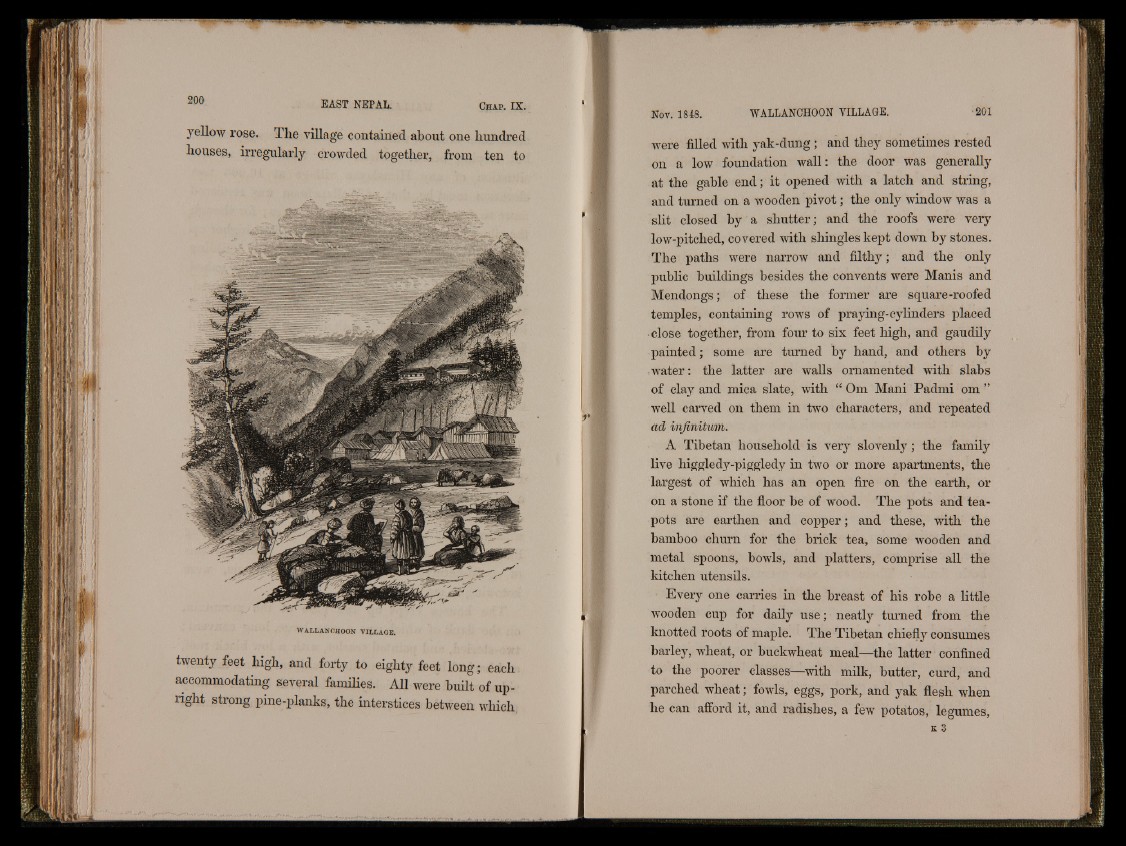

yellow rose. The village contamed about one hundred

houses, irregularly crowded together, from ten to

WALLANOHOON v il l a g e .

twenty feet high, and forty to eighty feet long ; each

accommodating several families. All were built of upright

strong pine-planks, the interstices between which

were filled with yak-dung; and they sometimes rested

on a low foundation wall: the door was generally

at the gable end; it opened with a latch and string,

and turned on a wooden pivot; the only window was a

slit closed by a shutter; and the roofs were very

low-pitched, covered with shingles kept down by stones.

The paths were narrow and filthy; and the only

public buildings besides the convents were Manis and

Mendongs; of these the former are square-roofed

temples, containing rows of praying-cylinders placed

close together, from four to six feet high, and gaudily

painted; some are turned by hand, and others by

water: the latter are walls ornamented with slabs

of clay and mica slate, with “ Om Mani Padmi om ”

well carved on them in two characters, and repeated

ad infinitum.

A Tibetan household is very slovenly; the family

live higgledy-piggledy in two or more apartments, the

largest of which has an open fire on the earth, or

on a stone if the floor be of wood. The pots and teapots

are earthen and copper; and these, with the

bamboo churn for the brick tea, some wooden and

metal spoons, bowls, and platters, comprise all the

kitchen utensils.

Every one carries in the breast of his robe a little

wooden cup for daily u se; neatly turned from the

knotted roots of maple. The Tibetan chiefly consumes

barley, wheat, or buckwheat meal—the latter confined

to the poorer classes—with milk, butter, curd, and

parched wheat; fowls, eggs, pork, and yak flesh when

he can afford it, and radishes, a few potatos, legumes,

K 3