V' •

! í 1

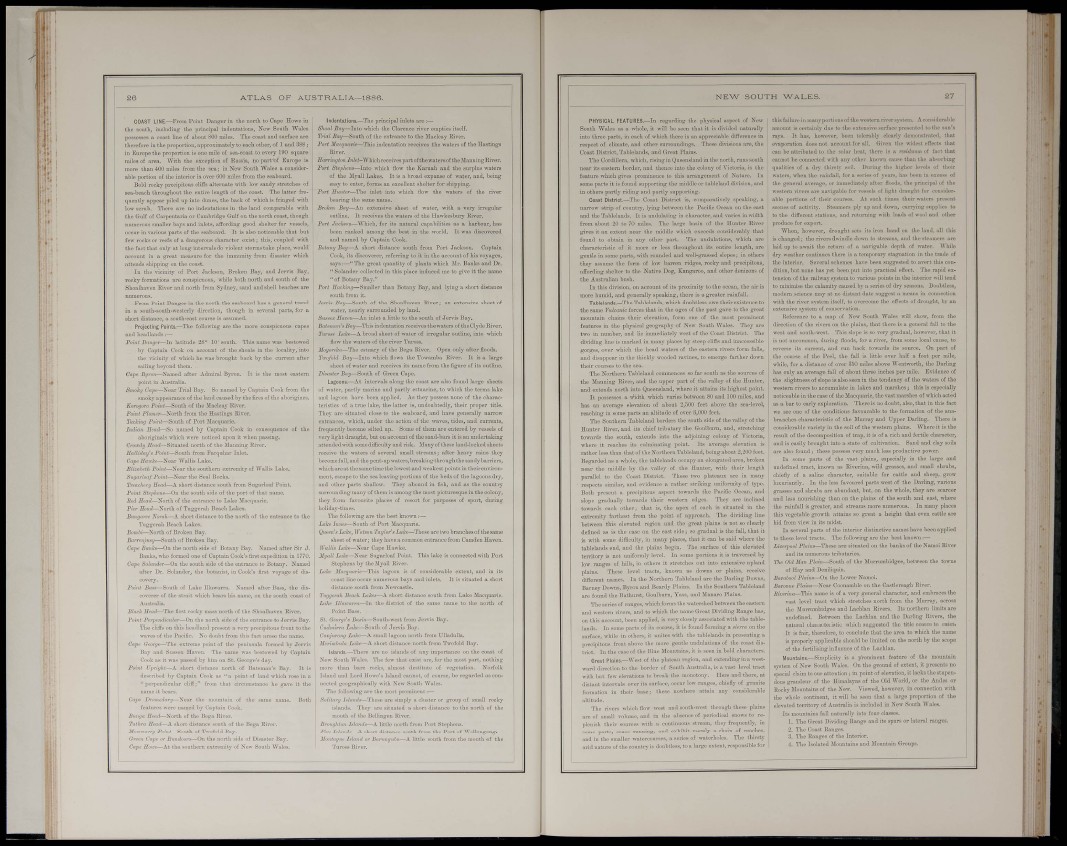

A T L A S OF AUSTRALIA—1886.

COAST LINE—rroiii Point Danger iu the uortli to Cape Howe in

tlio south, inoludiug the principal indentfttious. New South Wales

possesses a coast liuo of about 800 miles. The coast and surface are

therefore iu the proportiou, approximately to each other, of 1 and 888;

in Europe the proportion is ono mile of sea-const to every 190 square

miles of area. With the escuption of Russia, no parfof Europe is

moro than 400 miles from the sea; iu New South Wales a considerable

portion of the Ulterior is over 600 miles from the seaboard.

Hold rocky precipitoas cliffs alternate with low sandy stretches of

sea-beach throughout the entire length of the coast. The latter freqaeiitly

appear piled up into dimes, the back of which is fringed with

low scrub. There are no indentations iu the land comparable with

the Gulf of Cai-pentaritt or Cambridge Gulf on the north coast, though

numerous smaller bays and inlets, affordiug good shelter for vessels,

occur in varioua parts of the seaboard. It is also noticeable that but

few rocks or reefs of a dangerous character exist ¡ this, coupled with

the fact that only at long intervals do riolent storms take place, would

acconnt in a gi-eat measure for the immunity fi-oiu disaster which

attends shipping on the coast,

In the vicinity of Port -Jackson, Broken Bay, and Jervis Bay,

rocky formations are conspicuous, while both north and south of the

Shoalhaven River aud north from Sydney, sand and shell beaches are

From Point Danger iu the north the seaboard has a general trend

iu a south-south-westerly direction, though in several parts, for a

short distance, a south-east coni-se is assumed.

Projeotlng Points.—The foUowing are the more conspicuous capes

and headlands :—

FoiiU Danger—In kiititde 28° 10 'south. This name was bestowed

by Captain Cook on account of the shoals in the locality, into

the vicinity of which he was brought back by the current after

sailing beyond them.

Cape Bijron—Named after Admiral Byron. It is the most eastern

point in Australia.

Smohj Gape—^Near Trial Bay. So named by Captain Cook from the

sinoky appearance of the lanil caused by the fires of the aborigines,

Knrogoru Pt>Í7i¿—South of the Maelesy Hiver.

Poini Plomcr—Sovth from the Hastings Eiver.

Tachiiig Poini—South of Port Maequarie.

Indian Sfad—So named by Captain Cook in consequence of thii

aboi-iginals which were noticed upon it when passing.

Croicdy ifeittZ—Situated north of tlie Manning Rirei-.

Hallidaij's Point—South from Farquhar Inlet.

Near Wallis Lake.

Elizabeth PoÍTii—Near the southern extremity of Wallis Lake.

S«9arZoa/PH¿ni—Near the Seal Rocks.

Treachcry Send—A short distance south from Sngarloaf Point.

Point Stephen»—Oa. the south side of the port of that name.

Red iTeai?—North of the entrance to Lake Maequarie.

Pier Eeiid—North of Tuggerah Beach Lakes.

Buwjane Norah—^A short distance to the north of the entrance to the

Tuggerah Beach Lakes.

£om6i—North of Broken Bay.

Barrenpiey—South of Broken Bay.

Capn Banks—On the north side of Botany Bay. Named after Sir J.

Banks, who formed ono of Captain Cook's fiiat expedition in 1770.

Cape Solander—On the south side of the entmnce to Botany. Named

after Dr. Solander, the botanist, in Cook's first voyage of dis-

Foint South of Lake Illawarra. Named after Bass, the discoverer

of the strait which bears his name, on the south coast of

Australia.

BM Sead—'Ihe first rocky mass north of the Shoalhaven River.

Point Pei'pejuliculaT—On the north side of the entrance to Jei-vis Bay.

The cliffs on this headland present a very precipitous front to the

waves of the Pacific. No doubt from this fact arose the namo.

Cape George—The extreme point of the peninsula formed by Jervis

Bay and Sussex Haven. The name was bestowed by Captain

Cook as it was passed by him on St. George's day.

north of Bat

Í " a point of laud which rose in r

that circumstance he gave it thi

ntaiu of the same name. Boti

Point Upright—A. short di

described by Captain Cook

"perpendicular cliff;" frot

name it bears.

Cape Droinedary—Near the mi

features woi-e named by Captain Cook.

Bwifftt Emd—North of the Bega River.

Talhra Fend—A short distance south of the Bega River.

Moicwarry Puwi—South of ISvofold Bay.

Green Cape or Btindooro—On the north side of Disaster Bay.

Cape ZToife—At the southern extremity of New South Wales.

Indentations.—The principal inlets are:—

Shoal Bay—Into which the Clarence river empties itself.

Trial South of the entrance to the Macleay River.

Port Maequarie—This indeutation receives the waters of the Hastings

Eiver.

fl'arrini/io«./«iui-WhichreoeivespartofthewatersoftheManningBiver.

Port Stepheii»—into which flow the Kai'unh and the surplus waters

of the Myall Lakes, It is a broad expanse of water, and, being

easy to enter, forms an excellent shelter for shipping.

Port B"«n.i£v—'L'he inlet into which flow the waters of the river

bearing the same name.

Brohen Buy—An esteusi'

outlin I t r . •s the

3t of water, mth a very irregular

ers of the Hawkesbury River,

itural capabilities as a barboui-, has

•orld. It was discovered

n Botany Bay, and lying a short distance

1 extensive

Porl /ucton—Which, for its i

been ranked among ilie best i

aud named by Captain Cook.

Botany Bay—A short distance south from Port Jackson. Captain

Cook, its discoverer, referring to it in the account of his voyages,

says:—" The great quantity of plants which Mr. Banks and Dr.

" Solander collected in this place induced me to give it the name

" of Botany Bay."

Port ffncfciup—Smaller

south from it.

Jervis Say—South, of the Shoalhaven

water, nearly smTounded by land.

SIWW.V Eai-on—An inlet a little to the south of Jervis Bay.

Bate,naii's Bni/—This indentation receives the waters of the Clyde River.

Tiiroes Luke—A broad sheet of water of irregular outline, into which

flow the waters o£ the river Tnross.

Mogorehu—The estuary of the Boga River, Open only after floods.

Tviofold Bay—lain which flows the Towamba River. It is a large

sheet of water and receives its name from the figure of its outline.

Disaster Bay—South of Green Cape.

Lagoons,—At intervals along the coast are also found )ai-ge sheets

of water, partly marine and partly estuarine, to which the terms lake

and lagoon have been applied. As they possess none of tie characteristics

of a true lake, the latter is, undoubtedly, their proper title.

They are situated close to the seaboard, and have generally narrow

entrances, which, under the action of the waves, tides, and currents,

ft-eqiiently become silted up. Some of ihem are entered by vessels of

very light draught, but on account of the sand-bars it is an undertaking

attended with some difBculty and risk. Many of these land-locked sheets

receive the waters of several small streams; after heavy i-ains they

become full, and the pent-up waters, breaking through the sandy bamers,

whicharoat the same time the lowest and weakest points in their environment,

escape to the sea leaving portions of the beds of the lagoons dry,

and other pans shallow. They abound in fish, aud as the country

surrounding many of them is among the most picturesque in the colony,

they foim favourite places of resort for purposes of sport, during

holiday-times.

The following are the best known:—

Lake I?tne«—South of Port Maequarie.

Queen's Lake, WateonTayMaLahe—These are two bi-aiiches of the same

sheet of water; tbey have a common entrance from Camden Haven.

Wallis Lake—Ne&v Cape Bawke.

Myall Near Sngarioaf Poin

Stephens by the Myall River.

Lake Maequarie—This lagoon is o

coast line occur numerous bays aud i

distance south from Newcastle.

Tuggerah Beach L<ileea—A short distance

Lake Ilhwarra—In the district of the i

Point Bass.

St. George's Basin—South-west from Jervis Bay.

Cudmirra irJt«—South of Jervis Bay.

Cunjurong Lake—A small lagoon north fi-om Ulladulla.

Merimhula Lake—A short distance north from Twofold Bay.

Islands.—There are no islands of any importance on the coast of

New South Wales, The few that exist are, for the most part, nothing

more than bare rocks, almost destitute of vegetation. Norfolk

Island and Lord Howe's Island cannot, of course, be regarded as connected

geographically with New South Wales.

The foUomng are the most promiuent:—

Solitary Mauds—These are simply a cluster or group of small rooky

islands. They are situated a short distance to the north of the

mouth of the Bellingen River.

Bronghton Islund«—A little north fi-om Port Stephens.

Five lelnndD—A short distance south from the Port of AVollongong.

Monlayue Muud or Barm,gnla—k little south from the mouth of the

Tuross River.

This lake

Dsiderable extent, and in its

inlets. It is situated a short

nth from Lake Maequarie,

lue name to the north of

N E W SOUTH WALES,

PHYSICAL FEATURES.—In regarding the physical aspect of New

SoutJi Wales as a whole, it will be seen that it is divided naturally

into thi-ee parts, in each of which thei'e is an appreciable difference in

respect of olimute, and other surroundings. These divisions are, the

Coast District, Tablelands, and Great Plains.

The Cordillera, which, rising in Queensland in the north, ruus south

near its eastern border, and thence into the colony of Victoria, is the

feature which gives prominence to this arrangement of Nature. In

some parts it is found supjiorting the middle or tableland division, and

in others partly riding and partly supporting.

Coa8t DiBlPiot.—The Coast District is, comparatively speaking, a

narrow strip of country, lying between the Pacific Ocean on the east

and the Tablelands. It is undulating in character, and varies in width

from about 20 to 70 miles, Tho large basin of the Hunter River

gives it an extent near the middle which exceeds considerably that

found to obtain m any other part. Tbe undulations, which are

characteristic of it more or less throughout its entire length, are

gentle in some parts, with rounded and well-grassed slopes; in othera

they assvime the form of low barren ridges, rooky and precipitous,

affording shelter to the Native Dog, Kangaroo, and other denizens of

the Australian bush.

In this division, on account of its proximity to the ocean, the air is

more humid, aud generally speaking, there is a greater rainfaD.

Tablelands.—The Tablelands, which doubtless owe their existence to

the same Vulcanic forces that in the ages of the past gave to the gi'eat

mountain chains their elevation, form one of the most prominent

features in the physical geography of New South Wales, They are

two iu numbei-, and lie immediately west of the Coast District. The

dividing lino is marked in many places by steep cliffs and inaccessible

gorges, over which the head watei-s of the eastern rivers form falls,

and disappear in the thickly wooded ravines, to emerge farther domi

their courses to the sea.

The Northern Tableland commences so far south as the sources of

the Manning River, and the upper part of the valley of the Hunter,

and extends north into Queensland, where it attains its highest point.

I t possesses a width which varies between 80 and 100 miles, and

has an average elevation of about 2,500 feet above the sea-level,

reaching in some parts an altitude of over 3,000 feet.

The Southern Tableland borders the south side of the valley of the

Hunter Rivei-, aud its chief tributaiy the Goulburn, and, stretching

towards the south, extends into the adjoining colony of Victoria,

where it reaches its culminating point. Its average elevation is

i-ather less than that of the Northern Tableland, being about 2,200 feet.

Regarded as a whole, the tablelands occupy an elongated area, broken

near the middle by tho valley of the Hunter, with their length

parallel to the Coast District. These two plateaux are in many

• respects similar, and endence a rather striking uniformity of typo.

Both present a precipitous aspect towards the Pacific Ocean, and

slope gradually towards their western edges. They are inclined

towards each other; that is, the apex of each is situated in the

extremity farthest from the point of approach. The dividing line

between this elevated region and the great plains U not so clearly

defined as is the case on the east side; so gradual is tho fall, that it

is with some difficulty, iu many places, that it can be said where the

tablelands end, and tho plains begin. The surface of this elevated

territory is not unifoimly level. Iu some portions it is ti-aversed by

low i-anges of hills, in othere it stretches out into extensive upland

plains. These level tract-s, known as downs or plains, receive

different names. In the Northern Tableland are the Darling Downs,

Barney Do^vns, Byrou and Beardy Plains, In the Southern Tableland

are found the Bathnrst, Goulburn, Tass, and Manaro Plains.

T'he series of ranges, which fonns the watershed between the eastern

and western rivers, and to which the name Great Dividing Range has,

on this account, been applied, is very closely associated with the tablelands.

In some parts of its course, it is found forming a sierra on the

surface, while in others, it unites with the tablelands in presenting a

precipitous front above the more gentle undulations of the coast district.

In the case of the Blue Mountains, it is seen iu bold characters.

Great Plains.—West of the plateau region, and extending in a westward

direction to tho border of South Australia, is a vast level tract

with but tew elevatious t-o break the monotony. Here and thore, at

distant intervals over its surface, occur low ranges, chiefly of granite

I their base; thes >where attain usiderablc

plenish their

some parts,

and in the sit

west and south-west through those plains

iu the absence of periodical snows to reb

a continuous stream, they frequently, in

g, aud exhibit merely a chain of reaches,

ourses, a series of waterlioles. The thirsty

is doubtless, to a large extent, responsible for

this failure iu many portions of the western liver system. Aconsidorable

amount is certainly due to the extanaivo surface presented to the sun's

rays. It has, however, been tolerably clearly demonstnited, tliat

evapoi-ation does not account for all. Given the widest effects that

can be attributed to the solar heat, there i» a resitlmim of fact that

cannot be connected with any other known cause than tbe absorbing

qualities of a dry thirsty soil. Dnriug the highei' levels of their

waters, when the rainfall, tor a series of years, lias been in excess of

tho general average, or immediately after floods, the jiriricipiil of the

western rivers ai'e navigable tor vessels of light draught for considerable

portions of their courses. At such times their waters present

scones of activity. Steamers ply up and do^-n, carrying supjilies to

to the different stations, and returning with loads of wool aud other

produce for export.

When, ho\»evor, drought sots its iron hand on the land, all this

is changed; the rivers dwindle down to streiims, and the steumere are

laid up to await the return of a navigable depth of water. While

dry weather continues there is a tempurary stapiation in the trade of

the interior. Several schemes have been suggested to avert this condition,

but nono has yet been put into practical effect. 'J'he rapid extension

of the railway system to various points in tho interior will tend

to minimise the calamity caused by a series of dry seasons. Doubtless,

modem science may at no distant dat

;e suggest a means iu connectio

with the river system itself

ime the effects of drought, by a

extensive system of consei-vation.

Reference to a map of New South Wales will show, from the

direction of tlie rivers on the plains, that thore is a general fall to the

west and south-west. This slope is so very gradual, liowever, that it

is not uncommon, during floods, for a river, from some local cause, to

reverse it« current, and run back towards its source. On part of

the coui-se of the Peel, the fall is little over half a foot per mile,

while, for a distance of over 850 miles above Wentworth, the Darling

has only an average fall of about three inches per mile. Evidence of

the slightness of slope Is also seen in the tendency of the waters of tho

western rivei-s to accumulate in lakes and marshes; this is especially

noticeable in the case of tho Maequarie, the vast marshes of which acted

as a bar to early exploration. There is no doubt, also, that in this fact

we see ono of the conditions favourable to the formation of the anabranches

characteristic of the Murray aud Upper Darling. There is

considerable variety in the soil of the western plains. Where it is the

result of the decomposition of trap, it is of a rich and fertile character,

and is easily brought into a state of cultivation. Sand and clay soils

are also found; these possess veiy much less productive power.

In some parts of the vast plains, especially in the large and

undefined tract, known as Riverina, wild grasses, and small shrubs,

chiefly of a saline character, suitable for cattle and sheep, grow

luxuriantly. In the less tavoared pai-ts west of the Darling, various

grasses and shrubs are abundant, but, on the whole, they are scarcer

and less nourishing than on the plains of the south and east, where

the rainfall is greater, and streams more numerous. In many places

this vegetable gi'owth attains so great a height that even cattle are

hid from view iu its midst.

In several parts of the interior distinctive names have been applied

to these level ti-aats. The following are the best known:—

Liverpool Pinuii—These are situated on the banks of the Namoi River

tributaries.

The Old Man Plain—South of the Murrumbidgee, between tbe towns

of Hay aud Deniliquin.

Barabool Plains—On the Lower Namoi.

Baromte Plains—I^Se&r Coonamble on the Castlereagh River.

Rivonna—This name is of a very general character, aud embraces the

vast level tract which stretches north from the Murray, across

the Murrumbidgee and LacHan Rivera. Its northern limits are

undefined. Between the Lachlan and the Dai-ling Rivers, the

natural characteristic which suggested tho title ceases to exist.

It is fair, therefore, to conclude that the area to which the name

is properly applicable should bo limited on the north by the scope

of the fertilising influence of tbe Lachlan.

Mountains.—Simplicity is a prominent feature of the mountain

system of New South \Valos. On the ground of extent, it present-s no

special claim to our attention ; iu point of elevation, it lacks the stupendous

grandeur of the Himalayas of the Old World, or tbe Andes or

Bocl-y Mountains of the New. Viewed, however, in connection with

the whole continent, it will be seen that a large proportion of the

elevated territory of Australia, is included in New South Wales.

Its mountains fail naturally into four classes.

1. The Great Dividing Range and ita spurs or lateral ranges.

2. The Coast Ranges.

8. The Ranges of the Interior.

4-. The Isolated Mountains and Mountain Groups.