THE CAUSES OF FLUCTUiTIOiig IN TaIlGESCE^^CE

wlueli it orighiatQil. In cases of exposixro to an atmosphere of amuionia there is no

eviilcnco of any initial obstruction to the escape of fluid; on the contrary, exudation manifests

itself with sijecial rapidity, ai\d it is only after some time tliat loss of turgeseecno

ceases to occur and a condition of equilibrium is established between the osmotic capacities

of the tissues and the elastic recoil of tho cell.-walls; but, "when cquilibriuui has been

arrived at, it is stable. In the case of exposure to an atmosphere of osmic fumes, on the

other hand, wo have from the outset very distinct evidence of tho action of a factor

obstructive to tho normal loss in turgcscouce attending death. Exudation appears exceptionally

late and advances very slowly; but, once established, it advances evenly and con-

' tinuously, and there is no tendency to any establishment of a stable equilibrium until thcs

elastic recoil of tho cell-walls has been fully satisfied. We have here evidence showing that

alterations in the protoplasm may retard the progress of the effects following loss in

osmotic property in the cell-sap, but none to shoAv that any mero alterations in the

protoplasm will suffice to givo I'ise to loss in turgescence so long as the osmotic properties

of the cell-sap remain unaltered.

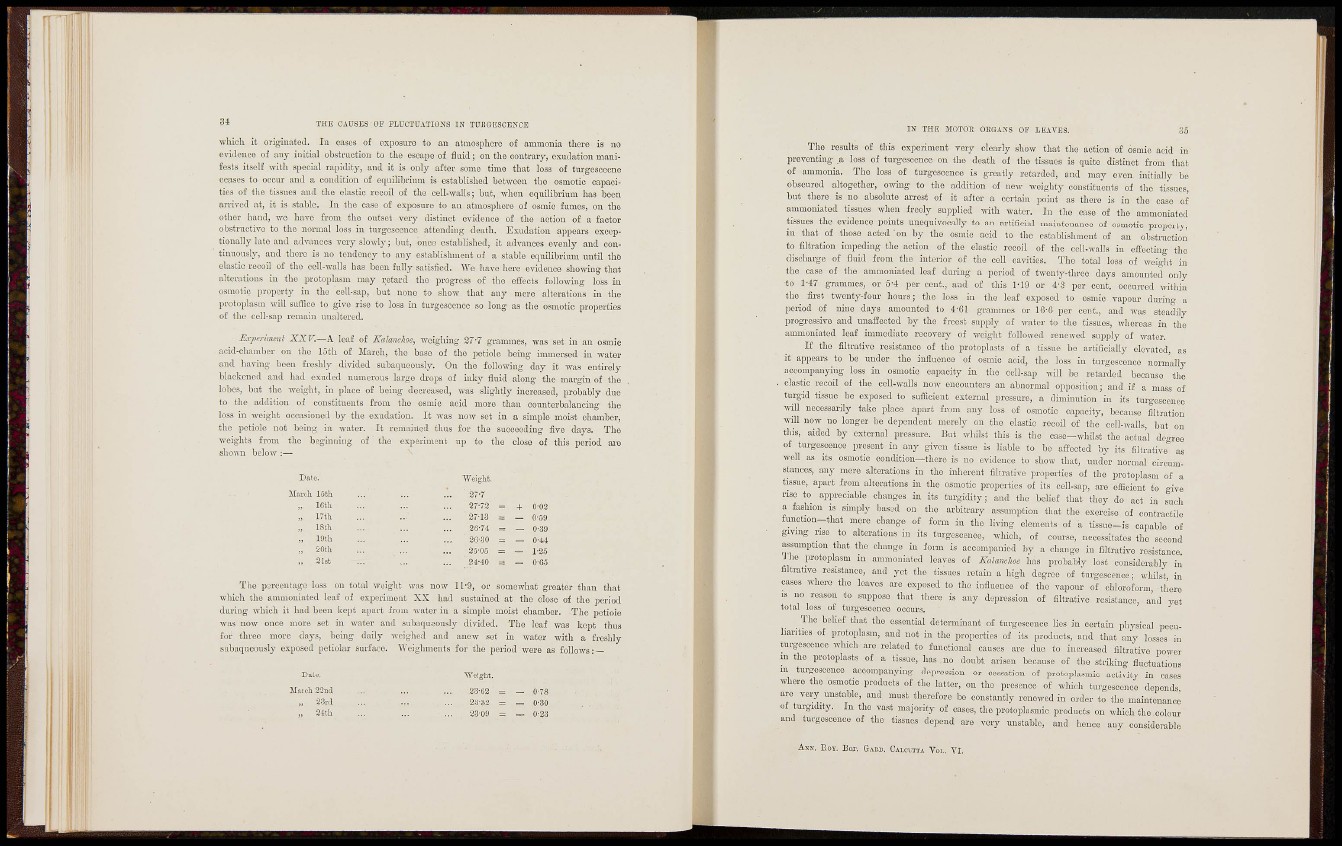

Experiment XXV.—k leaf of KalancJm, weighing 27*7 grammes, was set in an osmic

acid-chamber on tho 15th of March, the base of the petiole being immersed iu water

aud having been freshly divided snbaqncously. On the following day it was entirely

blackened and had exuded numerous large tb-ops of injiy fluid along the margin of the

lobes, but the weight, in place of being decreased, was slightly increased, probably duo

to the addition of constituents from the osmic acid more than counterbalancing the

loss in weight occasioned by the exudation. It was now set in a simple moist chamber,

the petiole not being in water. It remained thus for the succeeding five days. The

weights from tho beginning of tho experiment up to the close of this period are

shown below ;—

Date. •Weight.

March loth 27-7

„ 16tli 27-72 = + 0-02

„ iTtli 27-13 = 0-59

„ ISth 26-74 = 0-39

„ 19th 26-30 = 0-44

„ SOth 25-05 = 1-25

„ 21st 24-40 =i - 0-65

Ttie percentage less on total weight was now 11-9, or somewhat greater than that

which the ammoniated leaf of experiment XX had sustained at the close of the period

during which it had been kept apart from water in a simple moist chamber. The petiole

was now once mora set in water and subaqaeonsly divided. The leaf was kept thus

for three more days, being daily weighed and anew set in water with a freshly

sabaqueously e.^poscd petiolar surface. "Weighmcnts for the period were as follows: —

Date.

Mai oil 22nd

„ 23nl

,, 24tli

Weight.

= _ 0-30

23 09 = — 0-23

IN THE MOTOE OHGAIiS OP m.-iVES. 35

The results of this experiment very clearly show that the action of osmic acid in

preventing a loss of turgescence on the death of the tissues is quite distinct from that

of ammonia. Tho loss of turgescence is greatly retarded, and may even initially bo

obscured altogether, owing to tho addition of new weighty constituents of the tissues,

but there is no absolute arrest of it after a certain point as there is in the case of

ammoniated tissues when freely supplied mth water. In tho case of the ammoniated

tissues tho evidence points unequivocally to an artiBcial maintenance of osmotic property,

in that of those aeted on by tho osmic acid to tho establishment of an obstruction

to filtration impeding the action of tho elastic recoil of the cell-wahs in effecting tho

discharge of fluid from the interior of the cell cavities. The total loss of weight in

the case of the ammoniated leaf daring a period of twenly-threo days amounted only

to 1-47 grammes, or 5-4 per cent., aud of this MO or 4-3 per cent, occurred within

the first twenty-four hours; the loss in the leaf exposed to osmic vapour during a

period of nine days amounted to 4-61 grammes or 16-6 per cent., and was steadily

progressive and unaffected by the freest supply of water to the tissues, whereas in the

ammoniated leaf immediate recovery of weight followed renewed sujiply of water.

If the fihrative resistance of the ¡jrotoplasts of a tissue be artificially elevated, as

it appears to be rmder the influence of osmic acid, the loss in turgescence normally

accompanying loss in osmotic capacity in tho cell-sap will be retarded because the

. clastic recoil of the cell-walls now encounters an abnormal opposition; and if a mass of

turgid tissue be exposed to suffieiout external pressure, a diminution ir its turgescence

wiU necessarily take placc apart from any loss of osmotic capacity, because filtration

wdl now no longer be dependent merely on the elastic rccoil of the coll-walls, but on

this, aided by external pressiu-e. But whilst this is the case—whdst the actual de^ee

of turgcseenoe present in any given tissue is liable to be affccted by its fillralive° as

well as its osmotic condition—there is no evidence to show that, under normal cheumstanccs,

any mere alterations in the irrherent filirativc properties of tho protoplasm of a

tissue, apart from alterations in the osmotic properties of its cell-sap, are efficient to give

rise to appreciable changes in its turgidity; and the belief that they do act in such

a fashion is simply based on tho arbiti-aiy assamption that tho excreise of contractile

function-that mere change of form in the living elements of a tissue-is capable of

giving use to alterations in its turgescence, wliioh, of comse, necessitates the second

assumption that the change in form is accompanied by a change in ffltrativc resistance.

Jho protoplasm m ammoniated leaves of i i k ^ t e has probably lost considerably in

filtrative resistance, and yet tho tissues retain a high degree of turgescence; whilst in

cases whore the leaves are exposed to tho iuflueuce of the vapom- of chloroform, tl!ere

IS no reason to suppose tliat there is any depression of filtrative resistance, and yet

total loss of turgescence occurs.

The belief that the essential determinant of turgescence Kos in cortain physical peculiarities

of protoplasm, and not in the properties of its products, and that any losses in

turgcscencc which are related to fnnetional causes are due to increased filtrative power

m tho protoplasts of a tissue, has no doubt, arisen because of the strikinc- iJuctuations

in turgosccnco accompanying depression or cessation of protoplasmic activity in cases

where the osmotic products of the latter, on the presence of which turgescence depends

are very unstable, and must therefore bo constantly renewed in order to the maintenance

ot tnrgrdlty. In the vast majority of cases, the protoplasmic products on which the colour

and turgescence ot tho tissues depend are very unstable, and hcnce any considerable

AKK. EOI. BOI. GAM). CiLcciTi Tor. TL