to the angle of the mouth and the upper lip. Hence the lateral

drawing of the lips, the elevation of the upper lip disclosing the

teeth, the very peculiar elevation of the nostrils without their being

expanded (for we breathe only through the mouth in laughing);

hence too the dimple in the cheek, where the acting muscles congregate;

and hence the fulness of the cheek, rising so as to conceal

the eye and throw wrinkles about the lower eyelids and the

temples, whilst the skin of the chin is drawn tight by the retraction

of the cheeks and the opening of the jaws. Thus it is

obvious that the whole moveable features are raised upwards. The

orbicular muscles of the eyelids do not partake of the relaxation of

the mouth; they are excited so as to contract the eyelids and sink

the eye, whilst the struggle of a voluntary effort of the muscles to

open the eyelids and raise the eyebrow gives a twinkle to the eye

and a peculiar obliquity to the eyebrow, the outer part of it being

most elevated.

I have stated that it is the nerve I call respiratory which produces

all this extended influence upon the features, and that with

the loss of the power of that nerve there is a total extinction of

this expression. We have a confirmation of this in witnessing the

further influence of the passion in agitating the whole extent of

the respiratory nerves and muscles. He holds his sides to control

the contractions of the muscles of the ribs. The diaphragm is

violently shaken. The same influence spreads to the throat, and

the sound of laughter is as distinct and peculiar as the signs in

the face.

Defining laughter according to the anatomy, it is a certain influence

of the respiratory nerve of the face, which produces relaxation

of the orbicular muscle of the lip, whilst it excites the class

of ringentes, and the orbicular muscles of the eyelids into action.

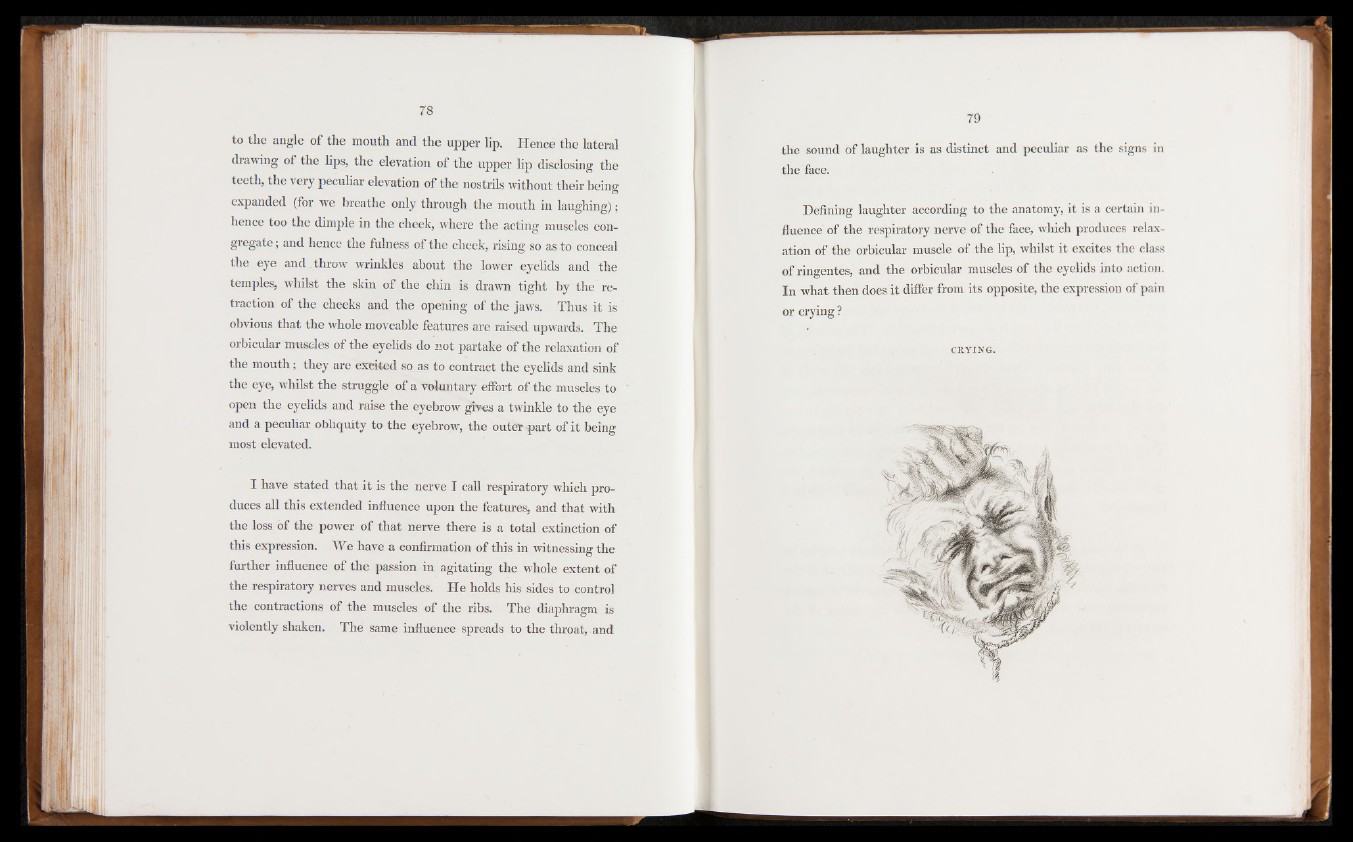

In what then does it differ from its opposite, the expression of pain

or crying ?

CRYING.