Black Tern.

Sterna fissipes, et navia, Linn. Syst. Nat. (1766), tom. i. p. 228.

nigra, Briss. Orn. (1760), tom. vi. p. 211.

plumbea, Wils. Am. Orn., vol. vii. 1831, pi. lx., young.

Hydrochelidon nigra, Boie, Isis, 1822, p. 563.

---------------— nigricans, Brehm, Vög. Deutschl., p.. 794.

----------------- obscura, Brehm, ibid., p. 795.

----------------- fissipes, G. R. Gray, Gen. of Birds, vol. iii. p. 660, Hydrochelidon, sp. 5.

------------- plumbea, Lawr. Gen. Rep. 1858, p. 864.

Viralva nigra, Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiii. p. 167.

The generic term Hydrochelidon was instituted by Boie for a small section o f the Sternidce possessing certain

peculiarities o f structure accompanied by an equally peculiar style o f colouring, and whose habits and economy

are unlike those o f the other members o f their family, from which they also differ in the kind of situations

they frequent. The ordinary Terns or Sea-Swallows, genus Hirwido, are true sea-birds, which either retire

to shingly beaches or ascend the larger rivers with banks of a similar character for the purpose o f breeding,

incubate their two eggs on the bare ground, fly with a laboured flapping motion o f their wings, and descend

upon their piscine food with a perpendicular stoop like that of the Kingfisher. The members o f the genus

Hydrochelidon, on the other hand, frequent the inland fresh waters (lakes and rivers) rather than the open

sea, feed principally upon large winged insects, which they take in the air, and deposit three or four eggs

in a nest o f weeds placed in a tuft of grass in the midst of reed-beds. The true sea-Terns have short webbed

feet, while the feet o f the marsh-Terns, as the birds o f the present form are called, are more lengthened and

have the interdigital membrane but little developed. The Black Tern, which is a migrant, comes to us in the

spring from a warmer climate, and, if any suitable locality be left in which it may remain unmolested, will

reproduce its kind during its stay. On this point Mr. Stevenson, o f Norwich, writes to me —“ Although

this species formerly nested in considerable numbers, both on our eastern broads and in the fens o f the

western part o f Norfolk, it has almost ceased to breed in the county. I know o f but one or two solitary

instances o f a pair remaining to breed with us during the last few years ; Mr. Newton informs me that in the

spring o f 1852, owing to the extent of land then under water from the immense floods o f the previous winter,

two or three pairs bred in Feltwell fen, where they had not been known to remain for some years. Draining,

and the abominable system of indiscriminate egging, are the principal causes why this bird, the Black-tailed

Godwit, and other species now proceed further north. The old birds regularly appear on the coast every

spring during the months o f April and May, and again with their young in autumn (August, September,

and October). The Black Tern is said to have formerly bred at Winterton, near Yarmouth ; and Lubbock,

in a communication to Yarrell, says ‘ the great breeding-place, in a wet alder-carr at Upton, where, twenty

years hack, hundreds upon hundreds o f nests might be found at the end o f May, has been broken up some

years.” ’

During the numerous visits I have made to the middle portion o f our beautiful Thames in the month of

May, for the last forty years, I have seldom missed seeing the Black Tern hawking over the reaches in

the neighbourhood of Maidenhead, Cookham, and Marlow. At that season they are apparently passing over

our island from the Bristol Channel to some eastward localities, and they merely stay for a few hours, in

their course down the river, one day at Henley, the next at Maidenhead or Wiudsor, thence proceeding to

the Nore and other parts o f the eastern coast. From the 10th to the 19th o f May, 1866, several solitary

individuals passed my boat; and a similar occurrence took place in the same locality the succeeding year.

Occasionally I have seen the Common Tern, the Arctic Tern, and the present species in the same reach at

one time; an example of each o f the three species, all o f which fell to my own gun in 1866, may be seen

at Taplow Court, Mr. C. Pascoe Grenfell having kindly accepted them as a memento of these birds occasionally

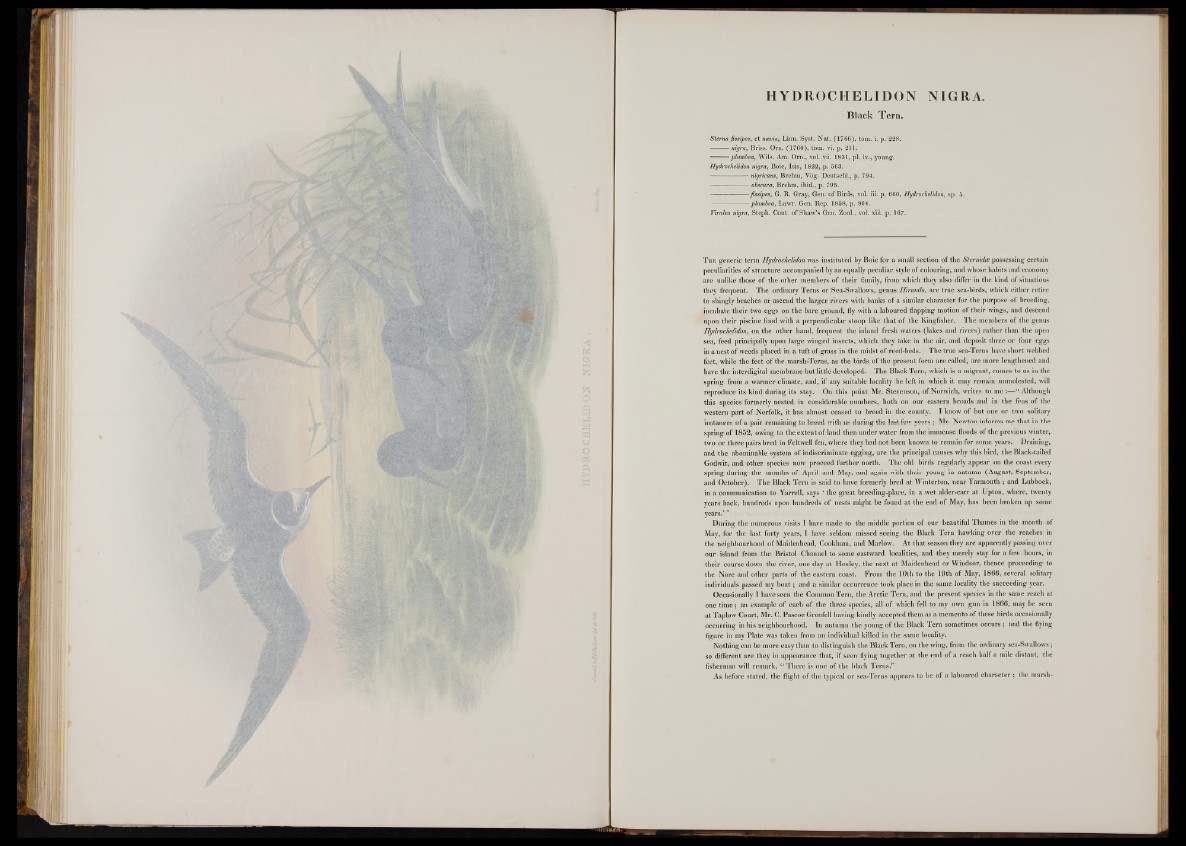

occurring in his neighbourhood. In autumn the young o f the Black Tern sometimes occurs; and the flying

figure in my Plate was taken from an individual killed in the same locality.

Nothing can be more easy than to distinguish the Black Tern, on the wing, from the ordinary sea-Swallows;

so different are they in appearance that, if seen flying together at the end o f a reach half a mile distant, the

fisherman will remark, “ There is one of the black Terns.”

As before stated, the flight o f the typical or sea-Terns appears to be of a laboured character ; the marsh