headman conld only say two words of Malay (i.e.

bail, bail, tuan—“ Well, well, s ir ’’) ; but these he

repeated to me over and over again with great delight,

laughing the while to himself in excess of good nature.

Some empty tins and bottles, and a few yards (six) of

cloth, made us tremendous friends, and I left with my

men at nine o’clock, shaking hands all round, and get

ting four men to carry my things. We walked for a

long way up hill and down dale. The land was mostly

under cultivation with paddy (rice) and Indian corn,

which latter was very good eating. Now and.then we

passed through a wood with but little undergrowth ;

the trees, however, were very high, with long thm

stems. Stopped at twelve o’clock, as it was very hot,

at a house, and I drank a bottle of porter and ate a

pomolo (something like an enormous orange) with

much gusto. The natives were eager after the seeds

of the pomolo, and seemed to value them very much.

At 12.30 we continued our way, and arrived at

the Kudat Dusuns at one o’clock, a wretched house, the

dirt underneath the piles being only equalled by the

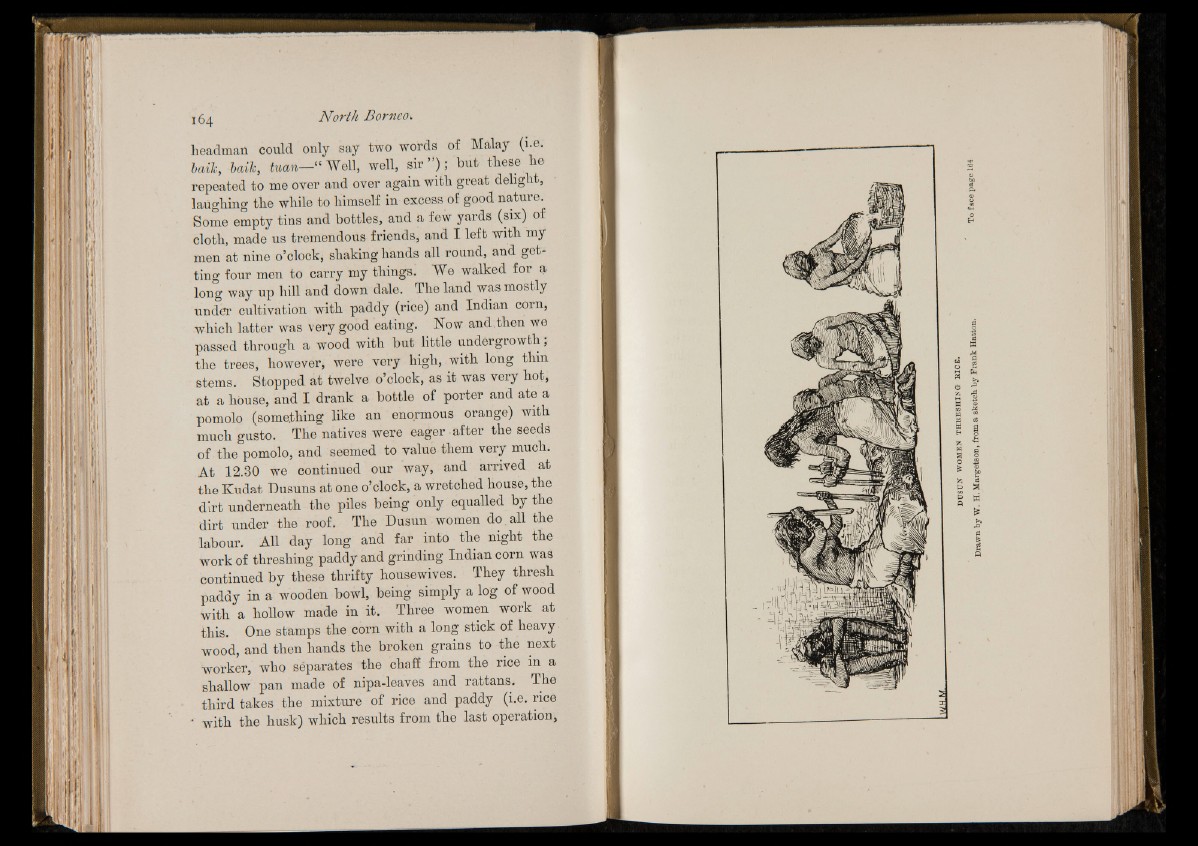

dirt under the roof. The Dusun women do. all the

labour. All day long and far into the night the

work of threshing paddy and grinding Indian corn was

continued by these thrifty housewives. They thresh

paddy in a wooden bowl, being simply a log of wood

with a hollow made in it. Three women work at

this. One stamps the corn with a long stick of heavy

wood, and then hands the broken grains to the next

worker, who séparâtes the chaff from the rice in a

shallow pan made of nipa-leaves and rattans. The

third takes the mixture of rice and paddy (i.e. rice

• with the husk) which results from the last operation,