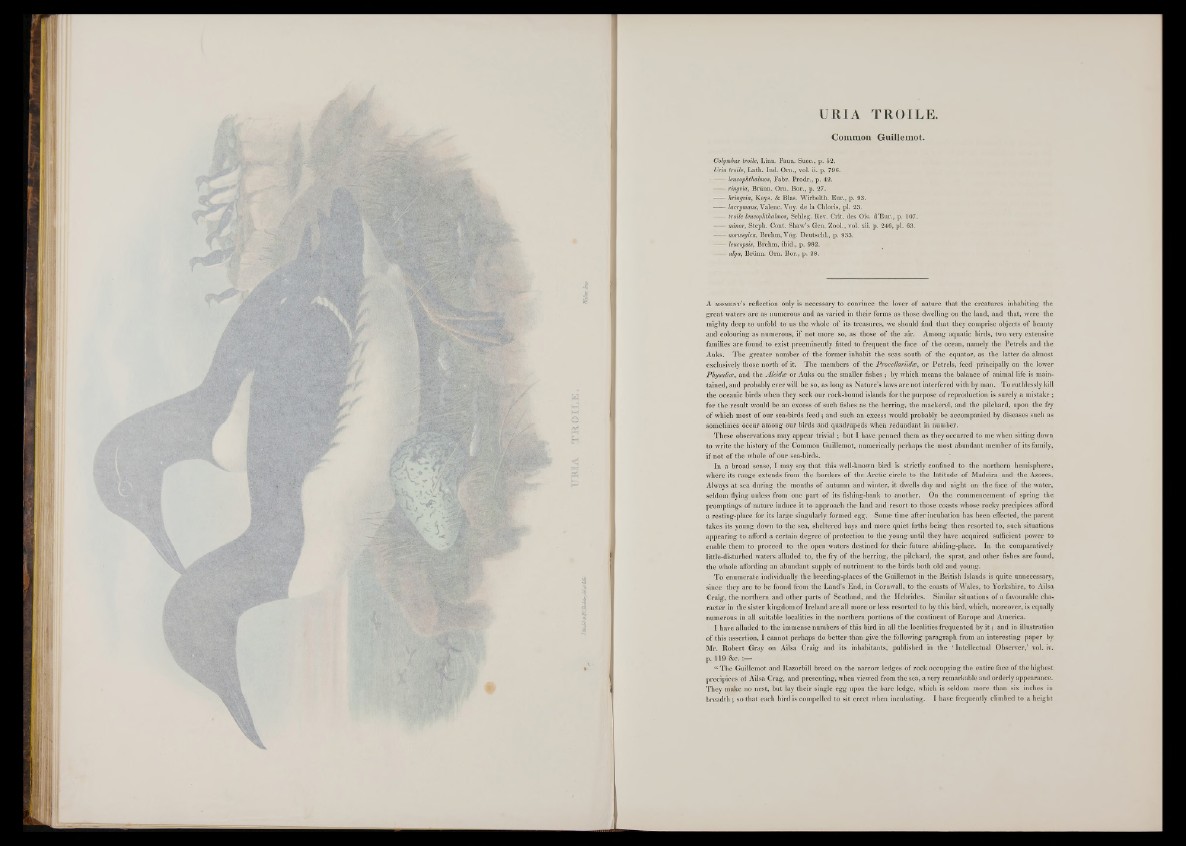

Common Guillemot.

Colymbus troile, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 52.

Uria troile, Lath. Ind. Om., voi. ii. p. 796.

leucophthahnos, Fabr. Prodr., p. 42.

— ringvia, Brünn. Om. Bor., p. 27.

hringvia, Keys. & Blas. Wirbelth. Eur., p. 93.

■k* lacrymans,Valene. Yoy. de la Cbloris, pi. 23.

— troile leucophthalmos, Schleg. Rev. Crit. des Ois. d’Eur., p. 107.

— minor, Steph. Cont. Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiì. p. 246, pi. 63.

— norwegica, Brehm, Vög. Deutsch!., p. 933.

— leucopsìs, Brehm, ibid., p. 982.

— alga, BrUnn. Om. Bor., p. 28.

A m o m e n t ’s reflection only is necessary to convince the lover o f nature that the creatures inhabiting the

great waters are as numerous and as varied in their forms as those dwelling on the land, and that, were the

mighty deep to unfold to us the whole o f its treasures, we should find that they comprise objects of beauty

and colouriug as numerous, if not more so, as those o f the air. Among aquatic birds, two very extensive

families are found to exist preeminently fitted to frequent the face o f the ocean, namely the Petrels and the

Auks. The greater number o f the former inhabit the seas south o f the equator, as the latter do almost

exclusively those north of it. The members o f the Procellariidce, or Petrels, feed principally on the lower

Physalice, and the Alcidae or Auks on the smaller fishes ; by which means the balance o f animal life is maintained,

and probably ever will be so, as long as Nature’s laws are not interfered with by man. To ruthlessly kill

the oceanic birds when they seek our rock-bound islands for the purpose o f reproduction is surely a mistake;

for the result would be an excess o f such fishes as the herring, the mackerel, and the pilchard, upon the fry

o f which most o f our sea-birds feed; and such an excess would probably be accompanied by diseases such as

sometimes occur among our birds and quadrupeds when redundant in number.

These observations may appear trivial; but I have penned them as they occurred to me when sitting down

to write the history o f the Common Guillemot, numerically perhaps the most abundant member of its family,

if not o f the whole o f our sea-birds.

In a broad sense, I may say that this well-known bird is strictly confined to the northern hemisphere

where its range extends from the borders o f the Arctic circle to the latitude o f Madeira and the Azores.

Always at sea during the months o f autumn and winter, it dwells day and night on the face o f the water,

seldom flying unless from one part o f its fishing-bank to another. On the commencement-of spring the

promptings o f nature induce it to approach the land and resort to those coasts whose rocky precipices afford

a resting-place for its large singularly formed egg. Some time after incubation has been effected, the parent

takes its young down to the sea, sheltered bays and more quiet firths being then resorted to, such situations

appearing to afford a certain degree o f protection to the young until they have acquired sufficient power to

enable them to proceed to the open waters destined for their future abiding-place. In the comparatively

little-disturbed waters alluded to, the fry o f the herring, the pilchard, the sprat, and other fishes are found,

the whole affording an abundant supply of nutriment to the birds both old and young.

To enumerate individually the breeding-places of the Guillemot in the British Islands is quite unnecessary,

since they are to be found from the Land’s End, in Cornwall, to the coasts o f Wales, to Yorkshire, to Ailsa

Craig, the northern and other parts o f Scotland, and the Hebrides. Similar situations o f a favourable character

in the sister kingdom o f Ireland are all more or less resorted to by this bird, which, moreover, is equally

numerous in all suitable localities in the northern portions o f the continent of Europe and America.

I have alluded to the immense numbers o f this bird in all the localities frequented by i t ; and in illustration

of this assertion, I cannot perhaps do better than give the following paragraph from an interesting paper by

Mr. Robert Gray on Ailsa Craig and its inhabitants, published in the ‘ Intellectual Observer,’ vol. iv.

p. 119 &c.

“ The Guillemot and Razorbill breed on the narrow ledges of rock occupying the entire face of the highest

precipices of Ailsa Crag, and presenting, when viewed from the sea, a very remarkable and orderly appearance.

They make no nest, but lay their single egg upon the bare ledge, which is seldom more than six inches in

breadth ; so that each bird is compelled to sit erect when incubating. I have frequently climbed to a height