1 2 Oxen

travelled frequently in Poland, and the figures of the two animals may be

regarded as having been executed under his own immediate supervision.

It has indeed been urged that the portrait of the aurochs is that of a

domestic bullock, but Messrs. Nehring and Schiemenz have conclusively

shown that this is not the case, and that the original the picture was a

wild Polish aurochs. In Herberstain’s time, that is to say at least as late

as the middle of the sixteenth century, the aurochs was preserved in a

single Polish forest, as is the bison at the present day in another. The

forest in question is that of Jaktorowka, situated about fifty-five kilometres

to the west-south-west of Warsaw in the districts of Bolemow and

Sochaczew. Other evidence is to the effect that the last survivor of the

herd in this forest was slain in the year 1 627. Regarding its survival in

other districts, a skull preserved for centuries in the castle of Bromberg,

Prussia, which shows three spear-wounds on the forehead, is - stated to

afford decisive evidence that the auroeh(lived- on in that part o f the

country at least as late as the twelfth os thirteenth century. It is further

evident that, like its cousin the bison, the aurochs was a forest-dwelling

animal.

Such being the case, it may be taken as practically certain that several

of the breeds of European cattle are the immediate descendants of the

aurochs. Calves of the latter were probably caught and tamed by the early

inhabitants of Europe, and their-progeny gave birth to some at least of the

present European breeds, for which there is accordingly no need to seek

an Eastern origin. That the domesticated breed would become smaller

than the wild ancestral race is only what might naturally be expected ; a

precisely analogous instance occurring in the yak, of which the race

domesticated in the Bhutan and Darjiling districts bear no comparison to

the wild animal, or even to the semi-domesticated breed kept bv the

nomads of the Rupshu plateau.

Although otherwise white, the half-wild Chillingham cattle usually

Aurochs * 3

have the muzzle and the inside of the ears reddish, whereas in the Cadzow

breed the same parts are black. In other European breeds various shades

of dun, fawn, and red, as well as black, are commonly met with ; and as

red or fawn is a lessgjjpecialised type o f coloration than black, it might

well have been thought that one of these was the predominant tint of

the aurochs. According, however, to the authors already referred to,

Herberstain’s woodcut and another ancient picture show that the ancient

wild ox of Europe was black. I f this is to be depended on, the reds and

duns of our domesticated breeds must apparently be regarded as a reversion

to the coloration of some older race.

Like the bison, the aurochilis known to have been common in the

Black Forest in the time of Julius Cassar ; and was of course still more

widely spread in earlier years. In Britain its remains, as already mentioned,

occur in deposits as late a;s thoseijf the fen districts, but none have hitherto

been identified in those dating from orgibsequent to the time of the

Roman occupation, when it would accordingly appear to have become

exterminated in England.

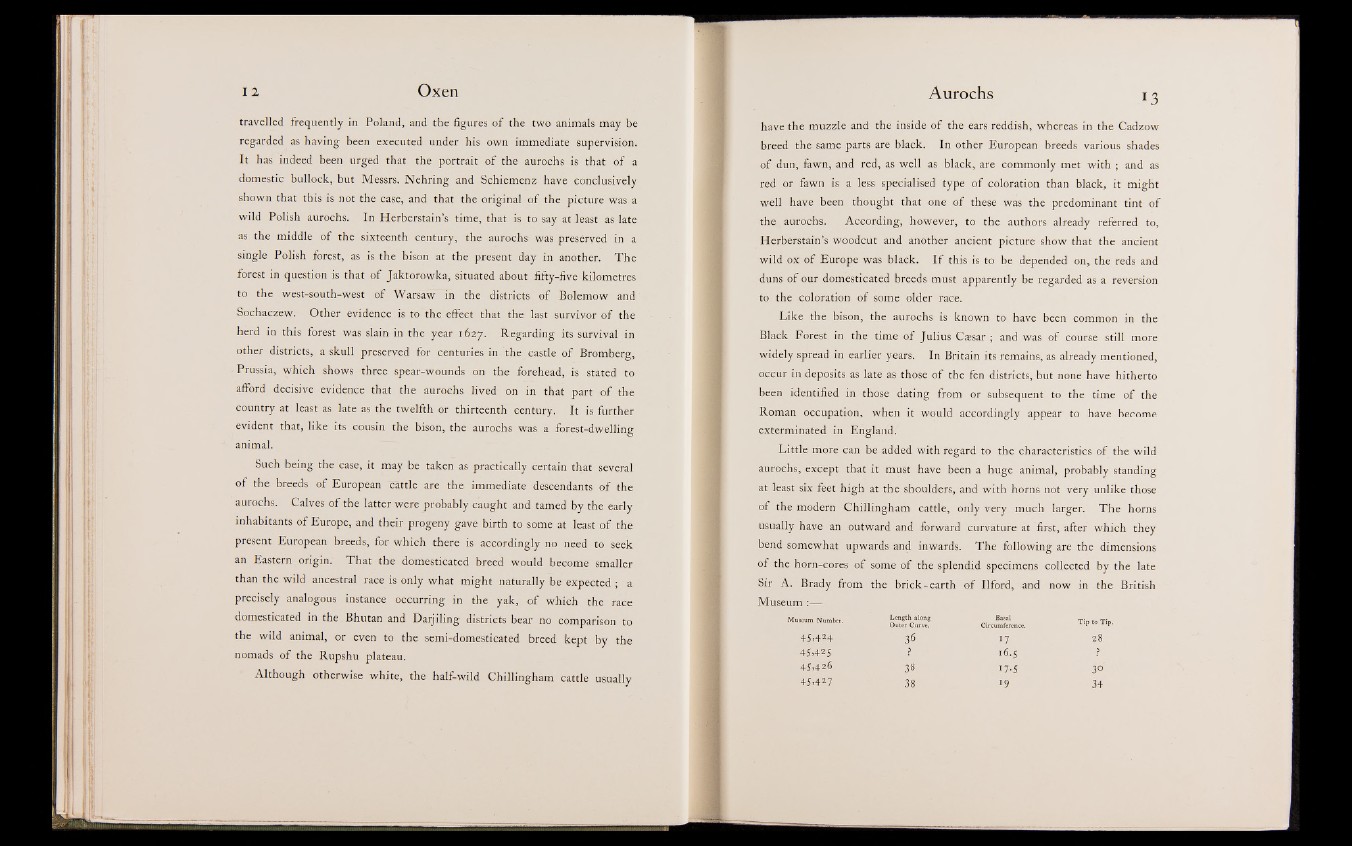

Little more can be added with regard to the characteristics ojf&the wild

aurochs, except that it must have been a huge animal, probably standing

at least six feet high at the shouldfjSsj and with horns not very unlike those

of the modern Chillingham cattle, only very much larger. The horns

usually have anButward and forwardl|eurvature at first, after which they

bend somewhat upwards and inwards. The following are the dimensions

of the horn-cores o f some of the splendid specimens collected by the late

Sir A. Brady from the brick-earth of Ilford, and now in the British

Museum

Museum Number. Length along

Outer Curve. Circumference. Tip to Tip.

4 5 . 4 M 3 6 1 7 2 8

4 5 . 4 2 5 . ? ?

1 6 , 5

4 5 , 4 2 6

H - 5 3 ° '

4 5 . 4 2 7 3 8 H 3 4