of the Negro, when compared with the perfect cranium of a

European, has less of capacity on the fore part.

Having found the reason assigned for instituting a comparison

between the area of the brain-case and that of the bones of the

face quite unsatisfactory; and that in the Negro the whole of the

face is actually smaller, instead of being greater, when compared

with the brain-case, than that of the European ; I was led to compare

the bones of the face with each other: and the conclusion to

which this led me is, that some principle must be sought for, not

yet acknowledged, which shall apply not to the form of the whole

head merely, but to the individual parts also. This principle is,

I imagine, to be found in the form of the face as bearing relation

to the organs; not to the organs of the senses merely, but to those

of all the functions performed by the parts contained in or attached

to the face—the organs of mastication, the organs of speech, the

organs of expression, as well as those which belong to the senses.

And here it is to be observed, that there is not necessarily a deformity

because the feature resembles that of a brute; but in our

secret thoughts the form has reference to the function; and if the

function be allied to intellect, if the organ serves an office connected

with mind (as the eye in particular does), then it is compatible

with the human countenance, though it should bear resemblance

to the same organs in a brute; whereas a form which has

relation to the strength of the jaws, or to a form of the teeth peculiarly

appropriated to the meaner necessities of the animal creation,

is incompatible, and altogether at variance with human physio-

gnomy.

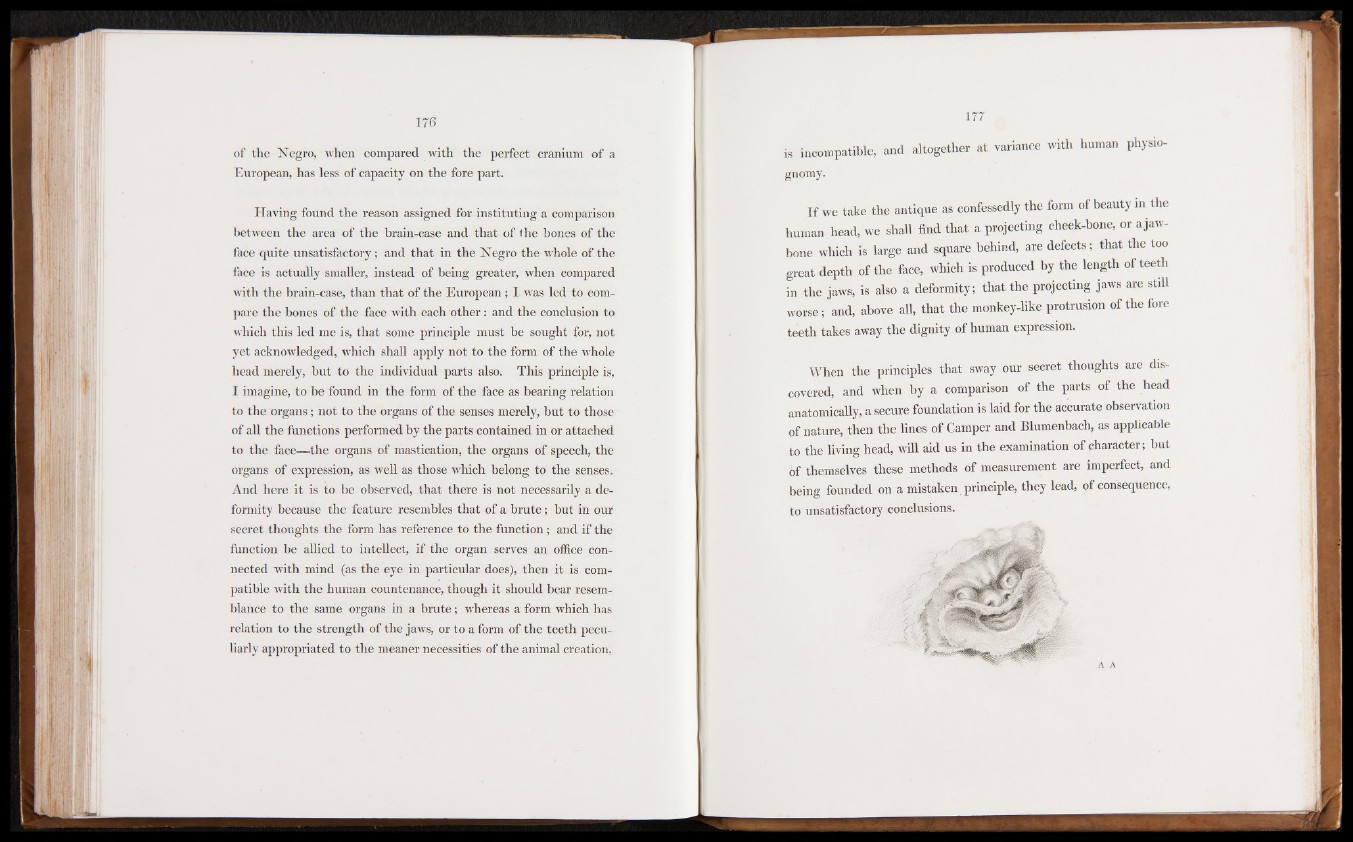

If we take the antique as confessedly the form of beauty in the

human head, we shall find that a projecting cheek-bone, or ajaw-

bone which is large and square behind, are defects; that the too

great depth of the face, which is produced by the length of teeth

in the jaws, is also a deformity; that the projecting jaws are still

worse; and, above all, that the monkey-like protrusion of the fore

teeth takes away the dignity of human expression.

When the principles that sway our secret thoughts are discovered,

and when by a comparison of the parts of the head

anatomically, a secure foundation is laid for the accurate observation

of nature, then the lines of Camper and Blumenbach, as applicable

to the living head, will aid us in the examination of character; but

of themselves these methods of measurement are imperfect, and

being founded on a mistaken principle, they lead, of consequence,

to unsatisfactory conclusions.

A A