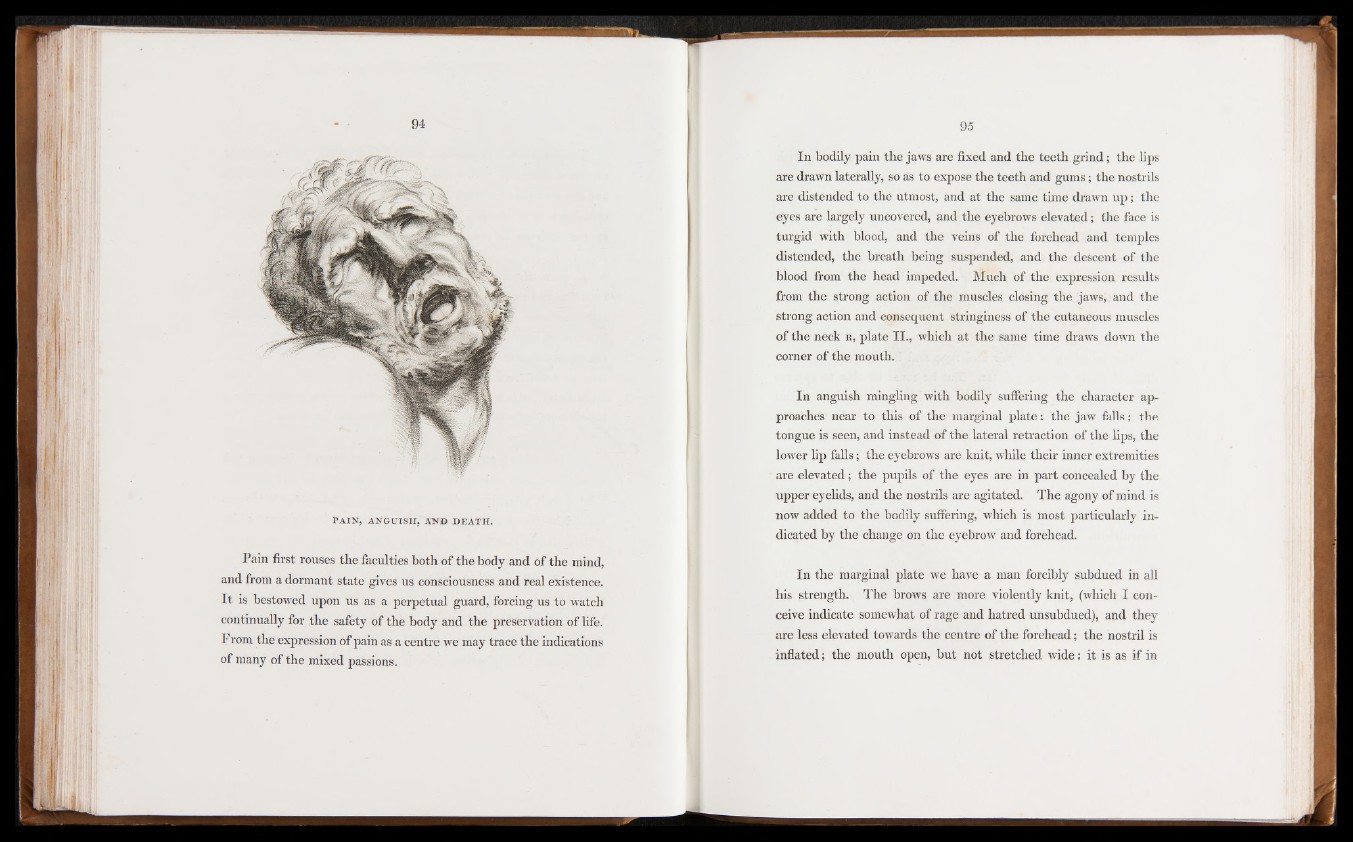

PA IN , ANGUISH, AND DEATH.

Pain first rouses the faculties both of the body and of the mind,

and from a dormant state gives us consciousness and real existence.

It is bestowed upon us as a perpetual guard, forcing us to watch

continually for the safety of the body and the preservation of life.

From the expression of pain as a centre we may trace the indications

of many of the mixed passions.

In bodily pain the jaws are fixed and the teeth grind; the lips

are drawn laterally, so as to expose the teeth and gums; the nostrils

are distended to the utmost, and at the same time drawn up; the

eyes are largely uncovered, and the eyebrows elevated; the face is

turgid with blood, and the veins of the forehead and temples

distended, the breath being suspended, and the descent of the

blood from the head impeded. Much of the expression results

from the strong action of the muscles closing the jaws, and the

strong action and consequent stringiness of the cutaneous muscles

of the neck r , plate II., which at the same time draws down the

corner of the mouth.

In anguish mingling with bodily suffering the character approaches

near to this of the marginal plate: the jaw falls; the

tongue is seen, and instead of the lateral retraction of the lips, the

lower lip falls; the eyebrows are knit, while their inner extremities

are elevated; the pupils of the eyes are in part concealed by the

upper eyelids, and the nostrils are agitated. The agony of mind is

now added to the bodily suffering, which is most particularly indicated

by the change on the eyebrow and forehead.

In the marginal plate we have a man forcibly subdued in all

his strength. The brows are more violently knit, (which I conceive

indicate somewhat of rage and hatred unsubdued), and they

are less elevated towards the centre of the forehead; the nostril is

inflated; the mouth open, but not stretched wide: it is as if in