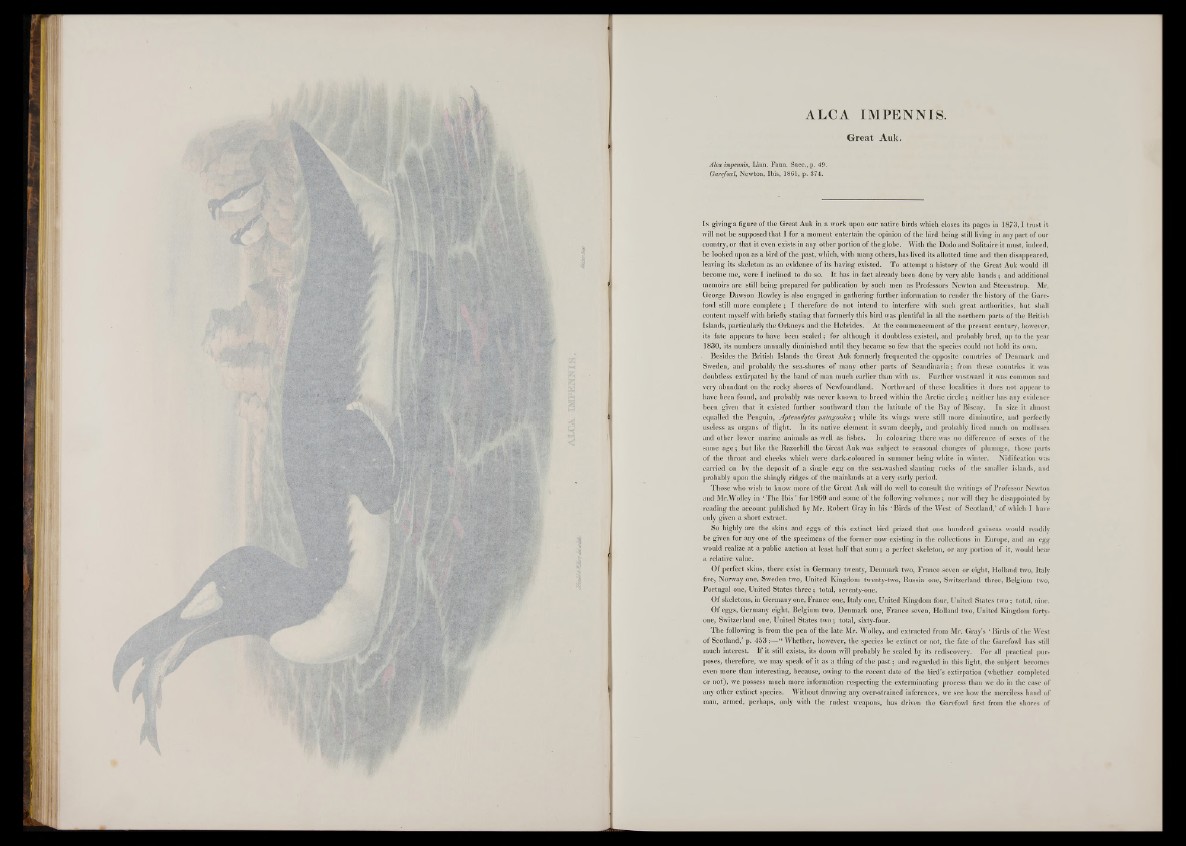

G re a t Auk.

Alca impennis, Linn. Faun. Suec.,p. 49.

Garefowl, Newton, Ibis, 1861, p. 374.

In giving a figure o f the Great Auk in a work upon our native birds which closes its pages in 1873,1 trust it

will not be supposed that I for a moment entertain the opinion o f the bird being still living in any part o f our

country, or that it even exists in any other portion o f the globe. With the Dodo and Solitaire it must, indeed,

be looked upon as a bird o f the past, which, with many others, has lived its allotted time and then disappeared,

leaving its skeleton as an evidence of its having existed. To attempt a history of the Great Auk would ill

; I inclined to do so. It has in fact already been done by very able hands ; and additional

i still being prepared for publication by such men as Professors Newton and Steenstrup. Mr.

George Dawson Rowley is also engaged in gathering further information to render the history of the Garefowl

still more complete; I therefore do not intend to interfere with such great authorities, but shall

content myself with briefly stating that formerly this bird was plentiful in all the northern parts o f the British

Islands, particularly the Orkneys and the Hebrides. At the commencement o f the present century, however,

its fate appears to have been sealed; for although it doubtless existed, and probably bred, up to the year

1830, its numbers annually diminished until they became so few that the species could not hold its own.

Besides the British Islands the Great Auk formerly frequented the opposite countries of Denmark and

Sweden, and probably the sea-shores o f many other parts o f Scandinavia; from these countries it was

doubtless extirpated by the hand o f man much earlier than with us. Further westward it was common and

very abundant on the rocky shores of Newfoundland. Northward o f these localities it does not appear to

have been found, and. probably was never known to breed within the Arctic circle; neither has any evidence

been given that it existed further southward than the latitude o f the Bay o f Biscay. In size it almost

equalled the Penguin, Aptenodytes patagónica; while its wings were still more diminutive, and perfectly

useless as organs o f flight. In its native element it swam deeply, and probably lived much on mollusca

and other lower marine animals as well as fishes. In colouring there was no difference of sexes of the

same a g e ; but like the Razorbill the Great Auk was subject to seasonal changes of plumage, those parts

o f the throat and cheeks which were dark-coloured in summer being white in winter. Nidification was

carried on by the deposit o f a single egg on the sea-washed slanting rocks o f the smaller islands, and

probably upon the shingly ridges of the mainlands at a very early period.

Those who wish to know more o f the Great Auk will do well to consult the writings o f Professor Newton

and Mr.Wolley in ‘ The Ibis ’ for 1860 and some of the following volumes; nor will they be disappointed by

reading the account published by Mr. Robert Gray in his ‘ Birds of the West of Scotland,’ of which I have

only given a short extract.

So highly are the skins and eggs o f this extinct bird prized that one hundred guineas would readily

be given for any one o f the specimens o f the former now existing in the collections in Europe, and an egg

would realize at a public auction at least half that sum ; a perfect skeleton, or any portion o f it, would hear

a relative value.

O f perfect skins, there exist in Germany twenty, Denmark two, France seven or eight, Holland two, Italy

five, Norway one, Sweden two, United Kingdom twenty-two, Russia one, Switzerland three, Belgium two,

Portugal one, United States three; total, seventy-one.

Of skeletons, in Germany one, France one, Italy one, United Kingdom four, United States two; total, nine.

Of eggs, Germany eight, Belgium two, Denmark one, France seven, Holland two, United Kingdom forty-

one, Switzerland one, United States two; total, sixty-four.

The following is from the pen o f the late Mr. Wolley, and extracted from Mr. Gray’s ‘ Birds o f the West

of Scotland,’ p. 4 5 3 :— “ Whether, however, the species be extinct or not, the fate of the Garefowl has still

much interest. If it still exists, its doom will probably be sealed by its rediscovery. For all practical purposes,

therefore, we may speak o f it as a thing o f the past; and regarded in this light, the subject becomes

even more than interesting, because, owing to the recent date o f the bird’s extirpation (whether completed

or not), we possess much more information respecting the exterminating process than we do in the case of

any other extinct species. Without drawing any over-strained inferences, we see how the merciless hand o f

man, armed, perhaps, only with the rudest weapons, has driven the Garefowl first from the shores of