more of the Bokkeveld Karro was seen, the hills intercepting it from

our sight.

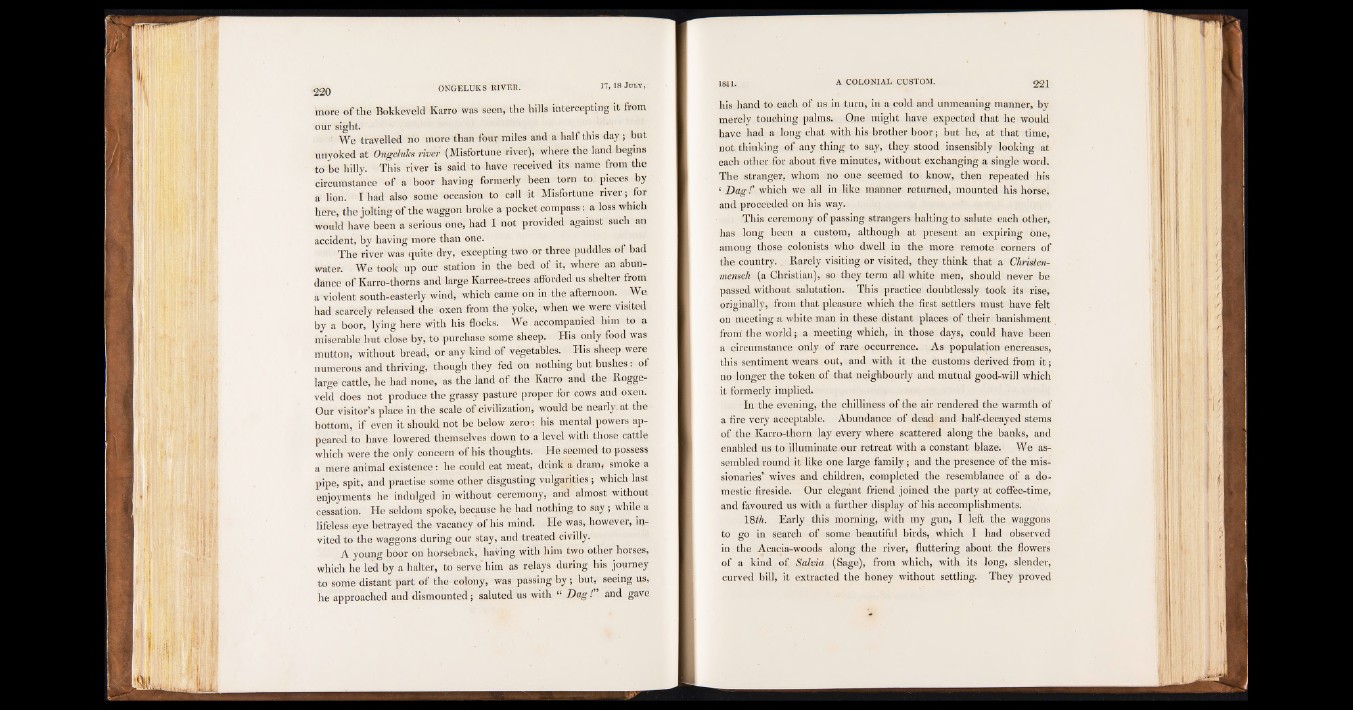

We travelled no more than four miles and a half this day; but

unyoked at Ongelulcs river (Misfortune river),, where the land begins

to be hilly. This river is said to have received its name from the

circumstance of a boor having formerly been torn to. pieces by

a lion. I had also some occasion to call it Misfortune river; for

here, the jolting of the waggon broke a pocket compass: a loss which

Would have been a serious one, had I not provided against such an

accident, by having more than one.

The river was quite dry, excepting two or three puddles of bad

water. We took up our station in the bed of it, where an abundance

of Karro-thorns and large Karree-trees afforded us shelter from

a violent south-easterly wind, which came on in the afternoon. We.

had scarcely released the oxen from the yoke, when we were visited

by a boor, lying here with his flocks. We accompanied him to a

miserable but close by, to purchase some sheep. His only food was

mutton, without bread, or any kind of vegetables. His sheep were

numerous and thriving, though they fed on nothing but bushes: of

large cattle, he had none, as the land of the Karro and the Rogge-

veld does not produce the grassy pasture proper for cows and oxen.

Our visitor’s place in the scale of civilization, would be nearly, at the

bottom, if even it should not be below zero-: his mental powers appeared

to have lowered themselves down to a level with those cattle

which were the only concern of his thoughts. He seemed to possess

a mere animal existence: he could eat meat, drink a drain, smoke a

pipe, spit, and practise some other disgusting vulgarities; which last

enjoyments he indulged in without ceremony, and almost without

cessation. He seldom spoke, because he had nothing, to say; while a

lifeless eye betrayed the vacancy of his mind. He was, however, invited

to the waggons during our stay, and treated civilly.

A young boor on horseback, having with him two other horses,

which he led by a halter, to serve him as relays during his journey

to some distant part of the colony, was passing by; but, seeing us,

he approached and dismounted; saluted us with “ D a g and gave

his hand to each of us in turn, in a cold and unmeaning manner, by

merely touching palms. One might have expected that he would

have had a long chat with his brother boor; but he, at that time;

not thinking of any thing to say, they stood insensibly looking at

each other for about five minutes, without exchanging a single word.

The stranger, whom no one seemed to know, then repeated his

1 Dag!’ which we all in like manner returned, mounted his horse,

and proceeded on his way.

This ceremony of passing strangers halting to salute each other,

has long been a custom, although at present an expiring one,

among those colonists who dwell in the more remote corners of

the country. . Rarely visiting or visited, they think that a Christen-

mensch (a Christian), so they term all white men, should never be

passed without salutation. This -practice doubtlessly took its rise,

originally, from that pleasure which the first settlers must have felt

on meeting a white man in these distant places of their banishment

from the world; a meeting which, in those days, could have been

a circumstance only of rare occurrence. As population encreases,

this sentiment wears out, and with it the customs derived from i t ;

no longer the token of that neighbourly and mutual good-will which

it formerly implied.

In the evening, the chilliness of the air rendered the warmth of

a fire very acceptable. Abundance of dead and half-decayed stems

of the Karro-thorn lay every where scattered along the banks, and

enabled us to illuminate.our retreat with a constant blaze. We assembled

round it like one large family; and the presence of the missionaries’

wives and children, completed the resemblance of a domestic

fireside. Our elegant friend joined the party at coffee-time,

and favoured us with a further display of his accomplishments.

18th. Early this morning, with my gun, I left the waggons

to go in search of some beautiful birds, which I had observed

in the Acacia-woods along the river, fluttering about the flowers

of a kind of. Salvia (Sage), from which, with its long, slender,

curved bill, it extracted the honey without settling. They proved