ground, and when they alighted they would wholly disappear

amidst the high grass.

During my sojourn in Angoni-land slavery was in full

swing, but in Chikuse’s town there were very few slaves

ready for transportation. Probably this was due to the fact

that it was the time of the king’s raid into the Shiri valley.

Literally on every hand evidences of the slave trade could

be seen, but in this instance I refer to the export, or rather

the east coast trade, the home traffic being of quite a

different character.

The latter branch of the business was exceedingly lively.

A caravan of three hundred and fifty, all told, left a town

a short distance to the north of Chikuse’s, and preparations

were being made when I left for the dispatch of

another.

Every village shows the familiar sight of the slave in

the yoke. After purchase the poor things are taken to the

headquarters of the east coast traders—nazaras, as the

people call the Zanzibar agents—some of whom are constantly

in this district. Two I can mention by name, Xuala

and Saide.

At the agents the yoke is made secure, and it is not

exaggeration to say that it is often allowed to remain upon

a slave for nine months or a year, night and day, without

being once taken off. Constant rubbing by the yoke upon

the neck chafes the skin, and gradually ugly wounds begin

to fester under the burning sunshine.

Slaves, however, are to some extent looked after with a

view to prevent serious bodily injury, the appearance of

which would certainly depreciate their marketable value.

Until all is ready for a start the miserable slave sits

waiting with all the compulsory and hopeless patience of

bondage. Day after day he sees the sun rise and set. The

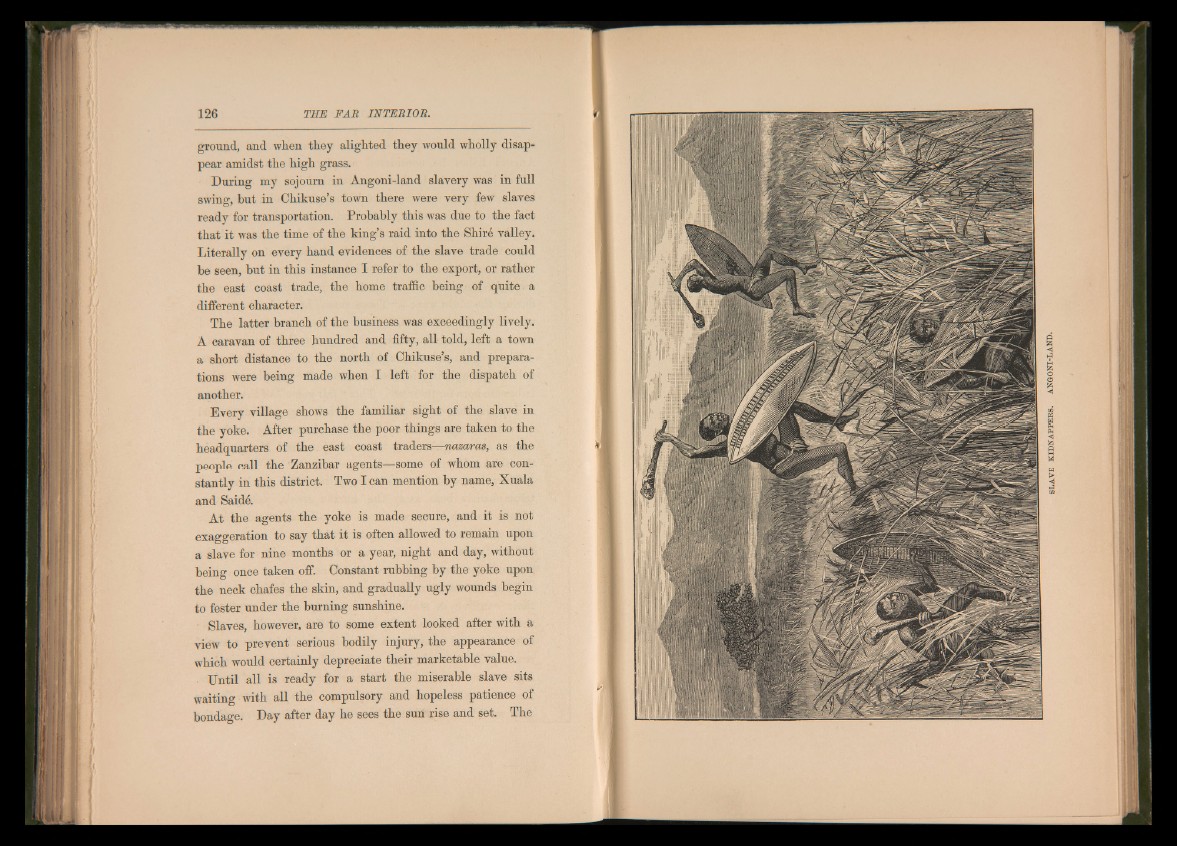

SLAVE KIDNAPPEES. ANGONI-]