Crested Cormorant, or Shag.

Pelecanus graculus, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 217.

cristatus, Fab. Faun. Groenl., p. 90.

Carlo cristatus, Temm. Man. d’Orn., 2nd edit., tom. ii. p. 900, tom. iv. p. 565.

Halieus graculus, Licht. Verz. der Doubl, des zool. Mus. zu Berlin, p. 86.

Phalacrocorax graculus, Leach, Syst. Cat. of Indig. Mamm. and Birds in Brit. Mus., p. 34.

Hydrocorax graculus, Vieill. Nouv. Diet. d’Hist. Nat., torn. viii. p. 87.

Carlo graculus, Meyer, Taschenb. deutsch. Vög., torn. ii. p. 578.

Phalacrocorax cristatus, Stepb. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiii. p. 83.

Pelecanus leucogaster, Vieill. Nouv. Diet. d’Hist. Nat., 2nd edit., tom. viii. p. 90.

Carlo Irachyurus, Brehm, Vög. Deutschi., p. 822.

Graculus IAnncei, Gray and Mitch. Gen. of Birds, vol. iii. p. 667, Graculus, sp. 6.

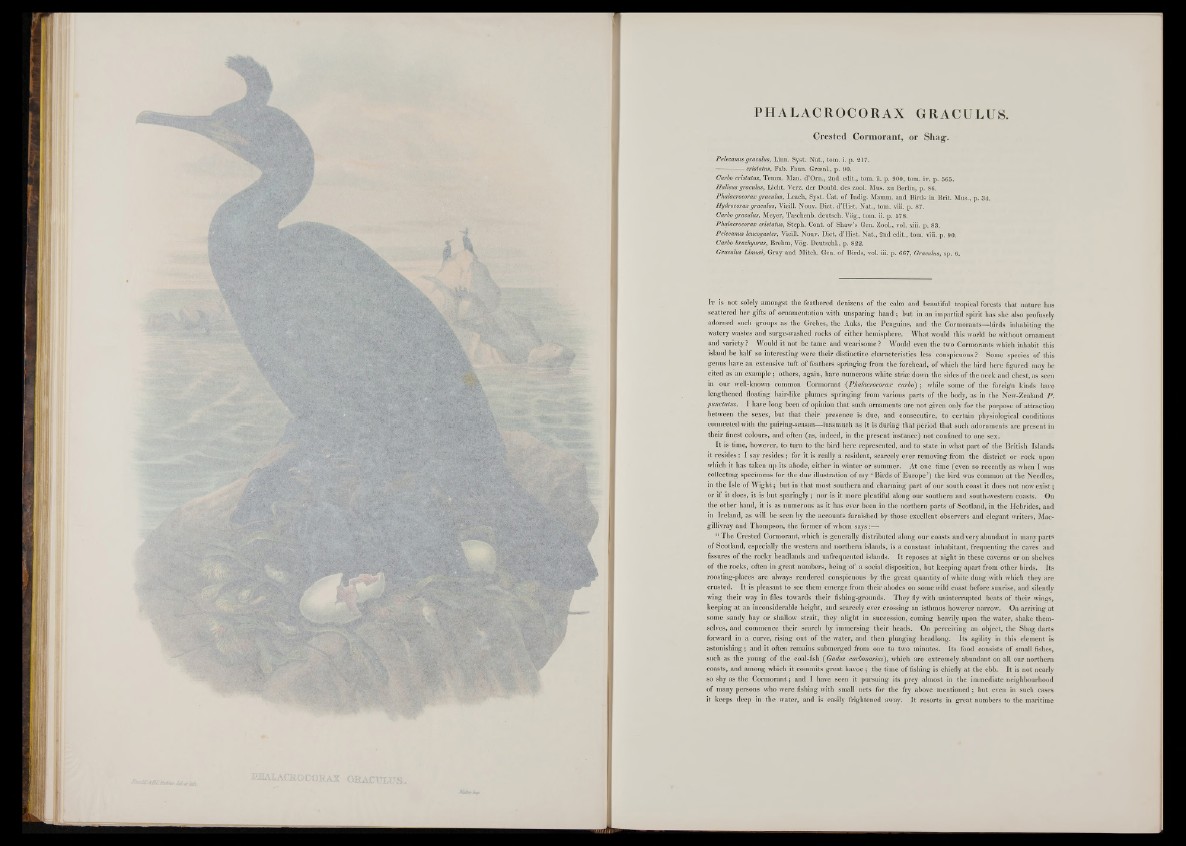

It is not solely amongst the feathered denizens o f the calm and beautiful tropical forests that nature has

scattered her gifts o f ornamentation with unsparing hand ; but in an impartial spirit has she also profusely

adorned such groups as the Grebes, the Auks, the Penguins, and the Cormorants— birds inhabiting the

watery wastes and surge-washed rocks o f either hemisphere. What would this world be without ornament

and variety ? Would it not be tame and wearisome ? Would even the two Cormorants which inhabit this

island be half so interesting were their distinctive characteristics less conspicuous ? Some species o f this

genus have an extensive tuft o f feathers springing from the forehead, of which the bird here figured may be

cited as an example; others, again, have numerous white striae down the sides o f the neck and chest, as seen

in our well-known common Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carlo) ; while some o f the foreign kinds have

lengthened floating hair-like plumes springing from various parts o f the body, as in the New-Zealand P .

punctatus. I have long been o f opinion that such ornaments are not given only for the purpose of attraction

between the sexes, but that their presence is due, and consecutive, to certain physiological conditions

connected with the pairing-season—inasmuch as it is during that period that such adornments are present in

their finest colours, and often (as, indeed, in the present instance) not confined to one sex.

It is time, however, to turn to the bird here represented, and to state in what part o f the British Islands

it resides: I say resides; for it is really a resident, scarcely ever removing from the district or rock upon

which it has taken up its abode, either in winter or summer. At one time (even so recently as when I was

collecting specimens for the due illustration o f my ‘ Birds of Europe’) the bird was common at the Needles,

in the Isle o f Wight; but in that most southern and charming part o f our south coast it does not now exist;

or if it does, it is but sparingly ; nor is it more plentiful along our southern and south-western coasts. On

the other hand, it is as numerous as it has ever been in the northern parts o f Scotland, in the Hebrides, and

in Ireland, as will be seen by the accounts furnished by those excellent observers and elegant writers, Mac-

gillivray and Thompson, the former o f whom says:—

“ The Crested Cormorant, which is generally distributed along our coasts and very abundant in many parts

o f Scotland, especially the western and northern islands, is a constant inhabitant, frequenting the caves and

fissures o f the rocky headlands and unfrequented islands. It reposes at night in these caverns or on shelves

o f the rocks, often in great numbers, being of a social disposition, but keeping apart from other birds. Its

roosting-places are always rendered conspicuous by the great quantity o f white dung with which they are

crusted. It is pleasant to see them emerge from their abodes on some wild coast before sunrise, and silently

wing their way in files towards their fishing-grounds. They fly with uninterrupted beats o f their wings,

keeping at an inconsiderable height, and scarcely ever crossing an isthmus however narrow. On arriving at

some sandy bay or shallow strait, they alight in succession, coming heavily upon the water, shake themselves,

and commence their search by immersing their heads. On perceiving an object, the Shag darts

forward in a curve, rising out o f the water, and then plunging headlong. Its agility in this element is

astonishing; and it often remains submerged from one to two minutes. Its food consists o f small fishes,

such as the young o f the coal-fish ( Gadus carlonarius), which are extremely abundant on all our northern

coasts, and among which it commits great havoc; the time o f fishing is chiefly at the ebb. It is not nearly

so shy as the Cormorant; and I have seen it pursuing its prey almost in the immediate neighbourhood

o f many persons who were fishing with small nets for the fry above mentioned; but even in such cases

it keeps deep in the water, and is easily frightened away. It resorts in great numbers to the maritime