We travelled over a plain of boundless extent, producing much

crrass, in some places, and a few bushes of Tarchonanthw and Rhi-

gozum. The soil seemed excellent, and capable of producing abundance

of corn; if managed with due attention to the rainy season :

it had the appearance of good loam, but was rather a mixture of

clay and sand. At this time, all the grass, though still standing,

was completely dried up like h ay ; and if it had been set on lire,

the conflagration would have spread with the greatest rapidity over

the plain.

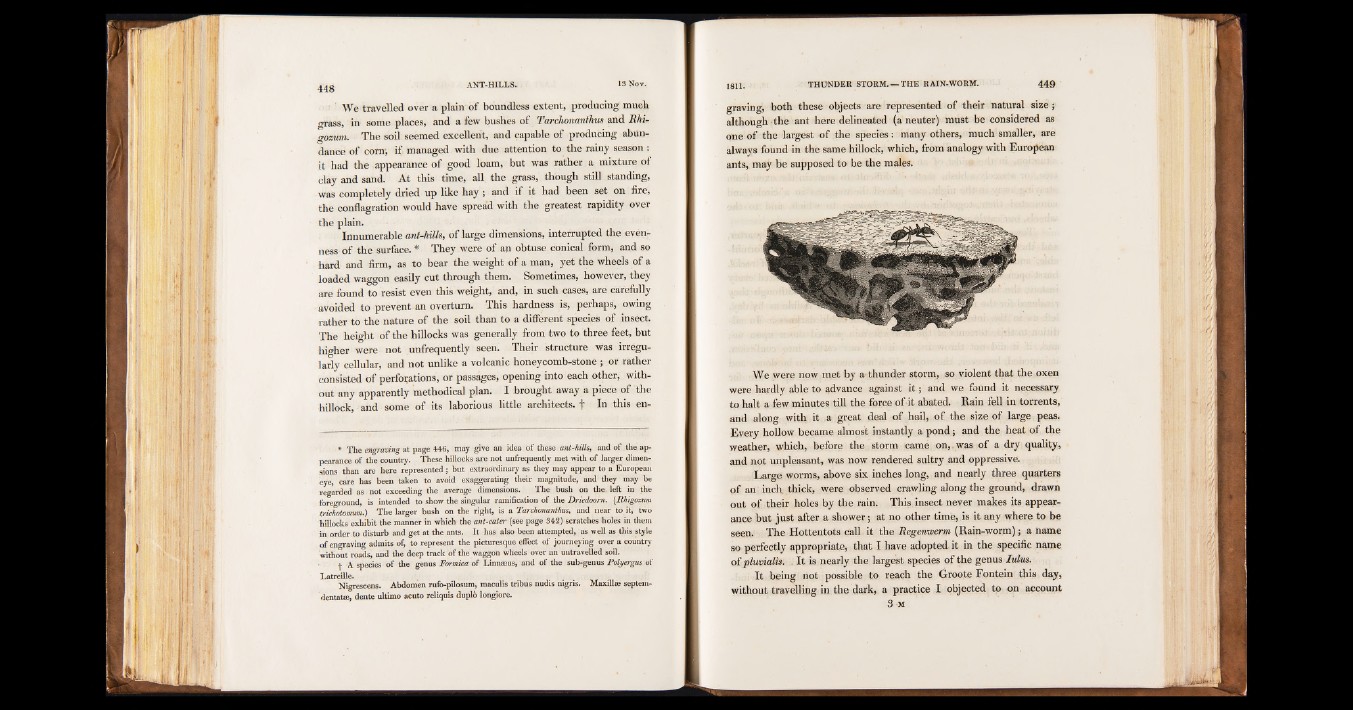

Innumerable ant-hills, of large dimensions, interrupted the evenness

of the surface. * They were of ap obtuse conical form, and so

hard and firm, as to bear the weight of a man, yet the wheels of a

loaded waggon easily cut through them. Sometimes, however, they

are found to resist even this weight, and, in such cases, are carefully

avoided to prevent an overturn. This hardness is, perhaps, owing

rather to the nature of the soil than to a different species of insect.

The height of the hillocks was generally from two to three feet, but

higher were not unfrequently seen. Their structure was irregularly

cellular, and not unlike a volcanic honeycomb-stone; or rather

consisted of perforations, or passages, opening into each other, without

any apparently methodical plan. I brought away a piece of the

hillock, and some of its laborious little architects, f In this en*

The engraving at page 446, may give an idea of these ant-hills, and of the appearance

of the country. These hillocks are not unfrequently met with of larger dimensions

than are here represented ; but extraordinary as they may appear to a European

eye, care has been taken to avoid exaggerating their magnitude, and they may be

regarded as not exceeding the average dimensions. The bush on the. left in the

foreground, is intended to show the singular ramification of the Drieioom. (Rhigozum

trichotomum.) The larger bush on the right, is a Tarchonanthus, and near to it, two

hillocks exhibit the manner in which the ant-eater (see page 342) scratches holes in them

in order to disturb and get at the ants. I t has also been attempted, as well as this style

of engraving admits of, to represent the picturesque effect of journeying over a country

without roads, and the deep track of the waggon wheels over an uutravelled soil.

f A species of the genus Formica of Linnams, and of the snb-genus Polyergus of

Latreille. _ . . . ' V ;

Nigrescens. Abdomen rufo-pilosum, maculis tribus nudis nigris. Maxilla- septem-

dentatse, dente ultimo acuto reliquis duplo longiore.

graving, both these objects are represented of their natural size ;

although the ant here delineated (a neuter) must be considered as

one of the largest of the species: many others, much smaller, are

always found in the same hillock, which, from analogy with European

ants, may be supposed to be the males.

We were now met by a-thunder storm, so violent that the oxen

were hardly able to advance against i t ; and we found it necessary

to halt a few minutes till the force of-it abated. Rain fell in torrents,

and along with it a great deal of hail, of the size of large peas.

Every hollow became almost instantly a pond; and the heat of the

weather, which, before the storm came on,, was of a dry quality,

and not unpleasant, was now rendered sultry and oppressive.

Large worms, above six inches long, and nearly three quarters

of an inch, thick, were observed crawling along the ground, drawn

out of their holes by the rain. This insect never makes its appearance

but just after a shower; at no other time, is it any where to be

seen. The Hottentots call it the Regenwerm (Rain-worm); a name

so perfectly appropriate, that I have adopted it in the specific name

of pluvialis. . It is nearly the largest species of the genus lulus.

It being not possible to reach the Groote Fontein this day,

without travelling in the dark, a practice I objected to on account

3 M