shapes and forms, and it was very evident from the prevailing

signs that there would soon he a grand beer-drinking

bout.

John had been out that morning and had killed a magnificent

eland bull with the finest head I ever saw.

The king’s boys took possession of the hut which my

Inyota men had occupied, who therefore, being turned out,

formed a large circle of fires in front of my hut. Shortly

after our arrival crowds of people assembled in what X have

termed the plaza—that is to say the open space in the centre

of the town, between the hut in which I was quartered and

the house of Senhor Eubero. Numbers of drums were

placed in a row. The feast had evidently begun.

John said that the Inyota or Makorikori, who had accompanied

us so far, would be sure to remain until the close of

the festivities. One and all the boys seemed beside themselves

with joy at the thought of returning home; for I had

told them that they would all be paid, and might retrace

their steps whenever they wished to do so. Enlivened by

this happy news, they threw themselves heart and soul into

the convivialities of the hour. Native beer flowed like

running water, and koodoo and eland meat were to.be had

in abundance, for quantities which John and myself had

shot had been dried in the sun.

The open centre of the town swarmed with ebonised

humanity. Sounds of song and jubilant shouts mingled

with the throbbing vibrations of the everlasting drum,

breaking with droll and savage harmonies the natural

stillness of the forest air. The noise rose and fell like

Tnlling waves of sound, or like the spasmodic drone of a

rising gale.

Dark-skinned maidens danced merrily and sang their

shrillest notes, keeping time as they stamped the ground,

throwing their bodies alternately right and left, and following

each other through the snake-like windings of their

frolicsome fandango. With more solemnity the older

women, bearing upon their backs the young ones, whose

little heads would wag in every way, as if they were fixed

on the universal joint principle, while their mothers with

great flat feet entered upon the dance with a serious

earnestness of purpose.

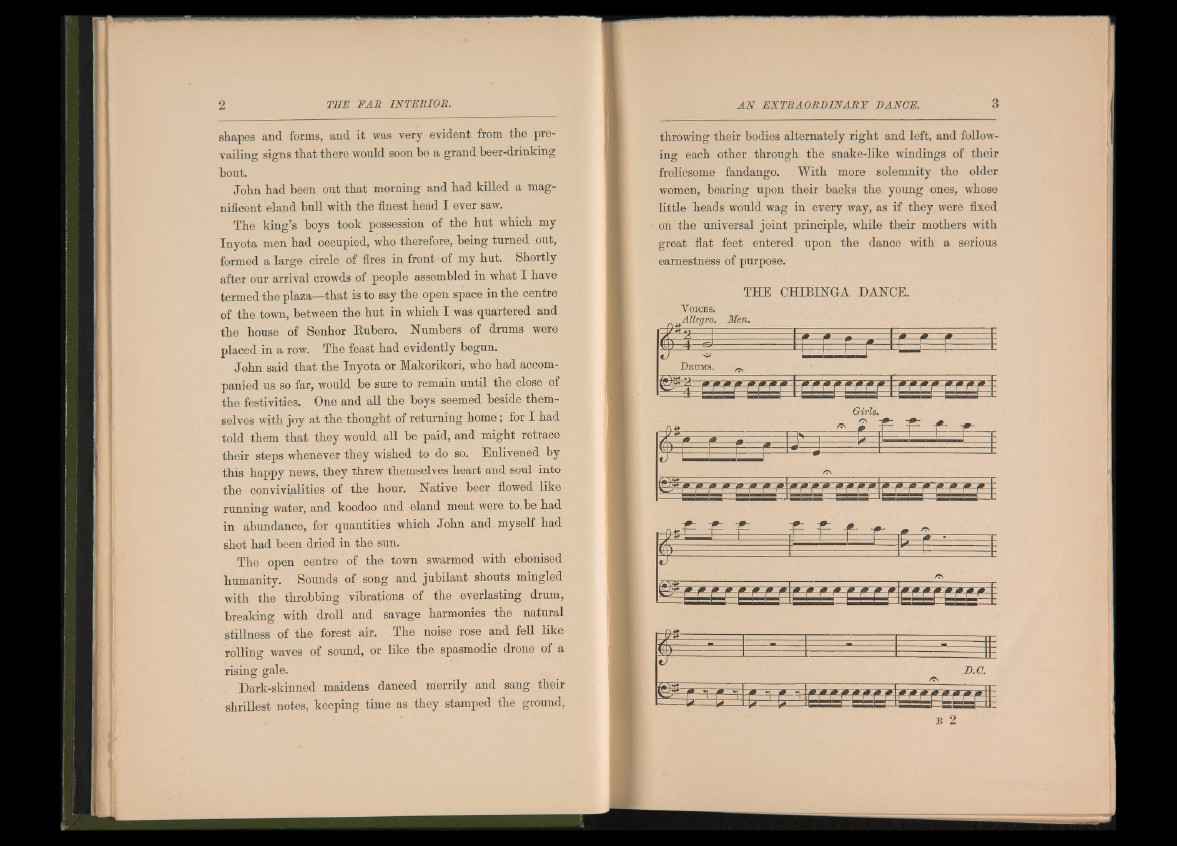

THE CHIBINGA DANCE.

V o ic e s .

Allegro. Men.

f ..

D b u m s .

Í

Girls. m £-0m-. --t0—- -mF-

... 0 ?

-0- -0- -0-

tz—ÍZ--------- ti—1 ri—1— f1-=— -i—r .* = £— ____ = — i—=--------------

/TS

I