My mind was busy with thoughts that at this juncture

some of the party, which had lingered far in the rear, would

inevitably pass the man whom I had left with orders to

stop them. Should that happen, and if they innocently

made the slightest noise they would soon attract the

attention of the wild Makanga.

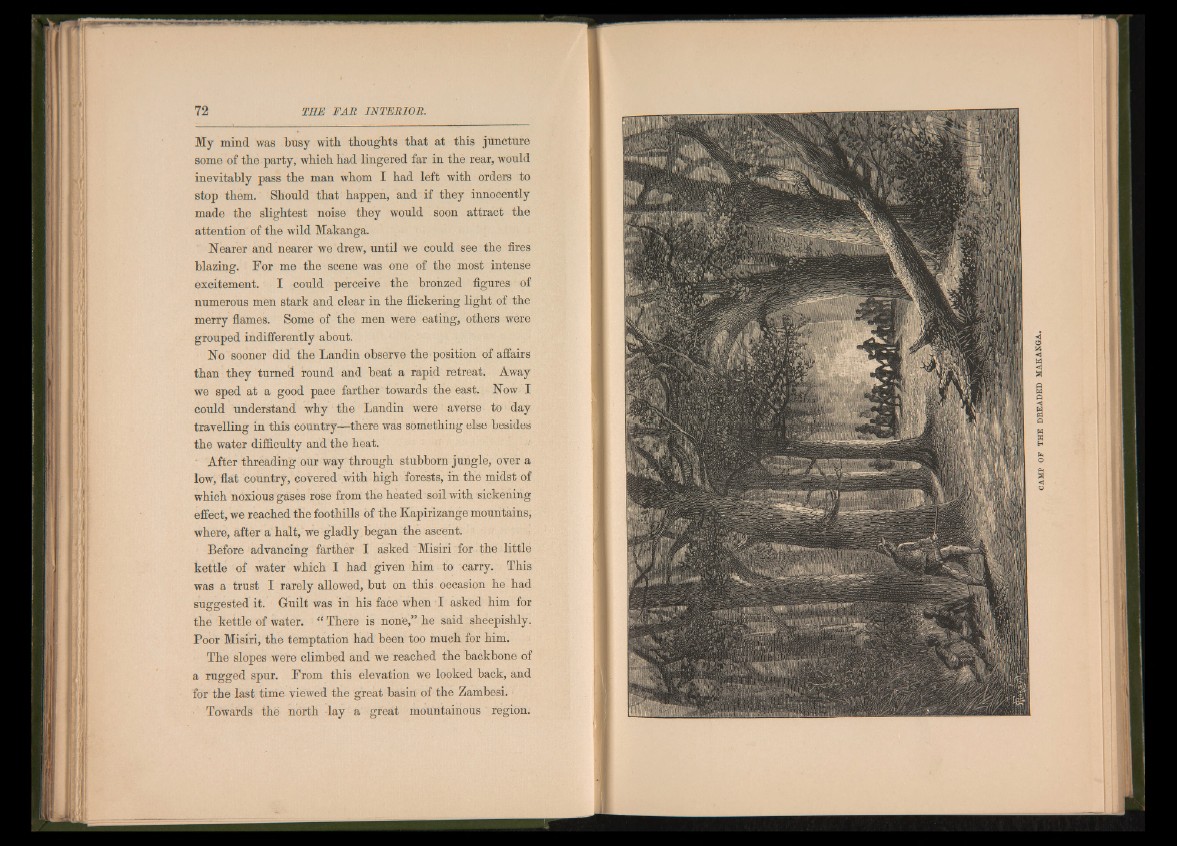

Nearer and nearer we drew, until we could see the fires

blazing. For me the scene was one of the most intense

excitement. I could perceive the bronzed figures of

numerous men stark and clear in the flickering light of the

merry flames. Some of the men were eating, others were

grouped indifferently about.

No sooner did the Landin observe the position of affairs

than they turned round and beat a rapid retreat. Away

we sped at a good pace farther towards the east. Now I

could understand why the Landin were averse to day

travelling in this country—there was something else besides

the water difficulty and the heat.

After threading our way through stubborn jungle, over a

low, flat country, covered with high forests, in the midst of

which noxious gases rose from the heated soil with sickening

effect, we reached the foothills of the Kapirizange mountains,

where, after a halt, we gladly began the ascent.

Before advancing farther I asked Misiri for the little

kettle of water which I had given him to carry. This

was a trust I rarely allowed, but on this occasion he had

suggested it. Guilt was in his face when I asked him for

the kettle of water. “ There is none,” he said sheepishly.

Poor Misiri, the temptation had been too much for him.

The slopes were climbed and we reached the backbone of

a rugged spur. From this elevation we looked back, and

for the last time viewed the great basin of the Zambesi.

Towards the north lay a great mountainous region.

CAMP OF THE DREADED MAKAKGA.