32 TEB CAUSES OF FLUCTUATIONS IN TURCESCENCE

whicli they wore set. One of them, «, was now placed in an ammonia-chamber, and

tho other, b, in a chloroform one. The petals of a immediately began to show purplish

black spotting, which rapidly extended over their entire surface. The colour next

gradually assumed a greenish tint and ultimately became of a fine warm ochre.

Whilst those changes were occurring there were no signs of loss of tm-geseence, and

it was not until some hours after theii- full completion that a little exudation and a

trace of collapse manifested themsolvos. In the case of b the action of the abnormal

medium did not manifest itself for some time; but, when once initiated, alteration in

colour and loss of turgescence ran hand in hand, and after the close of a few hours

the colour was of a dull maroon red and tho tissues of tho flower were completely

flaccid and collapsed. Twenty-four hours after the mitiation of the experimeut, a was

slightly collapsed, but after this it remained apparently unaltered for some days.

Experiment XXII.—Two flowers of scarlet Hibiscus were taken, and one, a,

suspended free, apex downwards, in an ammonia-chamber, whilst the other, b, was

similarly hung in a chloroform-chamber. In the case of a, discolouration, in the form of

black spotting of the petals, made its appearance at once, and within an horn- the red

had entirely gone, save in a few isolated patches, and the rest of the tissue was deep

purpllsh-black, passing into deep greenish and ochre at the margins. There was, however,

no indication of any tendency to collapsc. In b discolouration was developed

much more slowly; but at the close of an hour the original vivid scarlet had

been replaced by a deep maroon, and the petals, which had originally been higlily

reflexed, were drooping downwards and rapidly collapsing. The first traces of collapse

in a did not appear until three hours after the beginning of the experiment, and even

then the petals remained highly reflexed. On the following day the petals of a were

drooped, but still widely divergent and firm in texture (plate I I I . fig. 3); whilst those

in b hung vertically downwards and were perfectly flaccid (plate I I I . fig. 4). Twentyfour

hours later the • petals of a were slightly less divergent than they had been, but

were still so divergent as to allow the stigmas to be visible beyond them in profile.

Both flowers were now removed from the chambers and hung in the open laboratory,

where they remained for days apparently unaltered, b being fully collapsed and a

retaining a considerable amount of turgidity.

Experiment X X / / / . — T w o flowers of scarlet Hibiscus were, as in the previous

case, placed respectively in ammonia and chloroform-chatqbers. They were not, however,

suspended, but were set with the freshly, subaqucously divided extremities of

their stalks immersed in water. As in the previous experiment, the flower in

the ammonia chamber began to show black spotting immediately, and rapidly passed

on through stages of deep purplish black and. deep greenish to a uniform warm ochi-e

without showing any signs of collapse; whilst that in the chlorofonn-chamber took

some time to show any signs of change in colour, but when it once had begun to

discolour, began also to collapse rapidly. On the following morning a slight amount of

collapse only was evident in a, whilst b was completely collapsed, flaccid, and soaked.

The ammonia-chamber was allowed to stand unopened for a week, and during

that period a remained almost in tho same condition as it was in after twenty-four

hours' exposure.

From the results obtained in tlie first of these experiments it is evident that tlie

retention of turgescence in such cases is not wholly due to the presence of free

IN THE MOTOR ORGANS OF LEAVES. 33

ammonia in the tissues, but that combinations must be formed within the cell-sap

which render it more or less permanently hygroscopic. The flower a did not undergo

complete collapse on removal from the ammonia chamber, but remained partially

turgid even after prolonged exposure in the open air. There can, therefore, be no

doubt that turgescence is mainly, if not solely, due to the osmotic properties of the

cell-sap, and that losses in turgescence are due to diminished osmotic capacity in the

latter, and not to any increased filtrative properties in the protoplasm. It is not,

however, quite clear that sü-uctural alterations in the protoplasm may not act in tho

contrary direction, in the way of retarding losses in turgescence by presenting an

abnormal resistance to the elastic recoil of the cell-walls. When we consider tho phenomena

presenting themselves in connection with death of tissues under the influence

of the vapour of osmic acid, there are many points suggesting that the abnormal

slowness with which loss of turgescence advances is due to such a causation. This

is shown by the data furnished by the next two experiments.

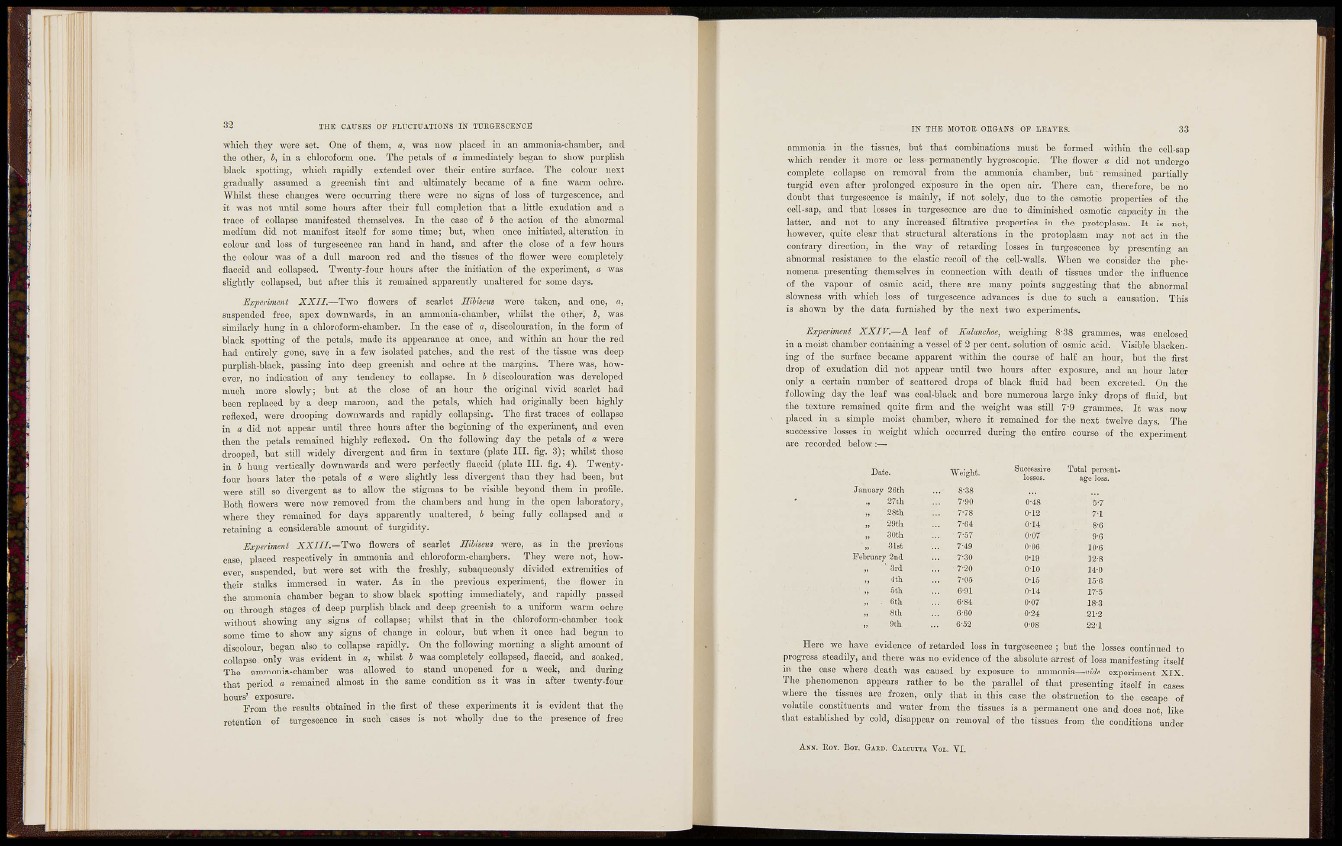

Experiment XXIV.—A leaf of Ealanchoe, weigliing 8-38 grammes, was enclosed

in a moist chamber containing a vessel of 2 per cent, solution of osmic acid. Visible blackening

of the surface became apparent within the course of half an hour, but the first

drop of exudation did not appear until two hours after exposure, and au hour later

only a certain number of scattered drops of black fluid had been excreted. On the

following day the leaf was coal-black and bore numerous large inky drops of fluid, but

the texture remained quite fii-m and the weight was still 7-9 grammes. It was now

placed in a simple moist chamber, where it remained for the next twelve days. The

successive losses in weight which occurred during the entire coiirse of the experiment

are recorded below :—

Date. Weight. Successive Total percentage

loss.

January 26th 8-38

27tb 7-90 0-48 5-7

28th 7-78 0-12 7-1

29th 7-64 0-14 8-6

„ 30tli 757 0'07 9-6

„ 31st 7-49 0'06 10-6

February 2nd 7-30 0-19 12-8

„ • 3rd 7-20 0-10 14-0

4th 7-05 0'15 15-6

5th 6'91 0-14 175

„ . 6th 6'84 0-07 18-3

8th 6-60 0-24 21-2

9lh 6-52 008 22-1

Here we have evidence of retarded loss in turgescence ; but the losses continued to

progress steadily, and there was no evidence of the absolute arrest of loss manifesting itself

m the case where death was caused by exposure to ammonia—vide experiment XIX.

The phenomenon appears rather to be the parallel of that presenting itself in cases

where the tissues are frozen, only that in this case the obstruction to tho escape of

volatile constituents and water from the tissues is a perinanent one and does not like

that established by cold, disappear on removal of the tissues from the conditions under

ANN. EOY. B o r . GAKK, CALCUTTA VOL. V I .