boo, while the blades they contain are. worthy of a

Sheffield cutler. (1) A parang ; (2) the rough, clumsy

sheath of the rice-reaper; (3) the sheath of the handsome,

straight, beautifully balanoed parang blade in the

previous group; and (4) the last is a parang sheath

with a suggestion of artistic instinct which finds expression

in a little scroll cut with a knife at the end of

PARANGS AND REAPER-SHEATHS.

{Drawn by Helen H. Hatton.)

the scabbard, and in the dainty twisting of the rattan

bands. The parang is used for every purpose that a

knife can be put to, including the carving of blade

handles, raft-making, cutting up of game, and as a

weapon of warfare.

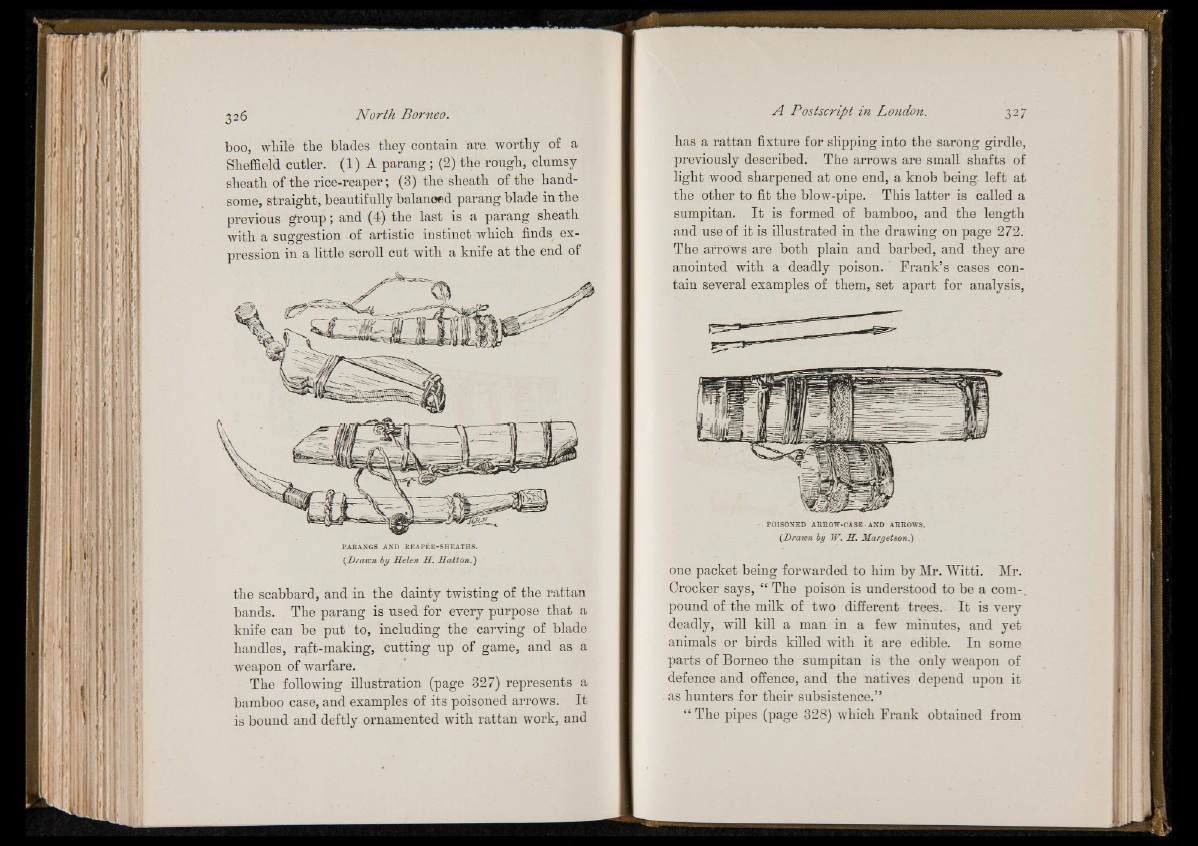

The following illustration (page 327) represents a

bamboo case, and examples of its poisoned arrows. I t

is bound and deftly ornamented with rattan work, and

has a rattan fixture for slipping into the sarong girdle,

previously described. The arrows are small shafts of

light wood sharpened at one end, a knob being, left at

the other to fit the blow-pipe. This latter is called a

sumpitan. I t is formed of bamboo, and the length

and use of it is illustrated in the drawing on page 272.

The arrows are both plain and barbed, and they are

anointed with a deadly poison. Frank’s cases contain

several examples of them, set apart for analysis,

POISONED ARROW-CASE AND ARROWS.

(Drawn by W. H. Margetson.)

one packet being forwarded to him by Mr. Witti. Mr.

Crocker says, “ The poison is understood to be a com-,

pound of the milk of two different trees. I t is very

deadly, will kill a man in a few minutes, and yet

animals or birds killed with it are edible. In some

parts of Borneo the sumpitan is the only weapon of

defence and offence, and the natives depend upon it

as hunters for their subsistence.”

“ The pipes (page 328) which Frank obtained from