longer in California, and explored it more thoroughly than he would otherwise have done ; but, in the end of

the summer of 1832, despairing of a more direct opportunity, he sailed for the Sandwich Islands, which he

reached in August 1832, and from thence found a vessel for the Columbia, where he arrived on 24th October

1832. He continued there until October, during which time he extended his explorations on every side.

He visited the Blue Mountains, and attempted the ascent of Mount Hood. He also commenced "an

exploration" to the north, by Fraser's River; but it was brought to a premature termination by the

upsetting of his canoe, at the Stony Islands of Fraser's River. By this catastrophe, his Journal and botanical

notes, besides his collection of plants, and all the articles needful for pursuing his journey, were destroyed.

He himself escaped with difficulty. He was carried over the cataract, and gained the shore in a whirlpool

below ; not, however, by swimming, for he was rendered helpless, and the waves dashed him on the rocks.

Having now taken the cream of botanical discovery in North-West America, he thought of returning to

England by Siberia, and perhaps attempting to penetrate to Pekin on the way. Baron Wrangel, Governor

of the Russian Territories in America, wrote him, offering him every assistance and encouragement, and his

friends in England had prepared his way by interesting the Russian Government in his behalf. Dr Hooker

thinks that, in his later letters, he seemed to have given up this purpose, and to have turned his thoughts

towards England. But, subsequently to the letters from which Dr Hooker judged, it would appear that he

still cherished the idea, for Mr Beale (Beale's "Sperm Whale," p. 362) mentions that Douglas informed him,

when he saw him at Oahoo shortly before his tragic death, that in a short time he intended to commence his

journey homewards, through Siberia and Russia, wishing, as he stated, to inspect some platina mines which

had just then been discovered in Siberia.

In October 1833, he bade adieu to NorthWest America, and sailed for the Sandwich Islands, which

he reached on 23d December, touching, but not botanising, at San Francisco. He landed at Oahoo, but

shortly after proceeded to Hawaii, his object being to'ascend and explore the lofty volcanic mountains, Mouna

Kuah and Mouna Roa. Both of these he ascended, and a graphic and interesting account of his ascents,

given in the last of his Journals, will be found in the " Companion to the Botanical Magazine," vol. ii.,

p. 161, from which the vignette portrait of Douglas, at the end of this article, is copied. Two months later,

his wanderings were over. In one of them he fell into a pit excavated for the purpose of taking wild cattle,

and was killed by a bullock which had previously fallen into it. Such was the melancholy end of one of

the ablest, certainly the most successful, of botanical collectors. There have been collectors who contributed

more to botanical knowledge—and collectors, perhaps, who have made more extensive collections—but none

who have contributed more to the stock of hardy plants introduced into England. He had the rare good

fortune to be sent to a country which was at the same time fertile in novelties, and, what was of still more

importance, one possessing a climate similar to our own.

Properties and Uses.—Whether it maybe ultimately ascertained that there are two species of Abies

Douglasii, or only one, it is obviously desirable that, in the meantime, all that is known of the properties and

uses of the two supposed species should be kept distinct and apart. We shall say what we know of

each under their separate heads.

Of the Oregon variety, Dr Lindley says (" Penny Cyclop.," i., p. 32) that the timber is heavy, firm, and

of as deep a colour as the yew, with very few knots, and not in the least liable to warp. " We have," said he,

" a plank now before us, which, after standing some years in a hot room, is as straight, and its grain as

compact, as the first day it was placed ;" and more recently (Gardeners' Chronicle, 17th May 1862) he gave

it as an ascertained fact that it is unsurpassable in the qualities which render timber most valuable ; that it

is clean grained, strong, elastic, light, and acquires large dimensions in ungenial climates; that it thrives

everywhere in the United Kingdom, except the extreme north, and is, therefore, of all trees that which most

deserves the attention of planters for profit. To which we may add, that no evergreen surpasses it as an

ornament of scenery.

Dr Cooper, in that section of the " United States Pacific Railroad Reports'' which relates to British

Columbia,

Columbia, says, that the wood is rather coarse grained and liable to shrink; but is more used for lumber

than any other, being adapted for all kinds of rough work exposed to the weather.

Dr Newberry, whose report relates chiefly to the district of the Willamette Valley, a little farther to

the south, says that the timber, like that of most of the Spruces, is harder and less pleasant to work than

that of the Pines. It is, however, veiy stiff, makes excellent planking, joists, and timber, and for these

purposes it is veiy largely used both in Oregon and California.

The wood, according to Dr Bigelow, again (op. cit., iv. 17), is coarse grained, rough, and hard, so

much so as to preclude its being used as Pine lumber; but it forms most excellent building timber. At

San Francisco, Sacramento, and other cities of California, its timber is used almost exclusively for making

plank roads, side walks, and piling; and, as we have already said, on the same authority, probably onefourth

of the city of San Francisco is thus built on piles, and the wharves at the latter place are built

exclusively of this timber. Now that a railway crosses the Rocky Mountains, it will furnish railway tires,

equal, if not superior, to those of any other wood in the west.

There may be some little doubt as to which of the varieties Dr Bigelow speaks of, as he passed the

districts of both ; but from his references to San Francisco and other cities, it is plain that, so far as

regards them, he is speaking of the Coast variety.

Mr Robert Brown (the Collector for the British Columbia Botanical Association), whose experience

of it, though extending over the whole extent of the Pacific slope of the Rocky Mountains, was yet more

especially extensive in British Columbia, where the tree attains its maximum of development, speaks of it

as liable to warp—in this respect differing from the statement by Dr Lindley, above referred to. In a

private note, with which we were favoured by Mr Brown, he states that houses built of boards sawn from fresh

timber will so contract as to leave a space of between one and two inches between the edges of the boards.

Its strength and tenacity, however, are well vouched for. The following notes upon these points are quoted

from a French Official Report made by M. Serress, Naval Engineer, Cherbourg, dated 6th April i860:—

" Twelve specimens of squared mast timber (Adits Douglasii) from Vancouver Island were sent to Cherbourg by Mr Thatcher in order to be

experimented upon. They were all placed amongst limber of the first class; they were almost wholly free from knots throughout the main trunk,

and the few knots, which were at the head, were small, and adhered closely to the surrounding wood.

When received, the wood appeared very flexible; the pieces token off the angles, in the proccss of rounding the masts, were very long, and

capable of being twisted several times without breaking.

" Resistance. In order to determine the resistance of the new wood it was compared with Florida Pine,' Pin du Nord (Scotch Pine?), and

Canada Pine, specimens of each being bent until they broke.

" The pieces experimented upon were 0.493 metre in length and 0.045 square metre in sectional area. These pieces were placed on two

knife edges, 0.40 metre apart, and were bent by means of pressure applied to a third edge between the other two. Each time the pressure was

applied, it was continued until the flexure had remained constant for about a minute, when the pressure was removed, in order that the elasticity

of the wood might be ascertained. Beginning with a weight of 200 kilos., the pressure was increased by 50 kilos., at a time, until the wood broke.

I he following table shews the average pressure at which the picces experimented upon broke :—Florida, 870 kilos.; Vancouver, 866 kilos. ; Nord,

800 kilos.; Canada, 635 kilos."

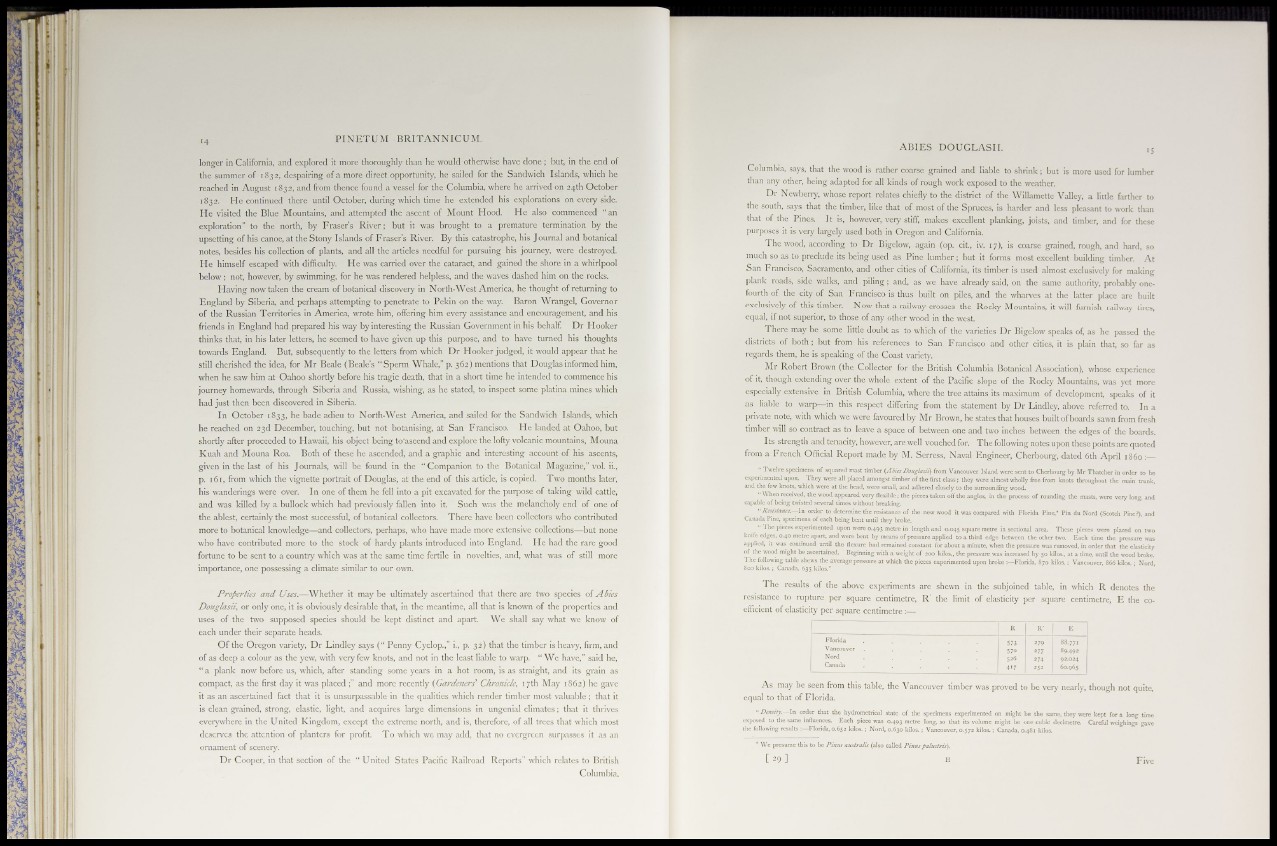

The results of the above experiments are shewn in the subjoined table, in which R denotes the

resistance to rupture per square centimetre, R' the limit of elasticity per square centimetre, E the coefficient

of elasticity per square centimetre:—

89.492

92.024

60.965

As may be seen from this table, the Vancouver timber was proved to be very nearly, though not quite,

equal to that of Florida.

"Density. In order that the hydrometrical state of the specimens experimented on might be the same, they were kept for a long time

exposed to the same influences. Kach piece was 0.493 metre long, so that its volume might be one cubic decimetre. Careful weighings gave

the following results :—Florida, 0.652 kilos.; Nord, 0.630 kilos.; Vancouver, 0.572 kilos.; Canada, 0.481 kilos.

' We presume this to be Pinus australis (also called Pinus fialuslris).

[ 2 9 ] h Five