it shrinks in bulk one-seventieth part in drying. But the weight of all wood varies according to the

age of the tree from which it is taken, and also according to the rapidity of its growth and the

nature of the locality in which it has been grown. Consequently, no absolute dependence can be placed

upon the results obtained from such experiments. But perhaps the data which deserve most attention

are those given in Brown's " Forester," pp. 630, 635, in tables composed by Mr Rait, the forester at

Castle Forbes, Aberdeenshire, embodying the results of many years' labour and study in experiments on

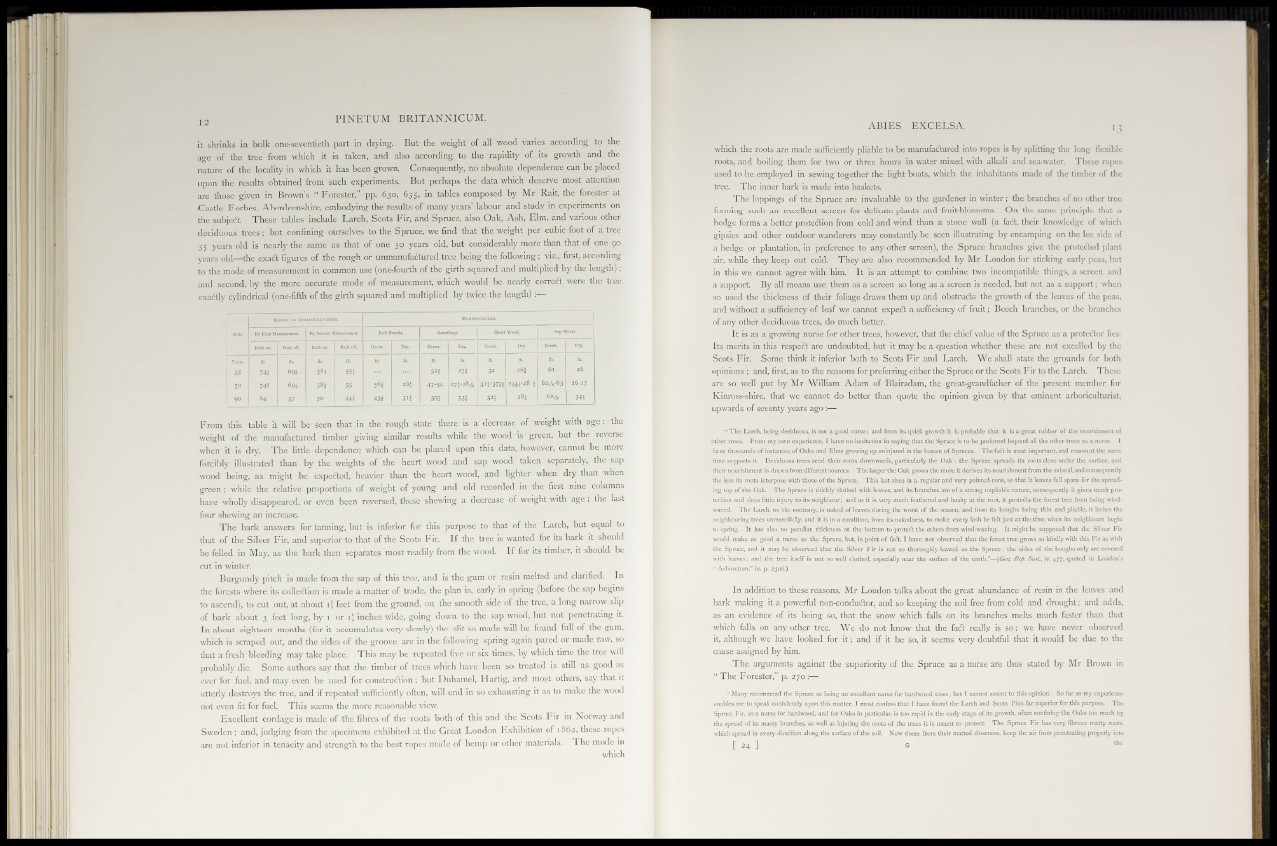

the subject. These tables include Larch, Scots Fir, and Spruce, also Oak, Ash, Elm, and various other

deciduous trees; but confining ourselves to the Spruce, we find that the weight per cubic foot of a tree

35 years old is nearly the same as that of one 50 years old, but considerably more than that of one 90

years old—the exact figures of the rough or unmanufactured tree being the following; viz., first, according

to the mode of measurement in common use (one-fourth of the girth squared and multiplied by the length) ;

and second, by the more accurate mode of measurement, which would be nearly correct were the tree

exactly cylindrical (one-fifth of the girth squared and multiplied by twice the length) :—

695-

69» s 24^-28 ? | 62^,-63

Si I 62*

From this table it will be seen that in the rough state there is a decrease of weight with age: the

weight of the manufactured timber giving similar results while the wood is green, but the reverse

when it is dry. The little dependence which can be placed upon this data, however, cannot be more

forcibly illustrated than by the weights of the heart wood and sap wood taken separately, the sap

wood being, as might be expected, heavier than the heart wood, and lighter when dry than when

green; while the relative proportions of weight of young and old recorded in the first nine columns

have wholly disappeared, or even been reversed, these shewing a decrease of weight with age; the last

four shewing an increase.

The bark answers for tanning, but is inferior for this purpose to that of the Larch, but equal to

that of the Silver Fir, and superior to that of the Scots Fir. If the tree is wanted for its bark it should

be felled in May, as the bark then separates most readily from the wood. If for its timber, it should be

cut in winter.

Burgundy pitch is made from the sap of this tree, and is the gum or resin melted and clarified. In

the forests where its collection is made a matter of trade, the plan is, early in spring (before the sap begins

to ascend), to cut out, at about i; feet from the ground, on the smooth side of the tree, a long narrow slip

of bark about 3 feet long, by 1 or 15 inches wide, going down to the sap wood, but not penetrating it.

In about eighteen months (for it accumulates very slowly) the slit so made will be found full of the gum,

which is scraped out, and the sides of the groove are in the following spring again pared or made raw, so

that a fresh bleeding may take place. This may be repeated five or six times, by which time the tree will

probably die. Some authors say that the timber of trees which have been so treated is still as good as

ever for fuel, and may even be used for construction; but Duhamel, Hartig, and most others, say that it

utterly destroys the tree, and if repeated sufficiently often, will end in so exhausting it as to make the wood

not even fit for fuel. This seems the more reasonable view.

Excellent cordage is made of the fibres of the roots both of this and the Scots Fir in Norway and

Sweden; and, judging from the specimens exhibited at the Great London Exhibition of 1862, these ropes

are not inferior in tenacity and strength to the best ropes made of hemp or other materials. The mode in

which

which the roots are made sufficiently pliable to be manufactured into ropes is by splitting the long flexible

roots, and boiling them for two or three hours in water mixed with alkali and sea-water. These ropes

used to be employed in sewing together the light boats, which the inhabitants made of the timber of the

tree. The inner bark is made into baskets.

The loppings of the Spruce are invaluable to the gardener in winter; the branches of no other tree

forming such an excellent screen for delicate plants and fruit-blossoms. On the same principle that a

hedge forms a better protection from cold and wind than a stone wall (a fact, their knowledge of which

gipsies and other outdoor wanderers may constantly be seen illustrating by encamping on the lee side of

a hedge or plantation, in preference to any other screen), the Spruce branches give the protected plant

air, while they keep out cold. They are also recommended by Mr Loudon for sticking early peas, but

in this we cannot agree with him. It is an attempt to combine two incompatible things, a screen and

a support. By all means use them as a screen so long as a screen is needed, but not as a support; when

so used the thickness of their foliage draws them up and obstructs the growth of the leaves of the peas,

and without a sufficiency of leaf we cannot expect a sufficiency of fruit; Beech branches, or the branches

of any other deciduous trees, do much better.

It is as a growing nurse for other trees, however, that the chief value of the Spruce as a protector lies.

Its merits in this respect are undoubted, but it may be a question whether these are not excelled by the

Scots Fir. Some think it inferior both to Scots Fir and Larch. We shall state the grounds for both

opinions ; and, first, as to the reasons for preferring either the Spruce or the Scots Fir to the Larch. These

are so well put by Mr William Adam of Blairadam, the great-grandfather of the present member for

Kinross-shire, that we cannot do better than quote the opinion given by that eminent arboriculturist,

upwards of seventy years ago :—

•' The Larch, being deciduous, is not a good nurse! and from its quick growth it is probable that it is a great robber of the nourishment of

other trees. From my own experience, I have no hesitation in saying that the Spruce is to be preferred beyond all the other trees as a nurse. I

have thousands of instances of Oaks and Elms growing up uninjured in the bosom of Spruces. The fail is most important, and reason at the same

time supports it. Deciduous trees send their roots downwards, particularly the Oak : the Spruce spreads its roots close under the surface, and

their nourishment is drawn from different sources. The larger the Oak grows the more it derives its nourishment from the subsoil, and consequently

the less its roots interpose with those of the Spruce. This last rises in a regular and very pointed cone, so that it leaves full space for the spreading

top of the Oak. The Spruce is thickly clothed with leaves, and its branches are of a strong unpliable nature, consequently it gives much protedlion

and does little injury to its neighbour; and as it is very much feathered and bushy at the root, it proteifls the forest tree from being windwaved.

The Larch, on the contrary, is naked of leaves during the worst of the season, and from its boughs being thin and pliable, it lashes the

neighbouring trees unmercifully, and it is in a condition, from its nakedness, to make every lash be felt just at the time when its neighbours begin

to spring. It has also no peculiar thickness at the bottom to proteft the others from wind-waving. It might be supposed that the Silver Fir

would make as good a nurse as the Spruce, but, in point of fa£l, I have not observed that the forest tree grows so kindly with this Fir as with

the Spruce, and it may be observed that the Silver Fir is not so thoroughly leaved as the Spruce: the sides of the boughs only are covered

with leaves; and the tree itself is not so well clothed, especially near the surface of the earth."—(Gen. Rep. Scot., iv. 477, quoted in Loudon's

" Arboretum," iv. p. 2306.)

In addition to these reasons, Mr Loudon talks about the great abundance of resin in the leaves and

bark making it a powerful non-conductor, and so keeping the soil free from cold and drought; and adds,

as an evidence of its being so, that the snow which falls on its branches melts much faster than that

which falls on any other tree. We do not know that the fact really is so; we have never observed

it, although we have looked for it; and if it be so, it seems very doubtful that it would be due to the

cause assigned by him.

The arguments against the superiority of the Spruce as a nurse are thus stated by Mr Brown in

" The Forester," p. 270:—

" Many recommend the Spruce as being an excellent nurse for hardwood trees; but I cannot assent to this opinion. So far as my experience

enables me to speak confidently upon this matter, I must confess that I have found the Larch and Scots Pine far superior for this purpose. The

Spruce Fir, as a nurse for hardwood, and for Oaks in particular, is too rapid in the early stage of its growth, often confining the Oaks too much by

the spread of its massy branches, as well as injuring the roots of the trees it is meant to protect The Spruce Fir has very fibrous matty roots,

which spread in every direction along the surface of the soil. Now these, from their matted closeness, keep the air from penetrating properly into