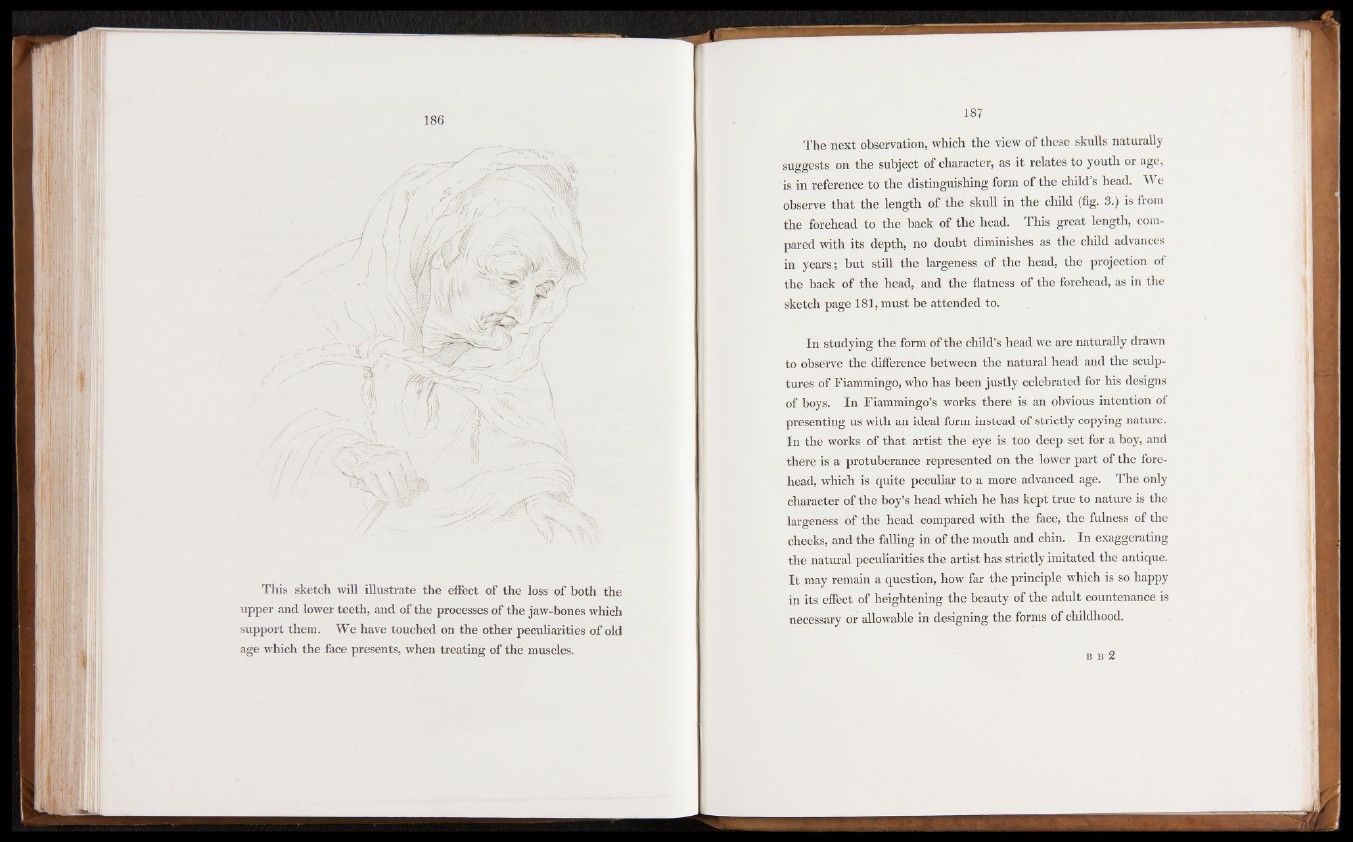

This sketch will illustrate the effect of the loss of both the

upper and lower teeth, and of the processes of the jaw-bones which

support them. We have touched on the other peculiarities of old

age which the face presents, when treating of the muscles.

The next observation, which the view of these skulls naturally

suggests on the subject of character, as it relates to youth or age,

is in reference to the distinguishing form of the child’s head. We

observe that the length of the skull in the child (fig. 3.) is from

the forehead to the back of the head. This great length, compared

with its depth, no doubt diminishes as the child advances

in years; but still the largeness of the head, the projection of

the back of the head, and the flatness of the forehead, as in the

sketch page 181, must be attended to.

In studying the form of the child’s head we are naturally drawn

to observe the difference between the natural head and the sculptures

of Fiammingo, who has been justly celebrated for his designs

of boys. In Fiammingo’s works there is an obvious intention of

presenting us with an ideal form instead of strictly copying nature.

In the works of that artist the eye is too deep set for a boy, and

there is a protuberance represented on the lower part of the forehead,

which is quite peculiar to a more advanced age. The only

character of the boy’s head which he has kept true to nature is the

largeness of the head compared with the face, the fulness of the

cheeks, and the falling in of the mouth and chin. In exaggerating

the natural peculiarities the artist has strictly imitated the antique.

It may remain a question, how far the principle which is so happy

in its effect of heightening the beauty of the adult countenance is

necessary or allowable in designing the forms of childhood.

b b 2