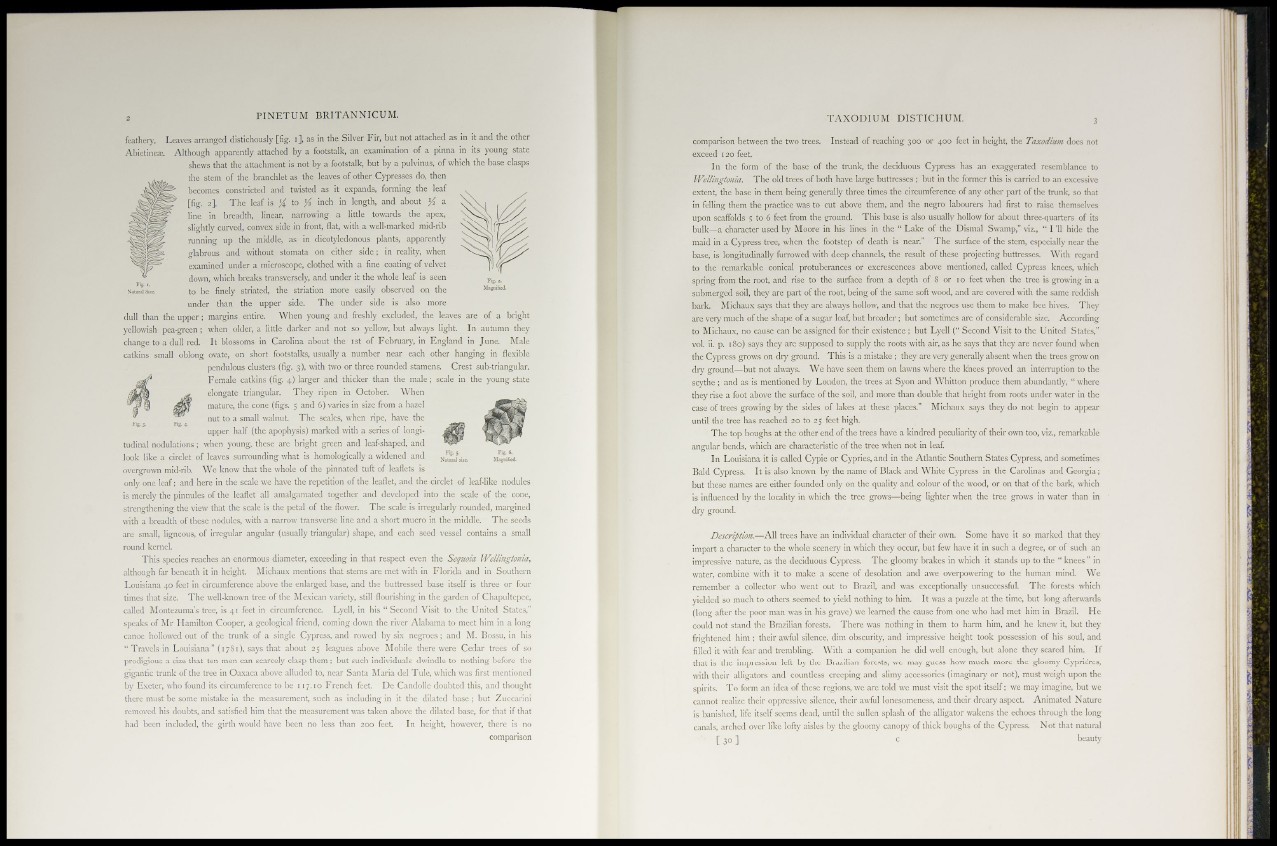

feathery. Leaves arranged distichously [fig. i], as in the Silver Fir, but not attached as in it and the other

Abietineae. Although apparently attached by a footstalk, an examination of a pinna in its young state

shews that the attachment is not by a footstalk, but by a pulvinus, of which the base clasps

the stem of the branchlet as the leaves of other Cypresses do, then

becomes constricted and twisted as it expands, forming the leaf

[fig. 2]. The leaf is % to ]/z inch in length, and about Yz a

line in breadth, linear, narrowing a little towards the apex,

slightly curved, convex side in front, flat, with a well-marked mid-rib

running up the middle, as in dicotyledonous plants, apparently

o-labrous and without stomata on either side; in reality, when

examined under a microscope, clothed with a fine coating of velvet

clown, which breaks transversely, and under it the whole leaf is seen

of a bright

Natural size. to be finely striated, the striation more easily observed on the

under than the upper side. The under side is also more

dull than the upper; margins entire. When young and freshly excluded, the leaves ;

yellowish pea-green ; when older, a little darker and not so yellow, but always light. In autumn they

change to a dull red. It blossoms in Carolina about the 1st of February, in England in June. Male

catkins small oblong ovate, on short footstalks, usually a number near each other hanging in flexible

pendulous clusters (fig. 3), with two or three rounded stamens. Crest sub-triangular.

Female catkins (fig. 4) larger and thicker than the male; scale in the young state

elongate triangular. They ripen in October. When

mature, the cone (figs. 5 and 6) varies in size from a hazel

nut to a small walnut. The scales, when ripe, have the

upper half (the apophysis) marked with a series of longiwhen

young, these are bright green and leaf-shaped, and

look like a circlet of leaves surrounding what is homologically a widened and N^5'si21, Magoifi«i.

overgrown mid-rib. We know that the whole of the pinnated tuft of leaflets is

only one leaf; and here in the scale we have the repetition of the leaflet, and the circlet of leaf-like nodules

is merely the pinnules of the leaflet all amalgamated together and developed into the scale of the cone,

strengthening the view that the scale is the petal of the flower. The scale is irregularly rounded, margined

with a breadth of these nodules, with a narrow transverse line and a short mucro in the middle. The seeds

are small, ligneous, of irregular angular (usually triangular) shape, and each seed vessel contains a small

round kernel.

This species reaches an enormous diameter, exceeding in that respect even the Sequoia Wellingtonia,

although far beneath it in height. Michaux mentions that stems are met with in Florida and in Southern

Louisiana 40 feet in circumference above the enlarged base, and the buttressed base itself is three or four

times that size. The well-known tree of the Mexican variety, still flourishing in the garden of Chapultcpec,

called Montezuma's tree, is 41 feet in circumference. Lyell, in his " Second Visit to the United States,"

speaks of Mr Hamilton Cooper, a geological friend, coming down the river Alabama to meet him in a long

canoe hollowed out of the trunk of a single Cypress, and rowed by six negroes; and M. Bossu, in his

" Travels in Louisiana " (1781), says that about 25 leagues above Mobile there were Cedar trees of so

prodigious a size that ten men can scarcely clasp them ; but such individuals dwindle to nothing before the

gigantic trunk of the tree in Oaxaca above alluded to, near Santa Maria del Tule, which was first mentioned

by Exeter, who found its circumference to be 117.10 French feet. Dc Candolle doubted this, and thought

there must be some mistake in the measurement, such as including in it the dilated base ; but Zuccarini

removed his doubts, and satisfied him that the measurement was taken above the dilated base, for that if that

had been included, the girth would have been no less than 200 feet. In height, however, there is no

comparison

tudinal nodulations;

comparison between the two trees. Instead of reaching 300 or 400 feet in height, the Taxodmm does not

exceed 120 feet.

In the form of the base of the trunk, the deciduous Cypress has an exaggerated resemblance to

Wellingtonia. The old trees of both have large buttresses ; but in the former this is carried to an excessive

extent, the base in them being generally three times the circumference of any other part of the trunk, so that

in felling them the practice was to cut above them, and the negro labourers had first to raise themselves

upon scaffolds 5 to 6 feet from the ground. This base is also usually hollow for about three-quarters of its

bulk—a character used by Moore in his lines in the " Lake of the Dismal Swamp," viz., " I '11 hide the

maid in a Cypress tree, when the footstep of death is near." The surface of the stem, especially near the

base, is longitudinally furrowed with deep channels, the result of these projecting buttresses. With regard

to the remarkable conical protuberances or excrescences above mentioned, called Cypress knees, which

spring from the root, and rise to the surface from a depth of 8 or 1 o feet when the tree is growing in a

submerged soil, they are part of the root, being of the same soft wood, and are covered with the same reddish

bark. Michaux says that they are always hollow, and that the negroes use them to make bee hives. They

are very much of the shape of a sugar loaf, but broader; but sometimes are of considerable size. According

to Michaux, no cause can be assigned for their existence ; but Lyell (" Second Visit to the United States,"

vol. ii. p. 180) says they are supposed to supply the roots with air, as he says that they are never found when

the Cypress grows on dry ground. This is a mistake ; they are very generally absent when the trees grow on

diy ground—but not always. We have seen them on lawns where the knees proved an interruption to the

scythe ; and as is mentioned by Loudon, the trees at Syon and Whitton produce them abundantly, " where

they rise a foot above the surface of the soil, and more than double that height from roots under water in the

case of trees growing by the sides of lakes at these places." Michaux says they do not begin to appear

until the tree has reached 20 to 25 feet high.

The top boughs at the other end of the trees have a kindred peculiarity of their own too, viz., remarkable

angular bends, which are characteristic of the tree when not in leaf.

In Louisiana it is called Cypie or Cypries, and in the Atlantic Southern States Cypress, and sometimes

Bald Cypress. It is also known by the name of Black and White Cypress in the Carolinas and Georgia;

but these names are either founded only on the quality and colour of the wood, or on that of the bark, which

is influenced by the locality in which the tree grows—being lighter when the tree grows in water than in

dry ground.

Description.—All trees have an individual character of their own. Some have it so marked that they

impart a character to the whole scenery in which they occur, but few have it in such a degree, or of such an

impressive nature, as the deciduous Cypress. The gloomy brakes in which it stands up to the " knees " in

water, combine with it to make a scene of desolation and awe overpowering to the human mind. We

remember a collector who went out to Brazil, and was exceptionally unsuccessful. The forests which

yielded so much to others seemed to yield nothing to him. It was a puzzle at the time, but long afterwards

(long after the poor man was in his grave) we learned the cause from one who had met him in Brazil. He

could not stand the Brazilian forests. There was nothing in them to harm him, and he knew it, but they

frightened him ; their awful silence, dim obscurity, and impressive height took possession of his soul, and

filled it with fear and trembling. With a companion he did well enough, but alone they scared him. If

that is the impression left by the Brazilian forests, we may guess how much more the gloomy Cyprieres,

with their alligators and countless creeping and slimy accessories (imaginary or not), must weigh upon the

spirits. To form an idea of these regions, we are told we must visit the spot itself; we may imagine, but we

cannot realize their oppressive silence, their awful lonesomeness, and their dreary aspect. Animated Nature

is banished, life itself seems dead, until the sullen splash of the alligator wakens the echoes through the long

canals, arched over like lofty aisles by the gloomy canopy of thick boughs of the Cypress. Not that natural

[ 30 ] c beauty