broil, amidst his efforts, has the blood settled in his face. The

following picture is truly horrible from its truth and accuracy:

But, see, his face is black, and full of blood;

His eyeballs further out than when he lived,

Staring full ghastly like a strangled man:

His hair uprear’d, his nostrils stretch’d with struggling;

His hands abroad display’d as one that grasp’d

And tugg’d for life, and was by strength subdued.

Look on the sheets; his hair, you see, is sticking;

His well proportion’d beard made rough and rugged,

Like to the summer’s corn by tempest lodged.

It cannot be, but he was murder’d here;

The least of all these signs were probable.

K in g H e n r y VI. Part II.

The laws of inquest in this country require us to witness such

things in all their horrible circumstance, since the body lies where

it falls, and no weapon or even disorder of dress is removed. “ The

blood is black and stiff, in strong contrast with the paleness of the

face. Yet there is some colour in the face, it is pale yellow, stained

with light blue and purple on the temple, eyelids, and sides of the

nose. The eyes are closed, but why so different from sleep ? a

nearer inspection shows that in the agony the under eyelids are

drawn under the upper ones. The jaws are clenched, and the

tongue caught betwixt the teeth.” This young man had put a

pistol to his head.

Are such scenes to be represented ? Certainly not. But they

are to be conceived by those, who consistently with good taste, are,

in a manner less obtrusive and circumstantial, to convey an impression

to the spectator, to that mind which may be awakened to

sensation without all the disgusting circumstances of the actual

scene. We may have it in words, as Shakspeare has represented

the body of the good Duke Humphry. But in painting, the material

makes the representation too true to admit the whole features

of horror.

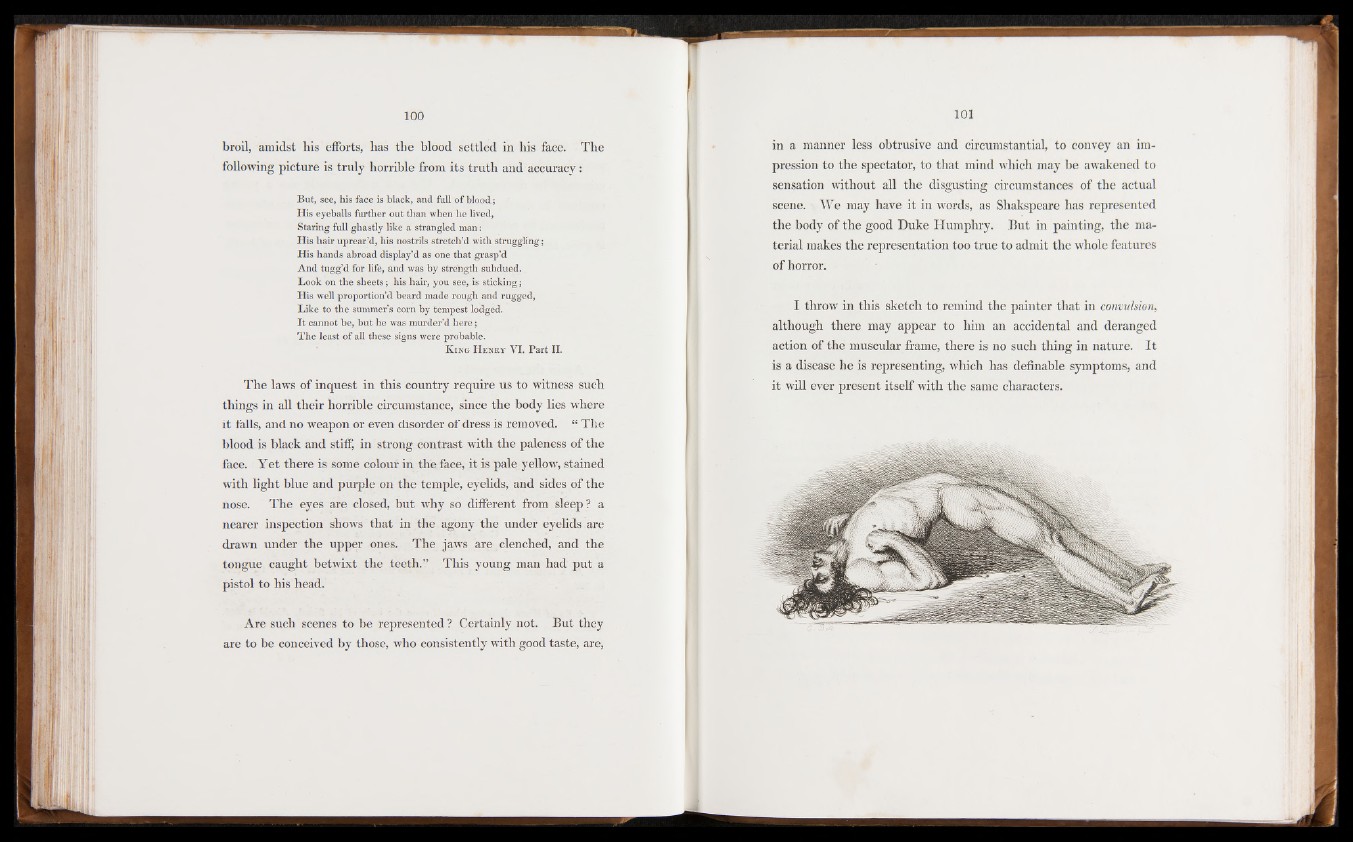

I throw in this sketch to remind the painter that in convulsion,

although there may appear to him an accidental and deranged

action of the muscular frame, there is no such thing in nature. It

is a disease he is representing, which has definable symptoms, and

it will ever present itself with the same characters.