tv* .n fiM

Genus MERULA.

Gen. Char. Bill nearly as long as the head; straight at the base; slightly bending towards

the point, which is rather compressed; the upper mandible emarginated; gape furnished

with a few bristles. Nostrils basal, lateral and oval, partly covered by a naked membrane.

Legs o f mean length, muscular. Toes, three before and one behind; the outer toe joined

at its base to the middle one, which is shorter than the tarsus. Claws slightly arcuate;

that of the hind toe the largest. Of the wings, the first quill is short, and the third and

fourth are the longest.

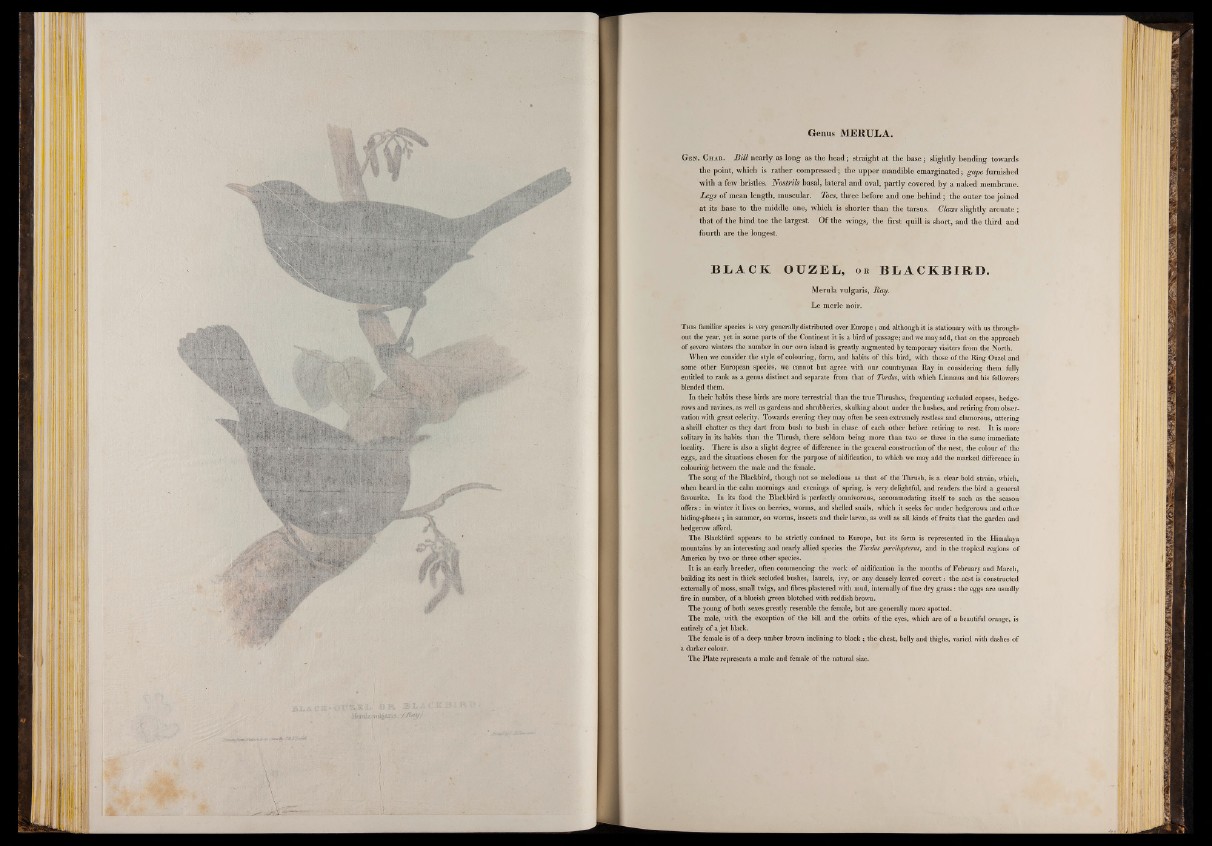

B L A C K OUZEL, o k B L A C K B IR D .

Merula vulgaris, Ray.

Le merle noir.

T h is familiar species is very generally distributed over Europe; and although it is stationary with us throughout

the year, yet in some parts of the Continent it is a bird of passage; and we may add, that on the approach

of severe winters the number in our own island is greatly augmented by temporary visiters from the North.

When we consider the style of colouring, form, and habits of this bird, with those of the Ring Ouzel and

some other European species, we cannot but agree with our countryman Ray in considering them fully

entitled to rank as a genus distinct and separate from that of Turdus, with which Linnaeus and his followers

blended them.

In their habits these birds are more terrestrial than the true Thrushes, frequenting secluded copses, hedgerows

and ravines, as well as gardens and shrubberies, skulking about under the bushes, and retiring from observation

with great celerity. Towards evening they may often be seen extremely restless and clamorous, uttering

a shrill chatter as they dart from bush to bush in chase of each other before retiring to rest. It is more

solitary in its habits than the Thrush, there seldom being more than two or three in the same immediate

locality. There is also a slight degree of difference in the general construction of the nest, the colour of the

eggs, and the situations chosen for the purpose of nidification, to which we may add the marked difference in

colouring between the male and the female.

The song of the Blackbird, though not so melodious as that of the Thrush, is a clear bold strain, which,

when heard in the calm mornings and evenings of spring, is very delightful, and renders the bird a general

favourite. In its food the Blackbird is perfectly omnivorous, accommodating itself to such as the season

offers : in winter it lives on berries, worms, and shelled snails, which it seeks for under hedgerows and other

hiding-places ; in summer, on worms, insects and their larvae, as well as all kinds of fruits that the garden and

hedgerow afford.

The Blackbird appears to be strictly confined to Europe, but its form is represented in the Himalaya

mountains by an interesting and nearly allied species the Turdus peecilopterus, and in the tropical regions of

Aifierica by two or three other species.

It is an early breeder, often commencing the work of nidification in the months of February and March,

building its nest in thick secluded bushes, laurels, ivy, or any densely leaved covert: the nest is constructed

externally of moss, small twigs, and fibres plastered with mud, internally of fine dry grass: the eggs are usually

five in number, of a blueish green blotched with reddish brown.

The young of both sexes greatly resemble the female, but are generally more spotted.

The male, with the exception of the bill and the orbits of the eyes, which are of a beautiful orange, is

entirely of a jet black.

The female is of a deep umber brown inclining to black ; the chest, belly and thighs, varied with dashes of

a darker colour.

The Plate represents a male and female of the natural size.