THE CAUSES OF TLUCTUATIONS IN TrKGESCEyCE

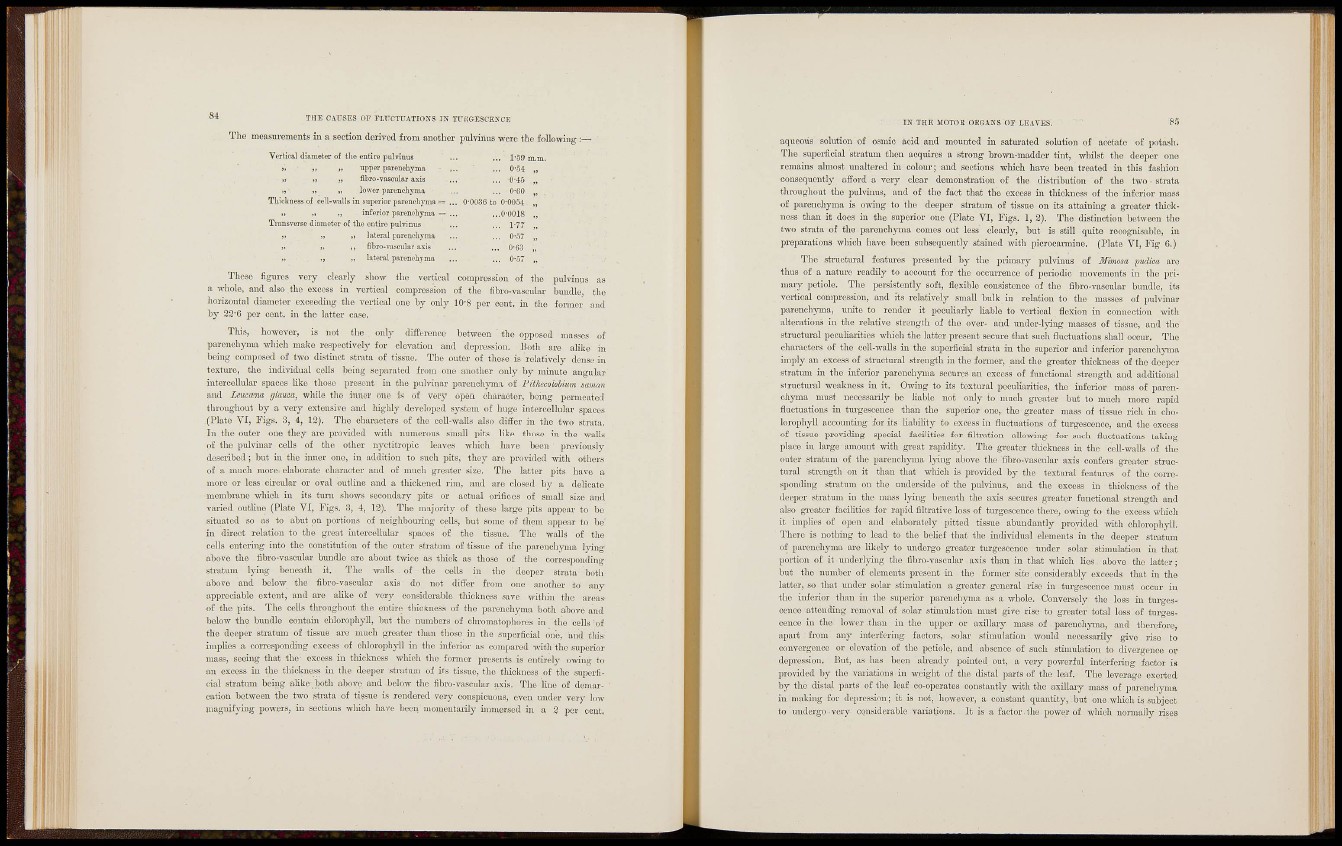

Tho measurements in a section derived from another puHnus were the following :—

Vertical diameter of tlie entire pulvinus ... 1-59 m.

„ „ upper parenchyma ... 0-5.\ ,,

„ „ fibro-vftsoulfu-axis ... 0'45 „

1, „ lower pnieuohyma ... 0-60

TUioknes s of oell-walls in superior paiencliynia = .. . 0-0036 to 0-0054 „

„ „ inferior parenchyma = .. ...0-0018 ,.

Transver se diameter of the entbe pulvinus ,.. 1-77 ,.

,, ,1 lateral parenchyma ... 0-57 ,,

„ ,, fibro-vascular axis ... o-es „

,, ,1 lateral parenchyma ... 0-Û7 ,,

tlie vertical compression of the piilvinus as

compression of the tibro-vasunlar bundle^ the

These figures veiy clearly show

a whole, and also the excess in Tertical

liorizontal diameter exceeding the Tertical one by only 10-8 per cent, in the former njid

by 22-6 per cent, in the latter case.

This, however, is not the only differenco between the opposed masses of

parenchyma which make respectively for elevation and de])ression. Both are alike iii

being composed of two distinct strata of tissue. Tho outer of these is relatively dense in

texture, tlie individual cells being separated from one another only by minute angular

intercellular spaces Hke those present in the pulvinar parenchyma of FHhecolohmm saman

and Leuccem giauaa, while the inner one is of very open character, being permeated

throughout by a very extensive and highly developed system of huge ititercellular spaces

(Plate Vi, Figs. 8, 4, 13). The characters of the cell-walls also differ in the two strata.

In the outer one they are provided with numerous small pits like those in the walls

of the pulvinar cells of the other nyctitropic leaves which have been previously

described; but in the inner one, in addition to such pits, they are provided with otiiers

of a much more elaborate character and of much greater size. Tlio latter pits have a

more or less cii-cular or oval outline and a thickened rim, and are closed by a delicate

membrane which in its turn shows secondary pits or actual orifices of small size and

varied outhnc (Plate VI, Figs. 3, -4, 12). The majority of these large pits appear to be

situated so as to abut on portions of neighbouring cells, but some of them appear to be'

in direct relation to the great intercellular spaces of the tissue. The walls of the

cells entermg into the constitution of tho outer stratum of tissue of the parenchyma lyingabove

the fibro-vascular bundle are about twice as thick as those of the corresponding

stratum lying beneath it. The walls of the cells in the deeper strata both

above and below the fibro-vascular axis do not differ from one another to any

appreciable extent, and are alike of very considerable thickness save within tho areas

of the pits. The cells throughout the entire thiclcness of the parenchyma both above and

below the bundle contain chlorophyll, but the numbers of chromatophores in the cells of

the deeper stratum of tissue are much greater than those in the superficial one, and this

impHes a coiTesponding excess of chlorophyll in the inferior as compared witli the sui)erioi'

mass, seeing that the cxcess in thickness which the former presents is entirely owing to

an excess in tho thickness in the deeper stratum of its tissue, tho tliickness of the su]>eriic.

ial stratum being alike .both above and below the fibro-vascular axis. The line of demar- '

cation between the two strata of tissue is rendered very conspicuous, even under very low

inagnifying powers, in sections wliich have been momentarily immersed in a 2 per cent.

IN THE MOTOE OKGA^iS OF LEAVES.

aqueous solution of osmic acid and mounted in satm-ated solution of acetate of potash.

The superficial sti'atum then acquires a strong brown-madder tint, whilst the deeper one

remains almost unaltered in colour; and sections which have been treated in this fashion

consequently afford a veiy clear demonstration of the distribution of the two • strata

throughout the pulviuus, and of the fact that the excess in thickness of tho inferior mass

of parenchyma is owing to the deeper sti-atum of tissue on its attaining a greater thiclcness

than it does in the superior one (Plate VI, Figs. 1, 3). The distinction between tho

two strata of the parenchyma comes out less clearly, but is still quite recognisable, in

preparations which have been subsequently stained with picroeai-mine. (Plate VI, Fig 6.)

The structm-al features presented by the primary pulvinus of Mimosa piulica are

thus of a nature readily to account for the occuiTence of peiiodic movements in the i)rimaiy

petiole. The persistently soft, flexible consistence of tho fibro-vascular bundle, it.s

vortical compression, and its relatively small bulk in relation to the masses of pulvinar

parenchyma, unite to render it peculiarly hable to vertical flexion in connection with

altcratioirs in the relative strength of the over- and under-lying masses of tissue, and tho

structural peculiaritic-s which the latter present secure that such fluctuations shall occur. The

characters of tiie cell-walls in the superficial sti-ata in the superior and inferior parenchyma

imply an excess of stractural strength in the former, and the greater thickness of the deeper

stratum in the inferior parenchyma secures an excess of functional strength and additional

structural weakness in it. Owing to its textm'al peculiarities, the inferior mass of parenchyma

must necessarily be Hable not only to much greater but to much more rapid

fluctuations in tm-gescence than the superior one, the greater mass of tissue rich in cholorophyll

accounting for its liability to excess in fluctuations of turgescence, and the excess

of tissue providing special facilities for filtration allowing for such fluctuations taking

place in large amoîint with great rapidity. The greater tliickness in the ccll-walls of the

outer stratum of the parenchyma lying above the fibro-vascular axis confers greater structural

strength on it than that which is provided by the textural features of the corresponding

stratum on the underside of the pulvinus, and the excess in tliickness of the

deeper stratum in the mass lying beneath the axis secures greater functional strength and

also greater facilities for rapid filtrative loss of tm-gescence there, owing to the excess which

it implies of open and elaborately pitted tissue abundantly provided with chlorophyll.

There is nothing to lead to tho beKef that the individual elements in the deeper stratum

of parenchyma are likely to undergo greater tm-gescence under solar stimulation in that

portion of it underlying the fibro-vascular- axis than in that which lies above the latter ;

but the number of elements present in the former site considerably exceeds that in tho

latter, so that under solar stimulation a greater general rise in tm-gesccnce must occur in

the inferior than in the superior parenchyma as a whole. Conversely the loss in turges^

cenco attending removal of solar stinml&tion must give rise to greater total loss of turgescence

in the lower than in the upper or axillary mass of pai-enchyma, and therefore,

apart from any interfering factors, solar stimulation would necessarily give rise to

convergence or elevation of the petiole, and absence of such stimulation to di\'orgence or

depression. But, as has been ah-cady pointed out, a very powerful interfering factor is

provided by tho variations ii\ weight of the distal parts of the leaf. The leverage exerted

by the distal paits of tho leaf co-operates constantly with tho axillary mass of parenchyma

in making for depression; it is not, however, a constant quantity, but one which is .subject

to undergo very considerable variations. It is a factor , (he power of wliich noi-mally rises