n ATLAS OF AUSTRALIA—18S6.

DIVISIONS.—As different settlomenU arose on tlie seaboard of Anstralin,

and with tlioni interests wLicli were frequently not identical,

so in tlie conrse of time, tlie necessity for aeparnte governing centres

became endent.

The divisions of Australia with their chief towns aro as follows :—

istmlln, (Vnclutiing tlie

lera lOTitory)

LAN D.—Connected with the soil of Australia, ever since its annexation

by the British Crowu in 1788, there has been an interest which

has iiiauifosted itself iu every phase of society. Perhaps no subject in

the histoiy of tlie colonies has given more ti-ouble and less satisfaction,

in the matter of legislation, for its occupation or alienation. It would

certainly be difficult to point to any other question which has arisen

so often for settlement, each recurrence sliowiug how far from finality

was the last attempt to produce a land law which would mete out equal

justice to all, and leave no opportunity for abase, There is no doubt

that the scarcity iu this respect in Britain, and the low value which

it-s almost unlimited area places upon it iu the colonies, ai-e among the

causes which tend to keep it ever present in the minds of tho great

body of the population. The earth-hunger of the immigiant, accustomed

from his childLood to regard the possession of land as far

beyond his reach, is at once roused when he reaches a country where

the value of land at a minimum, owing to the want of a people to

use it. Millions of acres, now lying idle and waste, travoi-sed by the

aboriginal, and pastured upon by tho kangai-oo and emu (some, indeed,

of the best grazing land that has fallen from the hand of Nature), only

require the teeming thousands of the great cities of the Old World, to

rise, from no value, to prices iu excess of that which obtains at pi-esent

throughout the settled districts of Australw. It is an axiom only too

self-evident, that laud, without a people to own and till it, can have

no value attaching to it. Alter the ciroumstances, by placing upon it

a race which requires it for its support anil pleasiu'e, aud the inherent

desire, and necessity for the use of it, at once create a measure by

which it may be valued. This, it will be found, has obtained in the

histoid of every colonization from the early Phcenician colonies on the

shores of the Mediterranean, to the populating of America and Austi'alia

in modern times by the British race. The tendency to reduce

the extreme coucentration of population in the cities anil tomis of the

Old AVorld, where jjower to exist, for a very large uumbei-, has been

pushed to the verge of possibility, is increasing; aud the advance of

such principles -will have the eifect, ultimately, of peopling a land that

isopentoreoeivethem. ltmay,thei-efore, beexpectedthatthesubject

of land in A\istralia, will ever possess an intei est whicb has ceased to

attach to it, in older countries.

Owiiereliip of laud, in the early days of Australian colonization, was

obtained by means of free grants fi'om the Crowu. In most cases,

the-se were held lightly, and iu very many, the recipients parted with

thoii- easily-acquired rights, for almost nominal ainoimts. The fii-st

grants took place in the neighbourhood of Sydney, and included

part of what is now the metropolis of New South Wales, and the

suburbs of Pyrmont and Balmaiii. Later on, several farms were

granted at Prospect Hill. These free gifts of kinl were made

to persons in various positions in the pioneer colony. Subseiiucintly,

every military ofticer and free settler received a grant of land.

Very hberal occupation rights wore also aUowed to private soldier.":

serving on the Australian penal station, in order to guard the

small colony from the approach of famine, which more than once

threatened its existence. Clorgj-inen wore iucluded among the

recipients of the land-gifts of the State. In this way, some of the best

and most fertile lands in the Illawarra and Uawkesbury districts became

settled upon, and ])laced under cultivation.

In 1813, the (ireat Dividing Range, which had hitherto baffled all

attempts to proceed inland, was successfully ci'osaed by tho enterprising

explorer», Blaxlund, Lawson, and Weutworth, aud subsequently the

' •• upland plains of the En thurst district becami; kuo^vn to the small

colony. L arge g 111 nt.s •

free labour wa.s added in cases where

permanently occupied. ^ Vit hin two

practicable route across the Blue iloi

country weie stocked with sheep an

Bathui-st made its coiuinencemeut at

spo.

During the administration of Sir Th

system, uiuler which land grants wen

manner that lost to tho State some

i-al aud 1 1 lauds

•ly-discovered territory, and

and was entered upon, and

-.5 from the discovery of a

ns, largo areas of the new

:tle. 'I'he present town ot

Australian history.

Brisbane, we ilud that the

d, was manipulated iii a

ids of acres of the best

ia, without any return

whatever. Many obtained these grants of land, who could not show

even the slightest claim, and who never intended to use them. They

simply secured areas, which were great or small, in proportion to their

own inliuenoe, or that of thoir friends, with the governing authorities,

for purposes of speculation. T'he effect of this squandering of the

public lands, in the early days of settlement, on those who held them

for purposes other than occupation, is felt even now iu the neighbmir.

hood of more than one of our inland towns, where the utmost difficulty

is frequently e.\perienced in obtaining even a few acres for a homestead.

Grants, at this time, were also made to companies, in proportion

to the capital introduced. Less objection could be raised against

concessions of this character, but in more than one instance the gift

was on too liberal a scale.

In 1832, a system of public auction was introduced, and a genei al

upset price of Ss. per acre was fixed. During 1S40, it was raised to

12s, per acre. In 1842, in the neighbourhood of Port Phillip, the

minimum rose to iil per acre, and in the following year, it was

increased, generally, to that amount. The subsequent division of

Australia into the different colonies, considerably affected the

alienation of the public lands. T'he dominant principles of different

leaders now became an element in the general result.

In 1829, the colony of Western Australia was founded, and a

settlement commenced on the Swau Hiver. Some of the largest

grants in Australia were made at the initiation of the colony of the

west coast. These gifts of land were in proportion to the labour or

capital introduced into the new settlement. One grant amounted to

the very large area of 07ii million acres.

In 188(>, South Australia was constituted a separate colony, but

in this case a much fairer system was put into practice. The land was

sold at auction, the upset price being fixed at 12s. per acre, and part

of tho proceeds used in connection with immigration, to this, the

then latest scene of British enterprise. Tho minimum value was

subsequently i-aised to £1 per acre, the same as that which obtained

in the older colony.

Victoria was seimratod from New South Wales in 1851, The

Si-st sale, however, ot town lands in Melbourne, took place so far back

as 1837. Allotments, which now foi'm some of tho most valuable building

sites in the great city of the south, found purchasers then at about

£70 per aero,

Queensland, tho youngest of the Australian colonies, received her

autonomy in 1859. The pioneers of the north, as in fact almost all

over Austialia, were tho squatters. This part of the east coast

aftenvards became known in connection with the Fitzroy Gold

Diggings, and the subsequent settlement of the Eockhampton district.

The Imperial enactment of the year 1842, provided fur the sale of

waste lands in the Australian colonies, which included also Tasmania

(then known as Van Diemen's Land), and New Zealand, This statute

provided that conveyance should not take place unless by the ordinary

method of sale, or private contract, and free grants became a matter

of the past. The minimum upset price was ti.^ed at £l per acre.

Lands of a sjjecial value, on account of their position or character,

were offered at much higher amounts at tho auction sales, appointed

to take place eveiy three mouths.

In August, I8 K5, an Amending Act passed the Imperial Legislature,

which also included within its scope the regulation of the

Pastoral Leases. Tho term of lease for the various runs was fixed at

a maxinianj of 14 years, aud tho rent at £1 per section ot 040 acres.

This statute was tho anthority for the subsequent " Orders in Council."

It provided for a sale of leases remaining in the hands of the Crown

at the end of each year. In 1847, the law was again amended by tho

Imperial Parliament. This Act pwvided for ii special division of

New Soutli Wales, which then included the \vhole of tho eastern aud

south-eastern coasts of Australia. The divisions, which wore based

on the progress of settlouent, wove styled—tin- Pir.^t Class Settled,

tho Second Class Settled, and tlio Unsettled Districts, During 1853,

farther provision was nuide in tho Home Legisliituro for tho ronewal

of pastoral leases iu the Uusettled Districts. At this stage in Australian

history tho whole of the relations of the colonies with regard to tho

¡larent country came before the House of Commons, [n 1842, ¡m Act

had received the Royal assent, which conferred on the senior colony

a mixed Legislative Council. This body, ho^vever, possessed no control

over the lauds, or rents received from the lessees, ririevancos, which

the colonists, removed eo far from the scat of tiovernmont, now

suffered imder, caused some agital iou, and the result ivas t.hat a now

Constitution was granted, which carried iu its tmin local government,

with full powiu' to detennino upon all matters not ot an international

character. From this point a new era cuinmcncod in the history ot

tho colonies, and, as it invigorated with new life, tlioy have since

advanced, and kept apace with the civiliziitiim of the foremost

countries of the Old World.

AUSTRALIA.

The powor of self-government, which was received by the colonists,

contained absolute authority to deal with the public lands as they

thought fit, and entirely for their own benefit. It is easy now to

see the beneficial effect of such a, measure on the small oommunitios,

situated at so great a distance from the controlling power. A very

conservative policy—one almost of complete stagnation—had long

obtained in regard to the occupation of tho waste lands. The auction

sales had not r ; tliis s in a large ir

the faulty and inefBcient character of tlio administration. Delays of

vexatious nature faced the applicant for land at every point. An

unnecessarily long time was occupied in settling the. prelhninaries ot

application, survey, and auction an-angements; and it not unfrequontly

happened that the poor intending settler, who, after exploring new

country, had succeeded in getting a particular blook ctFered, was

piu-jiosoly outbid by some richcr holder of laud in the neighbourhood,

and ho himself compolled to go elsewhere. The feeling among the

colonists culminatod at last in one of general discontent, for it was

seen that influence was the only means of success. At last, in the

year 1861, in New South Wales, tho famous Bill of Sir John (then

Mr,) Kobertson passed the Colonial Legislature, and became law. By

its pi'ovisions, the land, which had hitherto been locked up, except to

those who held rims, was thrown open from the sea-coast to the South

Australian border.

From one extreme the popular feehng was suddenly changed

to one of an opposite character. That which was closed in 18(51

was opened indiscriminately in 1862. Previously, the long delays

caused by survey. See,, had to be endured; now, immediately upon

tho payment of 5s. per acre deposit, possession could be obtained,

and the land placed under cultivation. It is not üie place here to

discuss the wisdom of such au enactment. The other colonies

have also passed laws, from time to time, in connection with their

public lands. There are many points of similarity. All have

attempted, with varying success, to hold out inducements to settlement

on the soil. The several laws now in force throughout

Australia mil bo found treated separately in coimection -with the

geogi-aphy of each colony.

POPULATION,—Since 1788, when the first colony was founded on

the east coast of Australia, up to the present date, tho progress of

these dependencies of the British Crown has boon ever onward, and

now the term Australia ia known among nations in connection with

success, enterprise, and the steady advance of part of the Old World

civilization over a land pi'eviously inhabited by the savage and th©

beasts of the forest. Within the first century of the history of

Australia, we find on the eastern, southern, and western coa-its, and

for considerable distances into tho interior, the homes of prosperous

settlers dotted over the face of tho land, and, in the midst ot the

primeval forest, are seen the meadow-lands, flocks, herds, and fields

if green waving corn, where, but a few years previously, existed tho

brush and jungle-growth of the

gold-fields

ind othei

irithii .few

petals, hav,

lonsiderabU

Australian bush,

its vast snrfaco, and on areas c

ich

ally less stabh

character than those connected mt h agricultural settlement, but yet

forming a part of the whole. Scattered over tho plains, which extend

inland, the homes toads ot tho pastoralists are met with, and at distant

intervals, the towns and villages, \»hich form ml/repSl.s for their

produce, the latter generally occuring at the junctions of roads or

In some parts of Australia, notably tho south and east coasts,

e been t

settlement, and with it the increase in population, h

more rapid than in other portions. Climate and natur

among the facts which have produced this result.

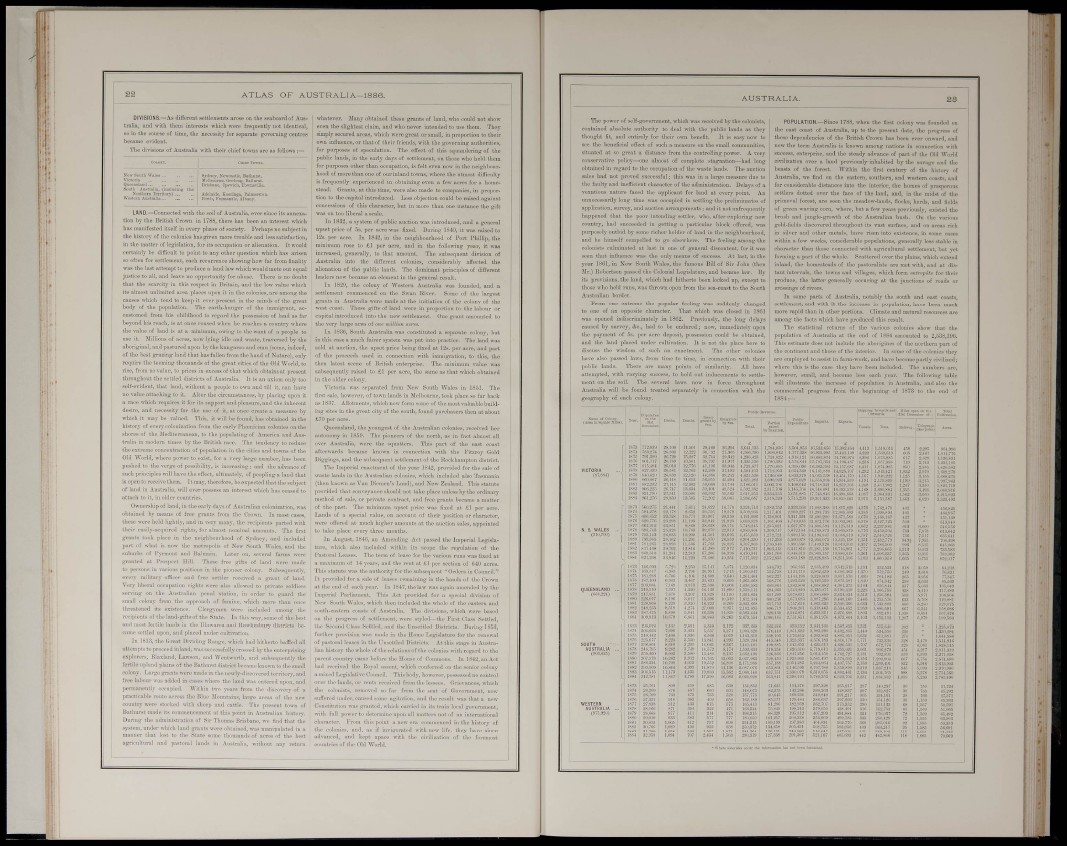

The statistical returns of the vai-ious colonies show that the

popnlotion of Australia at the end of 1884 amounted to 2,538,196.

This estimate does not include the aborigines of tho noi'theni part of

the continent and those of the interior. In some of tho colonies they

are employed to assist in farm-work, and have become partly ci\Hli5ied;

•where this is the case they have been included. The numbers aro,

however, small, and become less each year. The following table

will illustrate the increase of population in .-Vusti-alia, and also the

commereial progress from the beginning ot 1873 to the end of

1884 :—