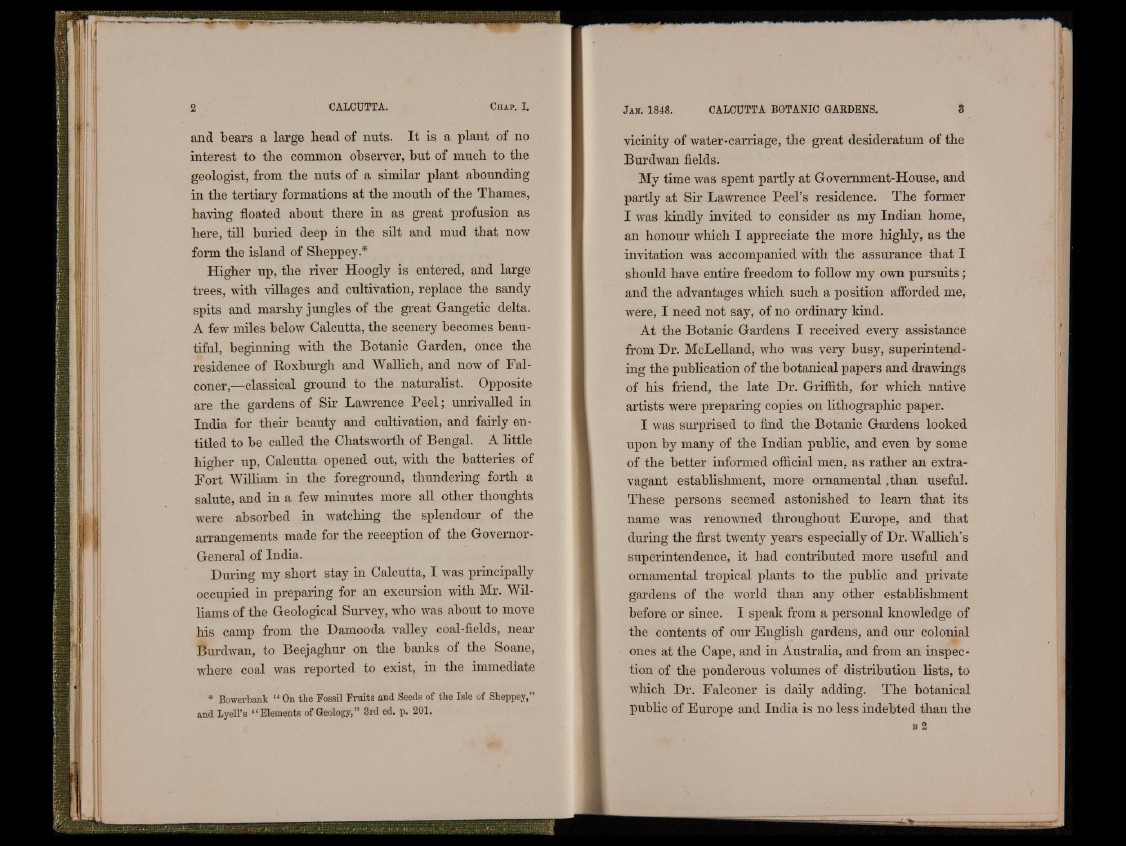

and bears a large head of nuts. I t is a plant of no

interest to the common observer, but of much to the

geologist, from the nuts of a similar plant abounding

in the tertiary formations at the mouth of the Thames,

having floated about there in as great profusion as

here, till buried deep in the silt and mud that now

form the island of Sheppey.*

Higher up, the river Hoogly is entered, and large

trees, with villages and cultivation, replace the sandy

spits and marshy jungles of the great Gangetic delta.

A few miles below Calcutta, the scenery becomes beautiful,

beginning with the Botanic Garden, once the

residence of Roxburgh and Wallich, and now of Falconer,—

classical ground to the naturalist. Opposite

are the gardens of Sir Lawrence Peel; unrivalled in

India for their beauty and cultivation, and fairly entitled

to be called the Chatsworth of Bengal. A little

higher up, Calcutta opened out, with the batteries of

Fort William in the foreground, thundering forth a

salute, and in a few minutes more all other thoughts

were absorbed in watching the splendour of the

arrangements made for the reception of the Governor-

General of India.

During my short stay in Calcutta, I was principally

occupied in preparing for an excursion with Mr. Williams

of the Geological Survey, who was about to move

his camp from the Damooda valley coal-fields, near

Burdwan, to Beejaghur on the banks of the Soane,

where coal was reported to exist, in the immediate

* Bowerbank “ On the Fossil Fruits and Seeds of the Isle of Sheppey,”

and Lyell’s “ Elements of Geology,” 3rd ed. p. 201.

vicinity of water-carriage, the great desideratum of the

Burdwan fields.

My time was spent partly at Government-House, and

partly at Sir Lawrence Peel’s residence. The former

I was kindly invited to consider as my Indian home,

an honour which I appreciate the more highly, as the

invitation was accompanied with the assurance that I

should have entire freedom to follow my own pursuits;

and the advantages which such a position afforded me,

were, I need not say, of no ordinary kind.

At the Botanic Gardens I received every assistance

from Dr. McLelland, who was very busy, superintending

the publication of the botanical papers and drawings

of his friend, the late Dr. Griffith, for which native

artists were preparing copies on lithographic paper.

I was surprised to find the Botanic Gardens looked

upon by many of the Indian public, and even by some

of the better informed official men, as rather an extravagant

establishment, more ornamental .than useful.

These persons seemed astonished to learn that its

name was renowned throughout Europe, and that

during the first twenty years especially of Dr. Wallich’s

superintendence, it had contributed more useful and

ornamental tropical plants to the public and private

gardens of the world than any other establishment

before or since. I speak from a personal knowledge of

the contents of our English gardens, and our colonial

ones at the Cape, and in Australia, and from an inspection

of the ponderous volumes of distribution lists, to

which Dr. Falconer is daily adding. The botanical

public of Europe and India is no less indebted than the

B 2