ANAS BO SC HAS, Linn.

Mallard or Wild Duck.

Anas boschas, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 46.

*7^— adunca, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 206.

——/era, Leach, Syst. .Cat. of Indig. Mamm. and Birds in Brit. Mus., p. 39.

archiboschas, subboschas, et conboschas, Brehm, Yog. Deutschl., pp. 862, 864, 865, tab. xlii. fig. 2.

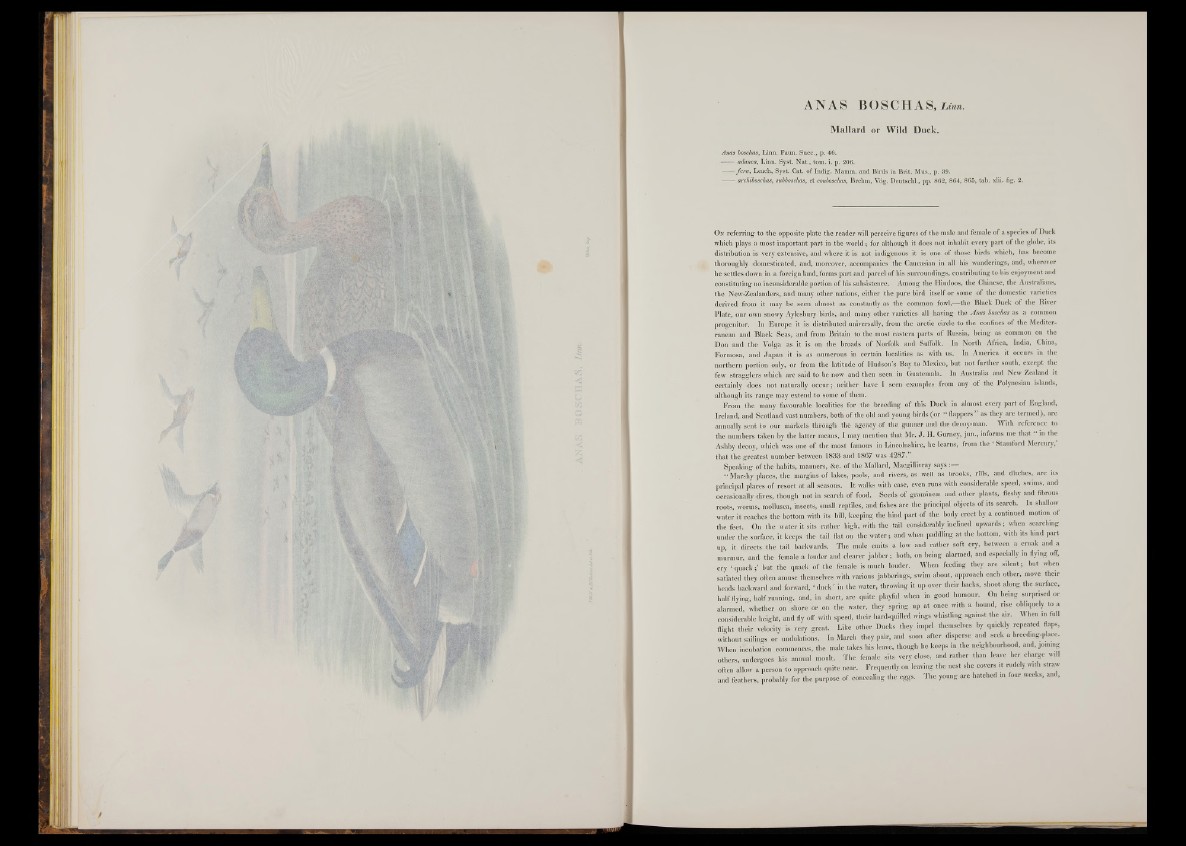

On referring to the opposite plate the reader will perceive figures of the male and female o f a species o f Duck

which plays a most important part in the world; for although it does not inhabit every part o f the globe, its

distribution is very extensive, and where it is not indigenous it is one of those birds which, has become

thoroughly domesticated, and, moreover, accompanies the Caucasian in all his wanderings, and, wherever

he settles down in a foreign land, forms part and parcel of his surroundings, contributing to bis enjoyment and

constituting no inconsiderable portion of his subsistence. Among the Hindoos, the Chinese, the Australians,

the New-Zealanders, and many other nations, either the pure bird itself or some of the domestic varieties

derived from it may be seen almost as constantly as the common fowl,— the Black Duck of the River

Plate, our own snowy Aylesbury birds, and many other varieties all having the Anas boschas as a common

progenitor. In Europe it is distributed universally, from the arctic circle to the confines of the Mediterranean

and Black Seas, and from Britain to the most eastern parts o f Russia, being as common on the

Don and the Volga as it is on the broads of Norfolk and Suffolk. In North Africa, India, China,

Formosa, and Japan it is as numerous in certain localities as with us. In America it occurs in the

northern portion only, or from the latitude of Hudson’s Bay to Mexico, but not further south, except the

few stragglers which are said to he now and then seen in Guatemala. In Australia and New Zealand it

certainly does not naturally occur; neither have I seen examples from any of the Polynesian islands,

although its range may extend to some o f them.

From the many favourable localities for the breeding of this Duck in almost every part o f England,

Ireland, and Scotland vast numbers, both of the old and young birds (or “ flappers as they are termed), are

annually sent to our markets through the agency of the gunner and the decoy-man. With reference to

the numbers taken by the latter means, I may mention that Mr. J. H. Gurney, jun., informs me that “ in the

Ashby decoy, which was one of the most famous in Lincolnshire, he learns, from the ‘ Stamford Mercury,

that the greatest number between 1833 and 1867 was 4287.”

Speaking of the habits, maimers, &c. of the Mallard, Macgillivray says :

“ Marshy places, the margins of lakes, pools, and rivers, as well as brooks, rills, and ditches, are its

principal places o f resort at all seasons. It walks with ease, even runs with considerable speed, swims, and

occasionally dives, though not in search of food. Seeds o f gramine® and other plants, fleshy and fibrous

roots, worms, mollusca, insects, small reptiles, and fishes are the principal objects o f its search. In shallow

water it reaches the bottom with its bill, keeping the hind part o f the body erect by a continued motion of

the feet. On the water it sits rather high, with the tail considerably inclined upwards; when searching

under the surface, it keeps the tail flat on the water; and when paddling at the bottom, with its hind part

up, it directs the tail backwards. The male emits a low and rather soft cry, between a croak and a

murmur, and the female a louder and clearer jabber; both, on being alarmed, and especially in flying off,

cry ‘ quack;’ but the quack of the female is much louder. When feeding they are silent; but when

satiated they often amuse themselves with various jabberings, swim about, approach each other, move their

heads backward and forward, ‘ duck ’ in the water, throwing it up over their backs, shoot along the surface,

half flying, half running, and, in short, are quite playful when in good humour. On being surprised or

alarmed, whether on shore or on the water, they spring up at once with a bound, rise obliquely to a

considerable height, and fly off with speed, their hard-quilled wings whistling against the air. When in full

flight their velocity is very great. Like other Ducks they impel themselves by quickly repeated flaps,

without sailings or undulations. In March they pair, and soon after disperse and seek a breedmg-place.

When incubation commences, the male takes his leave, though he keeps in the neighbourhood, and, joining

others, undergoes his annual moult. The female sits very close, and rather than leave her charge will

often allow a person to approach quite near. Frequently on leaving the nest she covers it rudely with straw

and feathers, probably for the purpose of concealing the eggs. The young are hatched in four weeks, and,