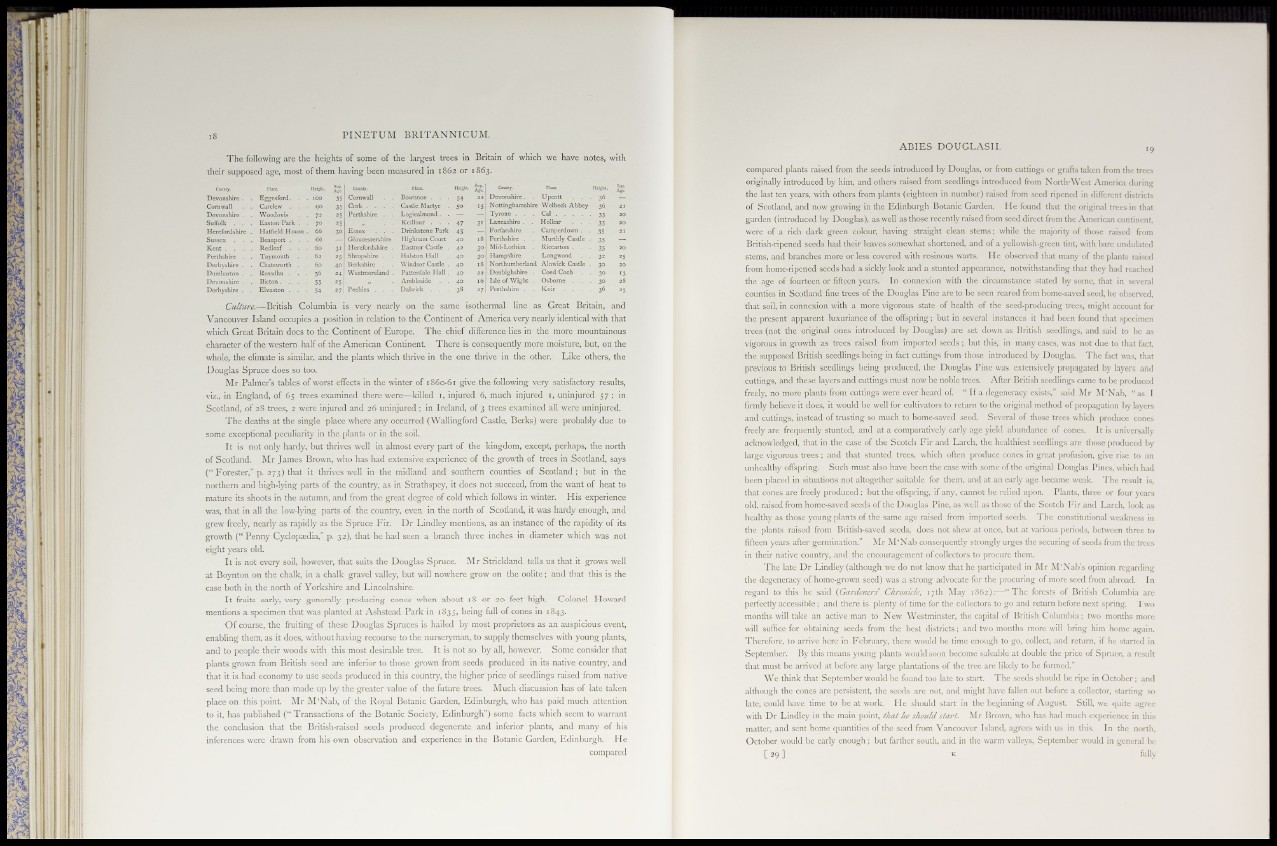

The following are the heights of some of the largest trees in Britain of which we have notes, with

their supposed age, most of them having been measured in 1862 or 1863.

County, Hci£hi. & County. PL-.cc Height. Age." COrnty. PI.™. Mgbl. g'

Devonshire . Eggesford. . 100 35 Cornwall . . Bownnoe . . . 54 22 Devonshire. . Upcott . . . 36 —

Cornwall Carclew . . go 35 Castle Martyr . 50 15 Nottinghamshire Welbeck Abbey 36 2.

Devonshire . Woodovis • 72 25 Perthshire . . Logiealmond. . — — Tyrone . . . Cal 35 20

Suffolk . . Easton Park . • 7° 25 Keillour . . . 47 31 Lancashire . . Holkar . . . 35 20

Herefordshire Hatfield House . 66 30 Essex . . . Drinkstone Park 45 — Forfarshire Camperdown . . 35 21

Sussex . . Beauport . . . 66 — Gloucestershire Highnam Coin 40 l8 Perthshire . . Murthly Castle . 35 —

Kent . . . Redleaf . . . 60 3" Herefordshire . Eastnor Castle , 42 3° Mid-Lothian Riccarton . . . 35 20

Perthshire . Taymouth . 62 25 Shropshire , . Halston Hall . 40 30 Hampshire Longwood . . 32 25

Derbyshire . Chatsworth . . 60 40 Berkshire . . Windsor Castle . 40 l8 Northumberland Alnwick Castle . 30 20

Dumbarton . Rossdhu . . • 56 24 Westmoreland . Patterdale Hall . 40 22 Denbighshire . Coed Coch . . 3 0 13

Devonshire . Bicton. . . • 55 25 Ambleside . . 40 16 Isle of Wight . Osborne . . . 3 0 28

Derbyshire . Elvaston . . • 54 27 Peebles . . . Dalwick . . . 38 27 Perthshire . . Keir . . . . 36 25

Culture.—British Columbia is very nearly on the same isothermal line as Great Britain, and

Vancouver Island occupies a position in relation to the Continent of America very nearly identical with that

which Great Britain does to the Continent of Europe. The chief difference lies in the more mountainous

character of the western half of the American Continent. There is consequently more moisture, but, on the

whole, the climate is similar, and the plants which thrive in the one thrive in the other. Like others, the

Douglas Spruce does so too.

Mr Palmer's tables of worst effects in the winter of 1860-61 give the following very satisfactory results,

viz., in England, of 65 trees examined there were—killed 1, injured 6, much injured 1, uninjured 57 ; in

Scotland, of 28 trees, 2 were injured and 26 uninjured ; in Ireland, of 3 trees examined all were uninjured.

The deaths at the single place where any occurred (Wallingford Castle, Berks) were probably due to

some exceptional peculiarity in the plants or in the soil.

It is not only hardy, but thrives well in almost every part of the kingdom, except, perhaps, the north

of Scotland. Mr James Brown, who has had extensive experience of the growth of trees in Scotland, says

(" Forester," p. 273) that it thrives well in the midland and southern counties of Scotland; but in the

northern and high-lying parts of the country, as in Strathspey, it does not succeed, from the want of heat to

mature its shoots in the autumn, and from the great degree of cold which follows in winter. His experience

was, that in all the low-lying parts of the country, even in the north of Scotland, it was hardy enough, and

grew freely, nearly as rapidly as the Spruce Fir. Dr Lindley mentions, as an instance of the rapidity of its

growth (" Penny Cyclopaedia," p. 32), that he had seen a branch three inches in diameter which was not

eight years old.

It is not every soil, however, that suits the Douglas Spruce. Mr Strickland tells us that it grows well

at Boynton on the chalk, in a chalk gravel valley, but will nowhere grow on the oolite; and that this is the

case both in the north of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

It fruits early, very generally producing cones when about 18 or 20 feet high. Colonel Howard

mentions a specimen that was planted at Ashstead Park in 1835, being full of cones in 1843.

Of course, the fruiting of these Douglas Spruces is hailed by most proprietors as an auspicious event,

enabling them, as it does, without having recourse to the nurseryman, to supply themselves with young plants,

and to people their woods with this most desirable tree. It is not so by all, however. Some consider that

plants grown from British seed are inferior to those grown from seeds produced in its native country, and

that it is bad economy to use seeds produced in this country, the higher price of seedlings raised from native

seed being more than made up by the greater value of the future trees. Much discussion has of late taken

place on this point. Mr M'Nab, of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, who has paid much attention

to it, has published (" Transactions of the Botanic Society, Edinburgh") some facts which seem to warrant

the conclusion that the British-raised seeds produced degenerate and inferior plants, and many of his

inferences were drawn from his own observation and experience in the Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. He

compared

compared plants raised from the seeds introduced by Douglas, or from cuttings or grafts taken from the trees

originally introduced by him, and others raised from seedlings introduced from North-West America during

the last ten years, with others from plants (eighteen in number) raised from seed ripened in different districts

of Scotland, and now growing in the Edinburgh Botanic Garden. He found that the original trees in that

garden (introduced by Douglas), as well as those recently raised from seed direct from the American continent,

were of a rich dark green colour, having straight clean stems; while the majority of those raised from

British-ripened seeds had their leaves somewhat shortened, and of a yellowish-green tint, with bare undulated

stems, and branches more or less covered with resinous warts. He observed that many of the plants raised

from home-ripened seeds had a sickly look and a stunted appcarance, notwithstanding that they had reached

the age of fourteen or fifteen years. In connexion with the circumstance stated by some, that in several

counties in Scotland fine trees of the Douglas Pine are to be seen reared from home-saved seed, he observed,

that soil, in connexion with a more vigorous state of health of the seed-producing trees, might account for

the present apparent luxuriance of the offspring; but in several instances it had been found that specimen

trees (not the original ones introduced by Douglas) are set down as British seedlings, and said to be as

vigorous in growth as trees raised from imported seeds ; but this, in many cases, was not due to that fact,

the supposed British seedlings being in fact cuttings from those introduced by Douglas. The fact was, that

previous to British seedlings being produced, the Douglas Pine was extensively propagated by layers and

cuttings, and these layers and cuttings must now be noble trees. After British seedlings came to be produced

freely, no more plants from cuttings were ever heard of. " If a degeneracy exists," said Mr M'Nab, "as I

firmly believe it does, it would be well for cultivators to return to the original method of propagation by layers

and cuttings, instead of trusting so much to home-saved seed. Several of those trees which produce cones

freely are frequently stunted, and at a comparatively early age yield abundance of concs. It is universally

acknowledged, that in the case of the Scotch Fir and Larch, the healthiest seedlings are those produced by

large vigorous trees ; and that stunted trees, which often produce cones in great profusion, give rise to an

unhealthy offspring. Such must also have been the case with some of the original Douglas Pines, which had

been placed in situations not altogether suitable for them, and at an early age became weak. The result is,

that cones are freely produced ; but the offspring, if any, cannot be relied upon. Plants, three or four years

old, raised from home-saved seeds of the Douglas Pine, as well as those of the Scotch Fir and Larch, look as

healthy as those young plants of the same age raised from imported seeds. The constitutional weakness in

the plants raised from British-saved seeds, does not shew at once, but at various periods, between three to

fifteen years after germination." Mr M'Nab consequently strongly urges the securing of seeds from the trees

in their native country, and the encouragement of collectors to procure them.

The late Dr Lindley (although we do not know that he participated in Mr M'Nab's opinion regarding

the degeneracy of home-grown seed) was a strong advocate for the procuring of more seed from abroad. In

regard to this he said (Gardeners' Chronicle, 17th May 1862);—"The forests of British Columbia are

perfectly accessible; and there is plenty of time for the collectors to go and return before next spring. Two

months will take an active man to New Westminster, the capital of British Columbia; two months more

will suffice for obtaining seeds from the best districts; and two months more will bring him home again.

Therefore, to arrive here in February, there would be time enough to go, collect, and return, if he started in

September. By this means young plants would soon become saleable at double the price of Spruce, a result

that must be arrived at before any large plantations of the tree are likely to be formed."

We think that September would be found too late to start. The seeds should be ripe in October; and

although the cones are persistent, the seeds are not, and might have fallen out before a collector, starting so

late, could have time to be at work. He should start in the beginning of August. Still, we quite agree

with Dr Lindley in the main point, that he should start. Mr Brown, who has had much experience in this

matter, and sent home quantities of the seed from Vancouver Island, agrees with us in this. In the north,

October would be early enough ; but farther south, and in the warm valleys, September would in general be

[ 29 ] K fully