played. I t is made of bamboo reeds, and a gourd.

Tbe reeds are eight in number. They are fastened

into a gourd, the stalk of which is the mouth-piece

The pipes are from twelve to twenty inches in length,

and the fingers play upon the tops, like keys. I have

seen some with orifices in the sides of the pipes. I

notice only one in

this instrument.” Mr.

Carl Bock, who found

a similar instrument

among the tribes

of Dutch Borneo,

says, “ Mr. Augustus

Franks, of the British

Museum, has a

Chinese book in

which there is

figured an instru-

ment made in a

very similar manner.”

The one

which I engrave

is a far more

artistic and ela-

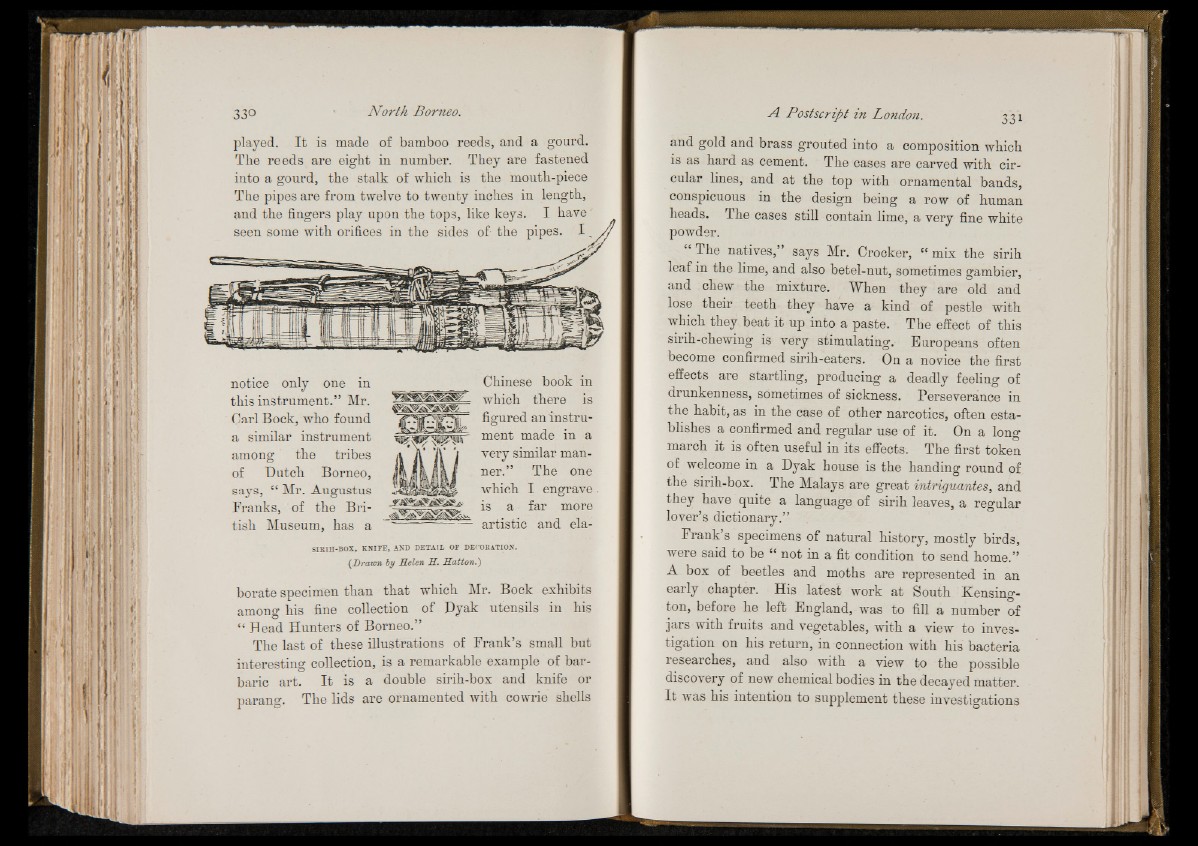

SIBIH-BOX, KNIFE, AND DETAIL OF DECORATION.

(Drawn by Helen H. Hatton.)

borate specimen than that which Mr. Bock exhibits

amono- his fine collection of Dyak utensils in his

“ Head Hunters of Borneo. ’

The last of these illustrations of Frank’s small but

interesting collection, is a remarkable example of barbaric

art. I t is a double sirih-box and knife or

parang. The lids are ornamented with cowrie shells

and gold and brass grouted into a composition which

is as hard as cement. The cases are carved with circular

lines, and at the top with ornamental bands,

conspicuous in the design being a row of human

heads. The cases still contain lime, a very fine white

powder.

“ The natives,” says Mr. Crocker, “ mix the sirih

leaf in the lime, and also betel-nut, sometimes gambier,

and chew the mixture. When they are old and

lose their teeth they have a kind of pestle with

which they beat it up into a paste. The effect of this

sinh-chewing is very stimulating. Europeans often

become confirmed sirih-eaters. On a novice the first

effects are startling, producing a deadly feeling of

drunkenness, sometimes of sickness. Perseverance in

the habit, as in the case of other narcotics, often establishes

a confirmed and regular use of it. On a long

march it is often useful in its effects. The first token

of welcome in a Dyak house is the handing round of

the sirih-box. The Malays are great intriguantes, and

they have quite a language of sirih leaves, a regular

lover’s dictionary.”

Frank s specimens of natural history, mostly birds,

were said to be “ not in a fit condition to send home.”

A box of beetles and moths are represented in an

early chapter. His latest work at South Kensington,

before he left England, was to fill a number of

jars with fruits and vegetables, with a view to investigation

on his return, in connection with his bacteria

researches, and also with a view to the possible

discovery of new chemical bodies in the decayed matter.

I t was his intention to supplement these investigations