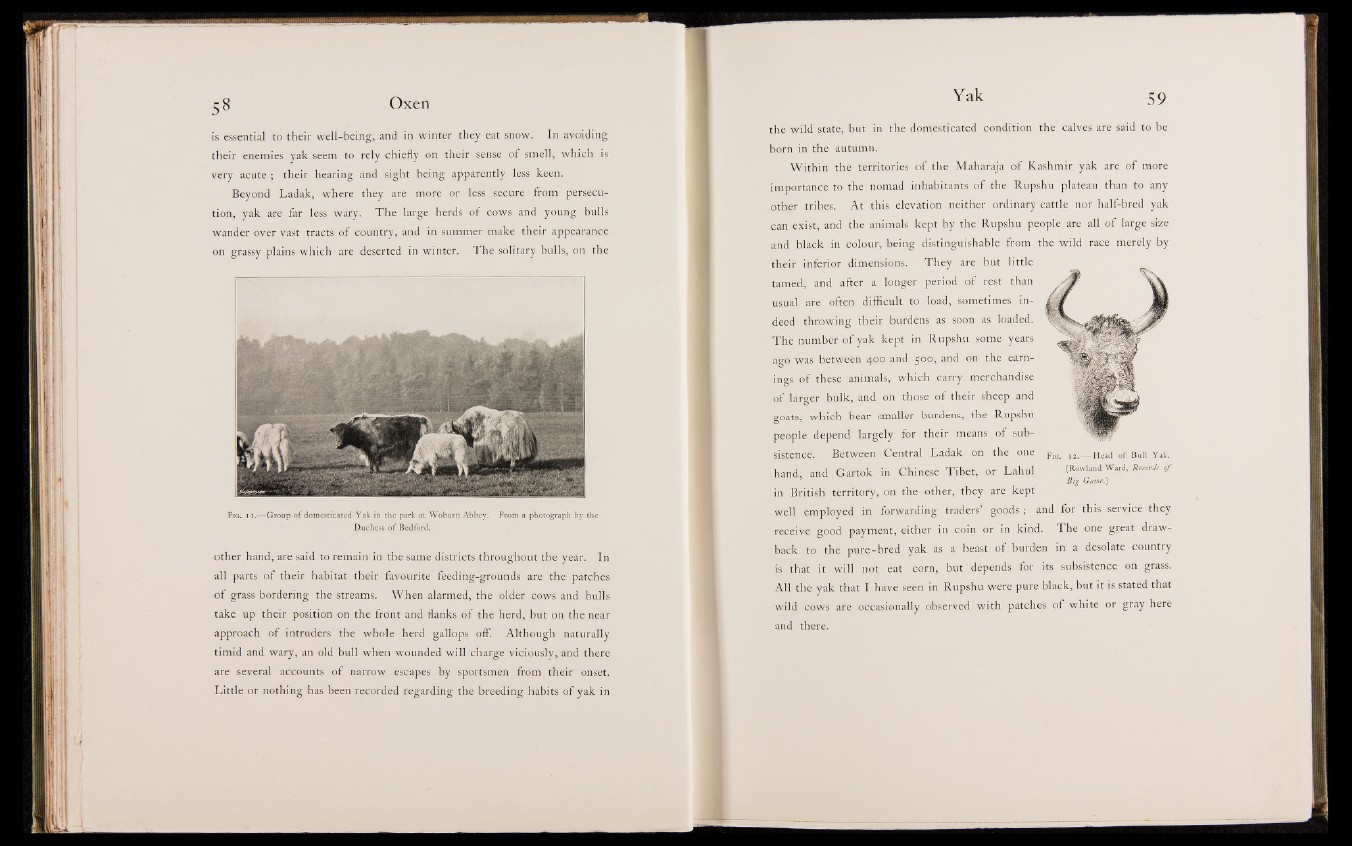

F ig. II .—Group of domesticated Yak in the park at Woburn Abbey. From a photograph by the

Duchess of Bedford.

other hand, are said to remain in the same districts throughout the-year. In

all parts of their habitat their favourite feeding-grounds are the patches

of grass bordering the streams. When alarmed, the older cows and bulls

take up their position on the front and flanks ift the herd, but on the near

approach of intruders the whole herd gallops off! Although naturally

timid and wary, an old bull when wounded will charge viciously, and there

are several accounts of narrow escapes by sportsmen from their onset.

Little or nothing has been recorded regarding the breeding habits of yak in

the wild state, but in the domesticated condition the calves are said to be

born in the autumn.

Within the territories of the Maharaja of Kashmir yak are of more

importance to the nomad inhabitants of the Rupshu plateau than to any

other tribes. At this elevation neither ordinary cattle nor half-bred yak

can exist, and the animals kept by the Rupshu people are all of large size

and black in colour, being distinguishable from the wild race merely by

their inferior dimensions. They are but little

tamed, and after a longer period of rest than

usual are often difficult to load„Jpmetimes indeed

throwing their burdens as soon as loaded.

The number of yak kept in R upshu some years

ago was between 4<H and 506, and on the earn-

ingBhf these; animals, which carry merchandise

of larger bulk, and on those of their sheep aid

jgpats, which bear smaller burdens, the Rupshu

people depend la rg e ly :S r their means of sub-

gstence. Between Central Ladakftn the .one

hand, and Gartok in Chinese Tibet, or Lahul

in British territory, on thefljther, they are kept

well employed in forwarding traders1 goods ; and foSthis service they

receive good payment, either in coin or in kind. The one great drawback

(Rowland Ward, Records o f

Big Game.)

t§i.;the pure-bred yak as a beast of burden in a desolate country

is that it will not eat corn, but depends for its subsistence on grass.

All the yak that I have seen in Rupshu were pure black, but it is stated that

wild cows are occasionally observed with patches of white or gray here

and there.