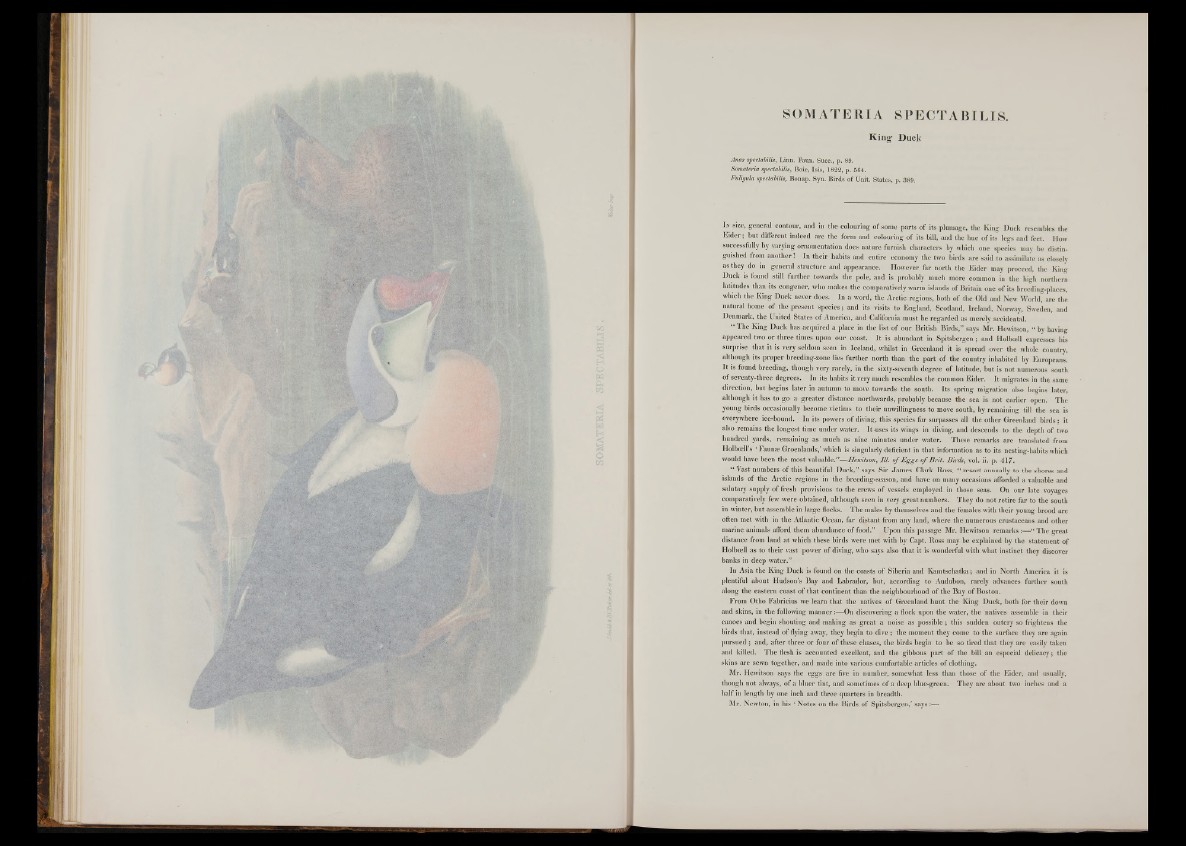

SOMATERIA SPECTABILIS.

King' Duck

Anas spectabilis, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 89.

Somateria spectabilis, Boie, Isis, 1822, p. 564.

Fuligula spectabilis, Bonap. Syn. Birds of Unit. States, p. 389.

In size, general contour, and in the colouring of some parts o f its plumage, the King Duck resembles the

Eider; but different indeed are the form and colouring o f its bill, and the hue of its legs and feet. How

successfully by varying ornamentation does nature furnish characters by which one species may be distinguished

from another! In their habits and entire economy the two birds are said to assimilate as closely

as they do in general structure and appearance. However far north the Eider may proceed, the King

Duck is found still further towards the pole, and is probably much more common in the high northern

latitudes than its congener, who makes the comparatively warm islands of Britain one of its breeding-places,

which the King Duck never does. In a word, the Arctic regions, both of the Old and New World, are the

natural home of the present species; and its visits to England, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, and

Denmark, the United States o f America, and California must be regarded as merely accidental.

“ The King Duck has acquired a place in the list o f our British Birds,” says Mr. Hewitson, “ by having

appeared two or three times upon our coast, It is abundant in Spitsbergen ; and Holboell expresses his

surprise that it is very seldom seen in Iceland, whilst in Greenland it is spread over the whole country,

although its proper breeding-zone lies further north than the part of the country inhabited by Europeans.

It is found breeding, though very rarely, in the sixty-seventh degree o f latitude, but is not numerous south

o f seventy-three degrees. In its habits it very much resembles the common Eider. It migrates in the same

direction, but begins later in autumn to move towards the south. Its spring migration also begins later,

although it has to go a greater distance northwards, probably because the sea is not earlier open. The

young birds occasionally become victims to their unwillingness to move south, by remaining till the sea is

everywhere ice-bound. In its powers o f diving, this species far surpasses all the other Greenland birds; it

also remains the longest time under water. It-uses its wings in diving, and descends to the depth of two

hundred yards, remaining as much as nine minutes under water. These remarks are translated from

Holboell’s ‘ Faunas Groenlauds,’ which is singularly deficient in that information as to its ncsting-habits which

would have been the most valuable.”—Hewitson, III. o f E g g s o f Brit. Birds, vol. ii. p. 417.

“ Vast numbers of this beautiful Duck,” says Sir James Clark Ross, “ resort annually to the shores and

islands of the Arctic regions in the breeding-season, and have on many occasions afforded a valuable and

salutary supply o f fresh provisions to the crews of vessels employed in those seas. On our late voyages

comparatively few were obtained, although seen in very great numbers. They do not retire far to the south

in winter, but assemble in large flocks. The males by themselves and the females with their young brood are

often met with in the Atlantic Ocean, far distant from any land, where the numerous crustaceans and other

marine animals afford them abundance o f food.” Upon this passage Mr. Hewitson remarks The great

distance from land at which these birds were met with by Capt. Ross may be explained by the statement o f

Holboell as to their vast power o f diving, who says also that it is wonderful with what instinct they discover

banks in deep water.”

In Asia the King Duck is found on the coasts of Siberia and Kamtschatka; and in North America it is

plentiful about Hudson’s Bay and Labrador, but, according to Audubon, rarely advances further south

along the eastern coast o f that continent than the neighbourhood o f the Bay o f Boston.

From Otho Fabricius we learn that the natives o f Greenland hunt the King Duck, both for their down

and skins, in the following manner:— On discovering a flock upon the water, the natives assemble in their

canoes and begin shouting and making as great a noise as possible; this sudden outcry so frightens the

birds that, instead o f flying away, they begin to dive; the moment they come to the surface they are again

pursued ; and, after three or four o f these chases, the birds begin to be so tired that they are easily taken

and killed. The flesh is accounted excellent, and the gibbous part o f the bill an especial delicacy; the

skins are sewn together, and made into various comfortable articles o f clothing.

Mr. Hewitson says the eggs are five in number, somewhat less than those o f the Eider* and usually,

though not always, o f a bluer tint, and sometimes of a deep blue-green. They are about two inches and a

half in length by one inch and three quarters in breadth.

Mr. Newton, in his ‘Notes on the Birds of Spitsbergen,’ says:—