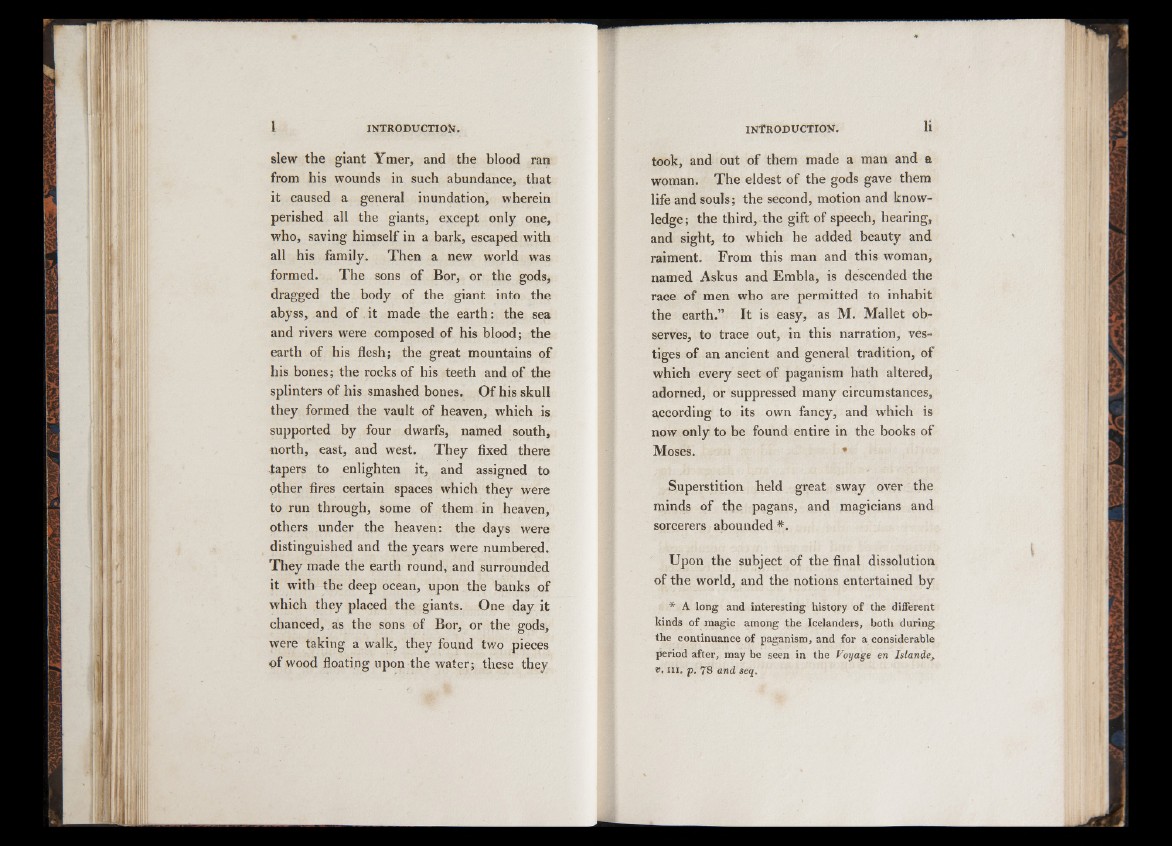

slew the giant Ymer, and the blood ran

from his wounds in such abundance, that

it caused a general inundation, wherein

perished all the giants, except only one,

who, saving himself in a bark, escaped with

all his family. Then a new world was

formed. The sons of Bor, or the gods,

dragged the body of the giant into the

abyss, and of it made the earth: the sea

and rivers were composed of his blood; the

earth of his flesh; the great mountains of

his bones; the rocks of his teeth and of the

splinters of his smashed bones. Of his skull

they formed the vault of heaven, which is

supported by four dwarfs, named south,

north, east, and west. They fixed there

tapers to enlighten it, and assigned to

other fires certain spaces which they were

to run through, some of them in heaven,

others under the heaven: the days were

distinguished and the years were numbered.

They made the earth round, and surrounded

it with the deep ocean, upon the banks of

which they placed the giants. One day it

chanced, as the sons of Bor, or the gods,

were taking a walk, they found two pieces

of wood floating upon the water; these they

took, and out of them made a man and a

woman. The eldest of the gods gave them

life and souls; the second, motion and knowledge;

the third, the gift of speech, hearing,

and sight, to which he added beauty and

raiment. From this man and this woman,

named Askus and Embla, is descended the

race of men who are permitted to inhabit

the earth.” It is easy, as M. Mallet observes,

to trace out, in this narration, vestiges

of an ancient and general tradition, of

which every sect of paganism hath altered,

adorned, or suppressed many circumstances,

according to its own fancy, and which is

now only to be found entire in the books of

Moses.

Superstition held great sway over the

minds of the pagans, and magicians and

sorcerers abounded *.

Upon the subject of the final dissolution

of the world, and the notions entertained by

* A long and interesting history of the different

kinds of magic among the Icelanders, both during

the continuance of paganism, and for a considerable

period after, may be seen in the Foyage en Istande,

v. h i. p. 78 and seq.