I

•lit 1

ATLAS OF AUSTRALIA—1Í

ID tlio north-west part of tlio eclony, Yiintara, Coiiljain, and Salt

Liikos ruceiro tbe woters of a considerable area.. The small amount

of rainfall, wLicb is cbarncterlstic of this ])art of the colony, renders

the liow of I ho crocks intermittent; the lakes, therefore, become

reduced to raere marsJies during seasons of drought, and only appear

as sheets of water when floods occur.

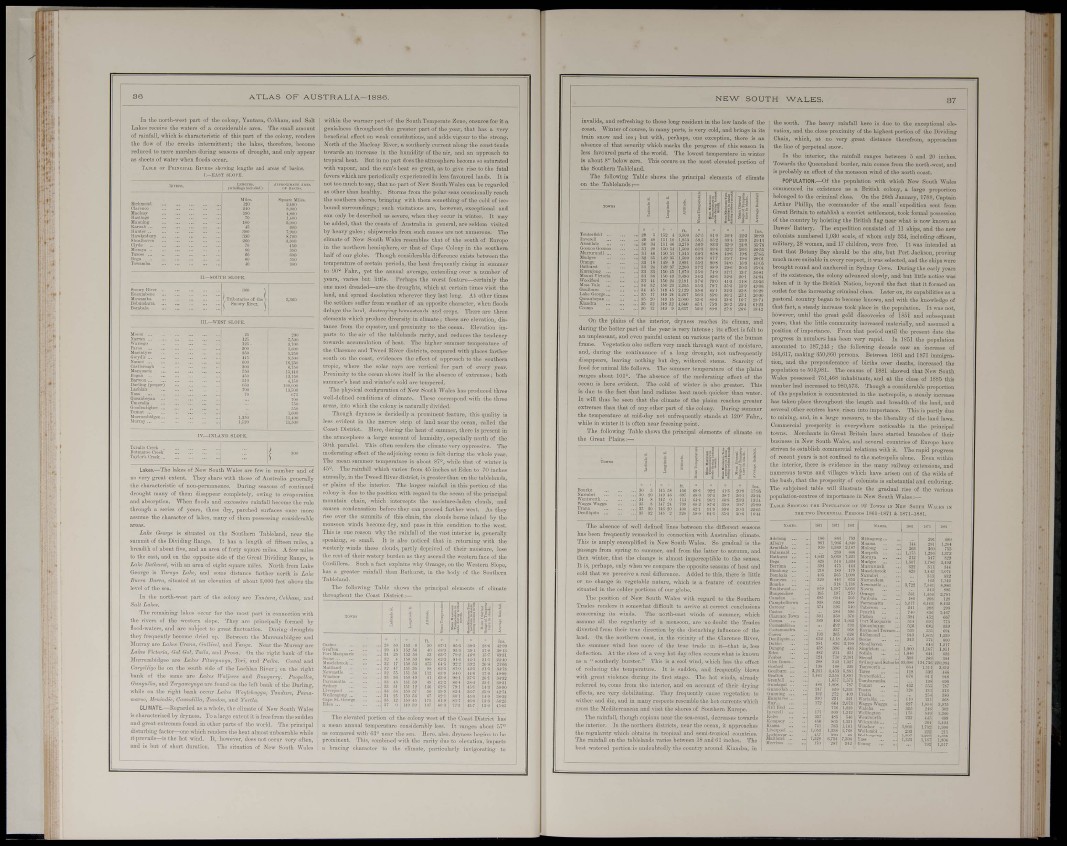

TAULS OF 1'iiixcii.Ai. UivKita showitiit longtlis nn,! nroas of I)«!»?.

Hiiwkwirao-

CIjTk. ..

MiiniTO ..

II.-SODTH SI-OPJ

Qucanbcyaii ...

OrvxlmlffhiK !!!

Tflylor'8 I

Lakes.—Tho lakes of New South Wales are few in nnmber and of

no very great extent. 'ITiey share with those of Australia genei-ally

the characteristic of non-permanence, During seasons of continued

drought many of thom disappear completely, owing to evaporation

and absorption. Wlicn Hoods and excessive rainfall become tho rule

through a series of years, these dry, parched surfaces ouce more

assume the character of lakes, many of them possessing considerable

L-ilce George is situated on the Southern Tableland, near the

summit of the Dividing Range. It has a length of fifteen miles, a

breadth of about five, and an ai'ea of forty square miles, A few miles

to the east, and on the opposite side of the Great Dividing Range, is

Lnlui Bnlhunl, with an area of eight square miles. North from li^ake

George is Taruga Lake, and some distance farther north is Lnhe

Burra Bnrra, situated at an elevation of about 8,000 feet above the

level of the sea.

I n tbe north-west part of the colony are YanUiru, Colham, and

Soli Lakes.

The i-emaining lakes occur for the most part in connection with

the rivers of tlio western slope. They are principally formed by

flood-waters, and are subject to great fluctuation. During d.-onghts

they frequently become dried up, Betweon the Miirriimbidgee and

Slurray are Lake« Umna, G^dlivet, and Yanfia. Near the Murray ai

Lalvs ViHoria, Ool Go!, Taila, and Pi-non. On the right bank of tl:

iturnimbidgee are Lakes Pitarpmiga, Tori, and I'aika. Coical an

CariiellujoWe on the south side of the Lai-hlan River; on the rig}

bank of the same aro Lakes Waljeers and Bungnrry. Po,/pelh

&Hnyulku, and 'Hryaweynya aro found on tbe left bank of the Darling,

while on the right bank occur Lnkus Woylchuogn, Tandure, Panmmarou,

Menhidie, Catciidilla, T"ud<m, and Yorlln.

CLIMATE.—Rigai-ded as a whole, the climate of Now South Wa](

is characterised by dryness. To alarge extent it is free from tho sudden

and great extremes found in other ¡larts of tho world. The principal

disturbing factor—one which venders the heat ahnost unbearable while

it pit'vails—is the hot wind- It, however, does not occur very often,

and is but of short duration. The situation of Now South Wales

%vithin the >varmer part of tho South Temperat e Kono, onsiiros for it a

genialness thi-oiighout the greater part of the year, that has a very

beneficial effect on weaV constitutions, and adds vigour to the strong.

North of the Macleay River, a sontheriy current along the coast tends

towards an increase in tho humidity of the air, and an approach to

tropical heat. But in no part does the atmosphere became so sutui-ated

with vapour, and the sun's heat so great, as to give rise to the fatal

fevei« which are periodically experienced iii less favoured lands. It is

not too much to say, that no part of Now South Wales can bo regarded

as other than healthy, St-ovms from tho polar seas occasionally reach

the southern shores, bringing with them something of the cold of icebound

surroundings; such visitations are, however, exceptional nnd

can only be described as severe, when they occur in winter. It may

be added, that tho coasts of Australia in general, are seldom visited

by heavy gales; ship w e e k s from such causes are not numerous, Tlie

climate of New South AVales resembles that of the south of Em^opo

in tho northern hemisphere, or that of Capo Colony iu the southern

half of our globe. Though considerable difference exists between tho

tempemture of certain periods, the lieat frequently rising in snmmer

to 00° Fahr,, yet tlie annual average, extending over a number of

years, varies but little. Perhaps the worst feature—certainly the

one most dreaded—are the droughts, which at certain times visit the

land, and spread desolation wherevor they last long. At othor times

the settlers suffer fi'om weather of an opposite character, when floods

deluge tho laud, destroying homesteads and crops. There are three

elements which produce diversity in climate; these are elevation, distance

fi-om tho equator, and proximity to the oceau. Elevation imparts

to the air of the tablelands rarity, and reduces the tendency

towards accumulation of heat. The higher summer temperature of

the Clarence and Tweed River districts, comimred with places farther

south on tho coast, evidences the effect of approach to the southern

tropic, where tho solar rays nre vertical for part of every year.

Proximity to the ocean shows itself in the absence of extremes; both

summer's heat and winter's cold nre tempered.

The physical confignration of New South Wales ha.'i produced three

well-defined conditions of chmate. These corresjiond with tho three

areas, into which tho colony is naturally di\-idod.

Though drj-ness is decidedly a prominent feature, this quality is

less oi-ident in the miri'ow strip of land near the ocean, called the

Coast District, Here, during the heat of summer, there is present in

the atmosphere a large amount of humidity, c.opecially north of the

I yOth parallel. This often renders tlie climate vciy oppressive. The

moderating effect of the adjoining ocean is felt during the whole year.

The mean summer tempei-ature is about 87", while that of winter is

4r>°. Tho rainfall which varies from 45 inches at Eden to 70 inches

annually, in the Tweed River district, is greater than on tho tablelands,

or plains of the interior. The larger rainfall in this portion of the

colony is due to the position with regard to the ocean of the ])rincipal

mountain chain, which intercepts the moisture-laden clouds, and

causes condensation before they can proceed farther west. As they

rise over the summits of this chain, the clonds borne inland by the

monsoon winds become dry, and pass in this condition to the west.

This is one reason why the rainfall of the vast interior is, generally

-•ipeaking, so small. It is also noticed that in returning with the

westerly winds these clouds, partly deprived of their moisture, lose

the rest of thoir watery burden as they ascend the westera face of the

Cordillera, Such a fact exjilains why Orange, on the Western Slopo,

has a greater rainfall than Bathurst, in tho body of the Southoro

Tableland.

The following Tabic shows the principal elements of climate

throughout the Coast District:—

The elevated portion of tho colony west of tho Coast District has

u mean annual tomiieraturo oonsidera}>ly less. It ranges about 57°

ns compared with G3° near tho sen., Hei-e, also, dryness begins to be

prominent. This, combined with the rarity due to elevation, imparts

a bracing character to the climate, particularly invigorating to

N E W SOUTH WALES.

invalids, and refreshing to those long resident in the low lands of the

coast. Winter of course, in many parts, is very cold, and brings in its

train snow and icej but mth, perhaps, one exception, thero is an

absence of tiat severity which marks the progress of this season in

less favoured parts of tho world. The lowest tempei-ature in winter

is about 8° below zoro. This occurs on the most elevated portion of

the Southern Tableland.

The following Table shows the principal elements of climate

on the Tableknds;—

1)11 , drynes

duriiiL' tho hotUir nartcl

au uupiEiisaul, and oven paintui extent on voj-iuus parts of the human

frame. Vegetation also suffers very much through want of moisture,

and, during tho continuance of a long drought, not nnfrequently

disappears, leaving notiing but dry, mthered stems. Scarcity of

food for animal life follows. The summer temperature of the plains

ranges about 101°. The absence of the moderating effect of the

ocean is here evident. The cold of winter is also greater. This

is due to the fact that land radiates heat much quicker than water.

I t will thus be seen that the climate of the plains reaches greater

extremes than that of any other part of the colony. During summer

the temperature at mid-day not nnfrequently stands at 120" Fakr,,

while in winter it is often near freezing point.

The follo^ving Table shows the principal elements of climato on

the Great Plains:-

the south. The heavy rainfall here is duo to the exceptional elevation,

and the close proximity of tho highest portion of the Dividing

Chain, which, at no very great distance therefrom, approaches

the line of perpetual snow.

In the interior, the rainfall ranges between 3 and 20 inches.

Towards the Queensland border, rain comos from the north-west, and

is probably an effect of the monsoon wind of the north coast.

POPULATION,—Of the population with which New South Wales

British colony, a large proportion

On the 2(5th January, 1788, Captain

of the small'expedition sent from

ct settlement, took formal pos.<ies9lon

itish flag near what is now known aa

. consisted of 11 ships, and the new

.gofiico

belonged to the criminal class.

Arthur Phillip, the commander

Great Britain to establish a conv

of the country by hoisting the Bi

Dawes' Battery. The expeditioi

lis, of whom only 334, i:

military, 28 women, and 17 childi-en, were free. It was intended s

iii-st that Botany Bay should be the site, but Port Jackson, proving

much more suitable in every respect, it was selectod, and the ships were

brought round and anchored in Sydney Cove. During the early years

of its existence, the colony advanced slowly, and but little notice was

taken of it by the British Nation, beyond the fact that it formed an

outlet for the increasing criminal class. Later on, its capabihties as a

pastoral country began to become known, and with the knowledge of

that fact, a steady increase took place in tho population. It was not,

however, until tho great gold discoveries of 1851 and subsequent

years, that the little community increased materially, and assumed a

position of importance. From that period until the present date the

progress in nuinbei's has been very rapid. In 1851 tho po)niIation

amounted to 187,243; the folloiving decade saw an increase of

163,017, making 350,860 persons. Between IStll and 1871 immigra,-

tion, and the preponderance of births over deaths, increased tho

population to 003,981, The census of 1881 showed that New South

Wales possessed 751,468 inhabitants, and at the close of 1885 this

number had increased to 980,573. Though a considerable proportion

of the population is concentrated in the metropolis, a steady increase

has taken place throughout tho length and breadth of the land, and

several otJier centres have risen into importance. This is partly duo

to miuing, and, in a large measure, to Che liberality of tho land laws.

Commercial prosperity is everyivhei'e noticeable in the principal

towns, llerchants in Great Britain havo started branches of their

business in New South Wales, and several countries of Europe have

striven to establish commercial relations with it. The rapid progress

of recent years is not confined to the metropolis alone. Even within

the interior, there is evidence in the many railway extensions, and

numerous towns aud rillages which have arisen out of the wiids of

the bush, that the prosperity of colonists is substantial and enduring.

The subjoined table will illustrate the gradual rise of the various

po)iuIation-centres of importance in New South Wales ;

TAULE Snowixo TIN; POPUI.ATIOK OP ¡12 I'owss IK NKW SOUTH W.M.K., ,NTIIETWO

DKCBXXI.II, pKiiions 18Ü1-187I & 1871-1881.

The absence of well defined lines bohveen the different seasons

has been frequently remarked iu connection with Australian climate.

This is amply exemplified in New South Wales. So gradual is the

passage from spring to summer, and from the latter to autumn, and

then winter, that the change is almost imperceptible to tho sens«

I t is, perhaps, only when we compare the opjiosite seasons of heat ami

cold that we percoive a real difference. Added to this, there is litt

or no change in vegetable nature, which is a feature of countri

situated in the colder portions of our globe.

The position of New South Wales with regard to the Southern

Trades renders it somcwhnt difficult to arrive at correct conclusioi

concerning its winds. The north-CBSt winds of siunmer, whit

assume all the regularity of a monsoon, are uo doubt the Trade»

diverted from their true direction by the distui-bing influencs of tho

land. On the noi-thern coast, in the vicinity of the Clarence Bivei-.

the summer wind has more of the true trado m it—that is, le:

doliection. At the closo of a very hot day often occurs what is known

as a " southerly burster." This is a cool wind, which has tho effect

of reducing tho temperature. It is sudden, and frequently blow

m t h greiit violence during its first stage. Tho hot winds, alreadv

refen-ed to, come from the intei-ior, and on account of their di'yin.i'

offects, are very debilitating. Thoy fretjuently cause vegetation t"

witJior and dio, and in many respects resemble the hot currents which

cross the Mcditori-auoau and visit the shores of Southern Europe.

The rainfall, though copious near the sea-coast, decreases towards

the interior. In the northern districts, near tho ocean, it approacho

the regularity which obtains iu tropical and semi-tropicnl countries.

The rainfall on the tablelands varies between 18 and 61 inches. The

best watered portion is undoubtedly the country around Kiandra, in ,

S

s,™,

K r

fiY

- • i

K- ti. ,

it'

J "

«

"" letflii ...

. n'viiniiSubr

ÍSr"":::

TüiittrHcld.,.

„ p .