38 THE CAUSES OP FLFCTUATIOÎîS IM TUfiGESCENCE

above tlie great basal cell is apparently quite empty of all save fluid, At the same

tiiiie it is clearly related to continued protoplasmic activity, aitiioiigli tliis is not carried

on locally. This is shown very strikingly in cases where the mycelium and basal cells

are subjected to the influence of osmic acid. If a mass of tlie cowdnng on which a

crop of fertile filaments in full turgescence is situated bo moistened by a 2 per cent,

solution of osmic acid, and set under a dissecting microscope, a very beautiful and

interesting series of phenomena manifest themselves witliin the course of a minute or

two. Under normal cii-cumstances, of coxn-se, the turgescence in the fertile filaments is

so excessive as to give rise to such a considerable excretion of fluid that they are

studded tlu'oughout by beads of it. Under the inflxience of the osmic acid these beads may

be seen rapidly to enlarge, and as they do so the filament gradually becomes flaccid and

collapses. The very fact that this rapid and complete collapse should attend the action

o£ osmic acid is in itself very strong evidence that the turgescence is independent of the

presence of any continuous stratum of protoplasm, seeing that the fixative property of

this re-agent for tissue elements seems to bo due to its action in rendering the protoplasm

relatively hnpermeable ; and, when taken along -with the histological evidence, it seems

conclusively to indicate that we are here dealing with turgescence due to extrinsic

agencies, due to the presence of materials which have not originated locally, but which,

having been developed in connection with the functional activity of the mycelium and

specially of the basal cells, have passed on into the interior of the fertile filaments.

Further, it is evident that these materials must be of unstable nature, so that turgescence

can only maintain itself against the factors making for fllti-ation so long as a constant

supply of them is being manufactured elsewhere and subsequently transferred to the

cavities of the filaments.

Perhaps the most convincing proof of the indirect relation which turgescence bears

to protoplasmic functional propei-ties, and of its dii-ect dependence on osmotic peculiarities

in the cell-sap, is that which is afforded b y the results of experiments in which, in the

course of killing the protoplasts of the tissues, we secure the artificial addition of osmotic

constituents to the sap. When we do so, we find in dealing with succulent tissues, such

as those of Kahnchoe, in wliich an abolition of protoplasmic activity is normally accompanied

by a very large discharge of fluid and loss in weight and turgescence, that death

is not accompanied by any considerable diminution in weight or turgescence, and that the

dead tissues may persist for prolonged periods in a highly turgid condition. The following

experimental details illustrate very clearly the different effects produced on turgidity

of tissue where death is detei-mined with or without the addition of osmotic materials

to the cell-sap :—

Experiment XIX.—Two leaves of Kalanchoe—one, a, weighing 28'22, the other, h,

27-54: gi-ammes—were taken and set with the bases of the petioles immersed in water.

The lower extremities of the petioles were tlien cut off subaqueously, so as to permit of

f r e e absoi-j^tion, and leaf a set in a chloroform-chamber, and I in an ammoniacal one.

Copious sweating set in in a within half an hour, and advanced so rapidly that the lobes

had begun to collapse within an hour from the beginning of the experiment, the tissue

at the same time beginning to acquire a yellowish tinge. In the case of I, a limited

ainomit of exudation appeared very rapidly, and the tissue acquired an intense deep green

tint, but no considerable loss of fluid occurred, and the leaf remained perfectly firm and

showed no signs of collapse. Thi3 ammonia appeared to act more rapidly in causing

IH THE MOTOR ORGANS OF LEAVES. 29

exudation than the chloroform, but the action appeared very soon to be an-ested before

suflicient loss had occurred to induce appreciable loss in tui-gidity; whilst, in the case of

the chlorofonn, when exudation had once been established it advanced rapidly and

steadily. On the following day the leaf a was of a pale yellowish olive colour and

perfectly flaccid and collapsed, whilst J was deep dark-green and quite firm and turgid.

The loss of weight which had occurred in a was 7'75 grammes, or 27-i per cent., and

active exudation was still taking place. In the case of b the loss only amounted to r64,

or 0'9 per cent., and there was no sign of any continued exudation. Subsequently to this

b only was kept under observation, being weighed at intervals and having a fresh pctiolar

surface exposed each time that it was returned to the chamber. Twenty-four hours

subsequently to the previously recorded observation, in place of sho-vving any loss of weight,

it showed a gain of 0'42; and a week after the initiation of the experiment the tissue

remained highly turgid, and the total loss of weight for the entire period only amounted

to 1-64 grammes, or 5'9 per cent. The weights at different periods are shown in the

following table:—

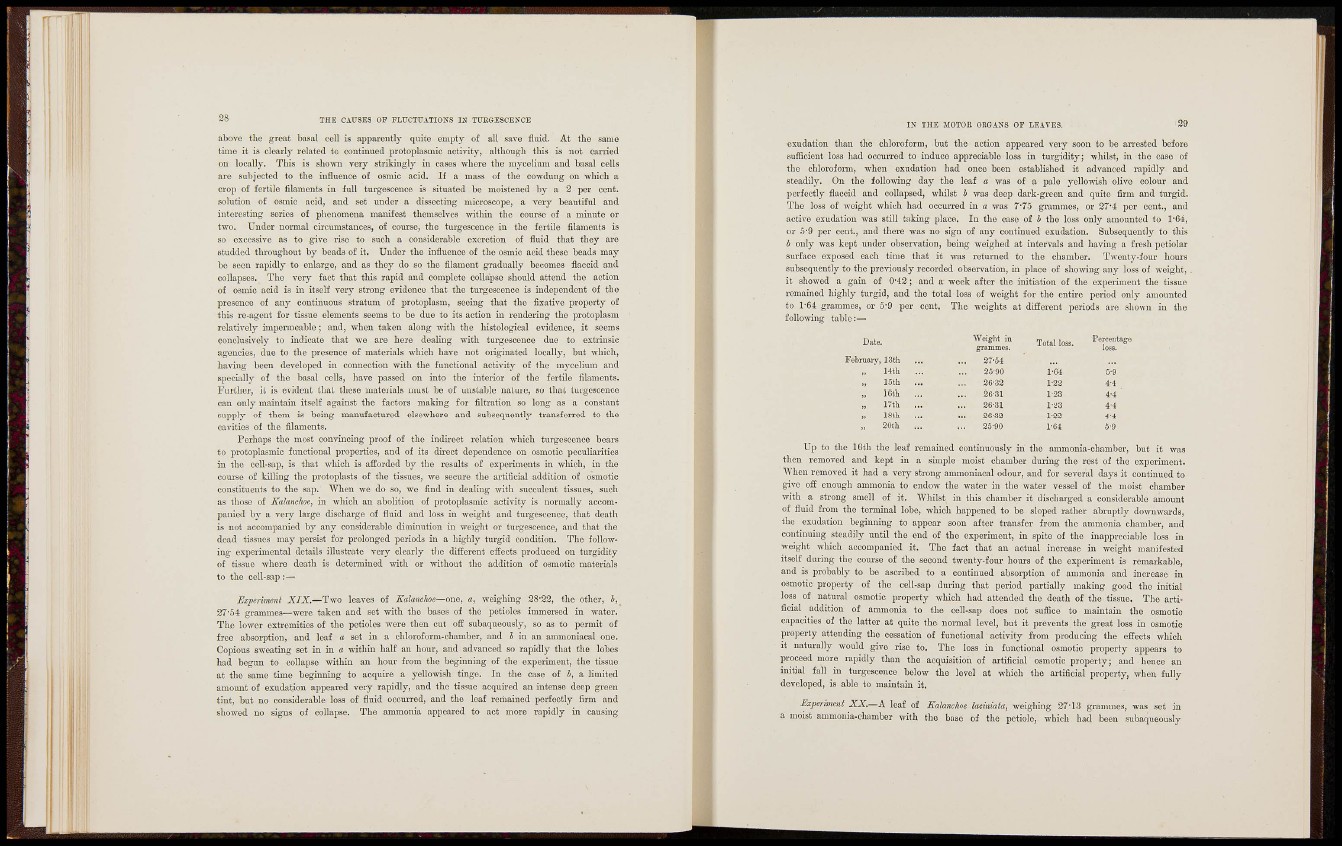

Date. Weight in Total loss. Perceiitago

grammes. loss.

February, 13th ... 27-54

14tli ... 25-90 1-G4 5-9

loth ... 26'32 1-22 4-4

l e t i ... 26'31 1-23 4-4

ITtli ... 26-31 4-4

18tli ... 26-32 1-22 4-4

20th ... 25-90 1-64 5-9

Up to the 16th the leaf remained continuously in the ammonia-chamber, but it was

then removed and kept in a simple moist chamber during the rest of the experiment.

"When removed it had a very strong ammoniacal odour, and for several days it continued to

give off enough ammonia to endow the water in the water vessel of the moist chamber

with a strong smell of it. Whilst in this chamber it discharged a considerable amoimt

of fluid from the terminal lobe, which happened to be sloped rather abruptly downwards,

the exudation beginning to appear soon after transfer from the ammonia chamber, and

continuing steadily until the end of the experiment, in spite of the inappreciable loss in

weight which accompanied it. The fact that an actual increase in weight manifested

itself during tlie course of the second twenty-four hours of the experiment is remarkable,

and is probably to be ascribed to a continued absorption of ammonia and increase in

osmotic property of the cell-sap during that period pai-tially making good the initial

loss of natural osmotic property which had attended the death of the tissue. The artificial

addition of ammonia to the cell-sap does not suffice to maintain the osmotic

capacities of the latter at quite the noi-mal level, but it prevents the great loss in osmotic

property attendmg the cessation of functional activity from producing the effects which

It naturally would give rise to. The loss in functional osmotic property appears to

proceed more rapidly than the acquisition of artificial osmotic property; and hence an

initial fall in turgescence below the level at which the artificial property, when fully

developed, is able to maintain it.

Experiment XX.—A leaf of Ealanclm laciniata, weighing 27-13 grammes, was set in

a moist ammonia-chamber with the base of the petiole, which had been subaqueously