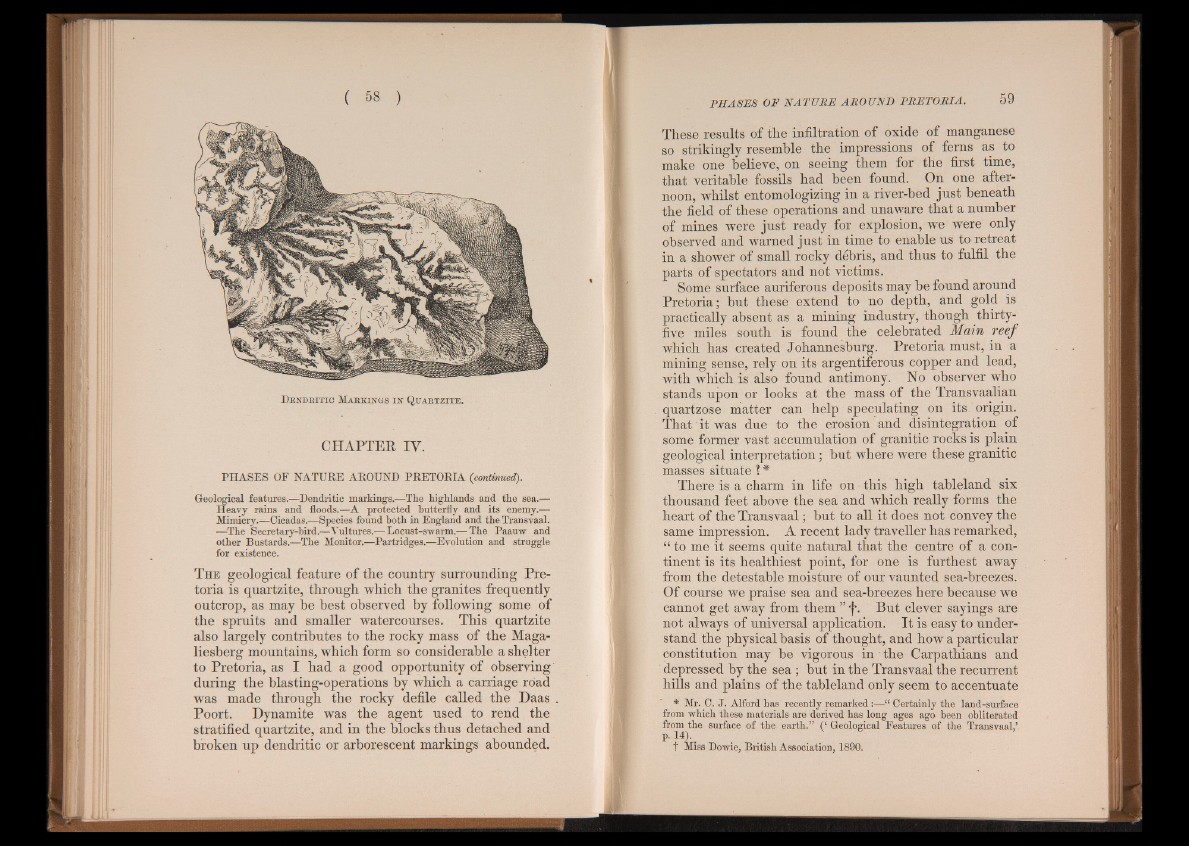

Dendbitic Ma sk in g s in Qu abtzite.

CHAPTER IV.

PHASES OF NATURE AROUND PRETORIA (continued).

Geological features.—Dendritic markings.—The highlands and the sea.—

Heavy rains and floods.—A protected butterfly and its enemy.—

Mimicry.^Cicadas.—Species found both in England and the Transvaal.

*—The Secretary-bird.—Vultures.— Locust-swarm.— The Paauw and

other Bustards.—The Monitor.—Partridges.—Evolution and struggle

for existence.

The geological feature of the country surrounding Pretoria

is quartzite, through which the granites frequently

outcrop, as may he best observed by following some of

the spruits and smaller watercourses. This quartzite

also largely contributes to the rocky mass of the Maga-

liesberg mountains, which form so considerable a shelter

to Pretoria, as I had a good opportunity of observing

during the blasting-operations by which a carriage road

was made through the rocky defile called the Daas

Poort. Dynamite was the agent used to rend the

stratified quartzite, and in the blocks thus detached and

broken up dendritic or arborescent markings abounded.

These results of the infiltration of oxide of manganese

so strikingly resemble the impressions of ferns as to

make one believe, on seeing them for the first time,

that veritable fossils had been found. On one afternoon,

whilst entomologizing in a river-bed just beneath

the field of these operations and unaware that a number

of mines were just ready for explosion, we were only

observed and warned just in time to enable us to retreat

in a shower of small rocky debris, and thus to fulfil the

parts of spectators and not victims.

Some surface auriferous deposits may be found around

Pretoria; but these extend to no depth, and gold is

practically absent as a mining industry, though thirty-

five miles south is found the celebrated Main reef

which has created Johannesburg. Pretoria must, in a

mining sense, rely on its argentiferous copper and lead,

with which is also found antimony. No observer who

stands upon or looks at the mass of the Transvaalian

quartzose matter can help speculating on its origin.

That it was due to the erosion and disintegration of

some former vast accumulation of granitic rocks is plain

geological interpretation; but where were these granitic

masses situate % *

There is a charm in life on this high tableland six

thousand feet above the sea and which really forms the

heart of the Transvaal; but to all it does not convey the

same impression. A recent lady traveller has remarked,

“ to me it seems quite natural that the centre of a continent

is its healthiest point, for one is furthest away

from the detestable moisture of our vaunted sea-breezes.

Of course we praise sea and sea-breezes here because we

cannot get away from them ” j*. But clever sayings are

not always of universal application. It is easy to understand

the physical basis of thought, and how a particular

constitution may be vigorous in the Carpathians and

depressed by the sea ; but in the Transvaal the recurrent

hills and plains of the tableland only seem to accentuate

* Mr. C. J. Alford has recently remarked:—“ Certainly the land-surface

from which these materials are derived has long ages ago been obliterated

from the surface of the earth.” (‘ Geological Features of the Transvaal,’

p-14h. t Miss Dowie, British Association, 1890.