I was carried some distance on the back of Housin,

my mandore, over swamps and mud, until we got

to the Hadji’s house. He, the Hadji, lives on a

high hill, and I think he is rather a scamp. He

knows too much. He tried to intimidate me, I think,

for he said the jungle path was very bad, up to one’s

waist in mud, rain, and slush; also that there are many

snakes, and some very big ones. We soon, however,

found out the truth of the mud part of his warnings.

(He also said that he had heard that silver had been

found somewhere in the country.) The discomforts

of the afternoon were very great. For miles through

swamp, walking with clay over one’s boot-tops, and

often sinking up to one’s knees in mud and water.

Wet grass coming up to one’s .shoulders, and rain

falling all the way, added to the other miseries of the

journey. I got two Dusuns at the Hadji’s, who helped

to carry my things. . I t was curious to see the rate

they got along at, barefooted and loaded as they were

with heavy burthens. At three o’clock we arrived at

a large Dusun house, like the one figured in Wallace’s

“ Australasia,”-—exterior of a Dyak village. I should

think a hundred men lived there, with their wives

and families. The headman was kind to u s; he

brought eggs, bananas, sugar-cane for the men,

water, and other things. The house is really an immense

dormitory, there being one long passage with

all the rooms opening out on it, the other side being

occupied by a kind of verandah, which was given

to us. I was simply a nine-days’ wonder. My boots,

my socks, clothes, hammock, my beer, biscuits, and

the way I ate with a knife and fork and plate, all were

objects of extreme curiosity. When I slept, the whole

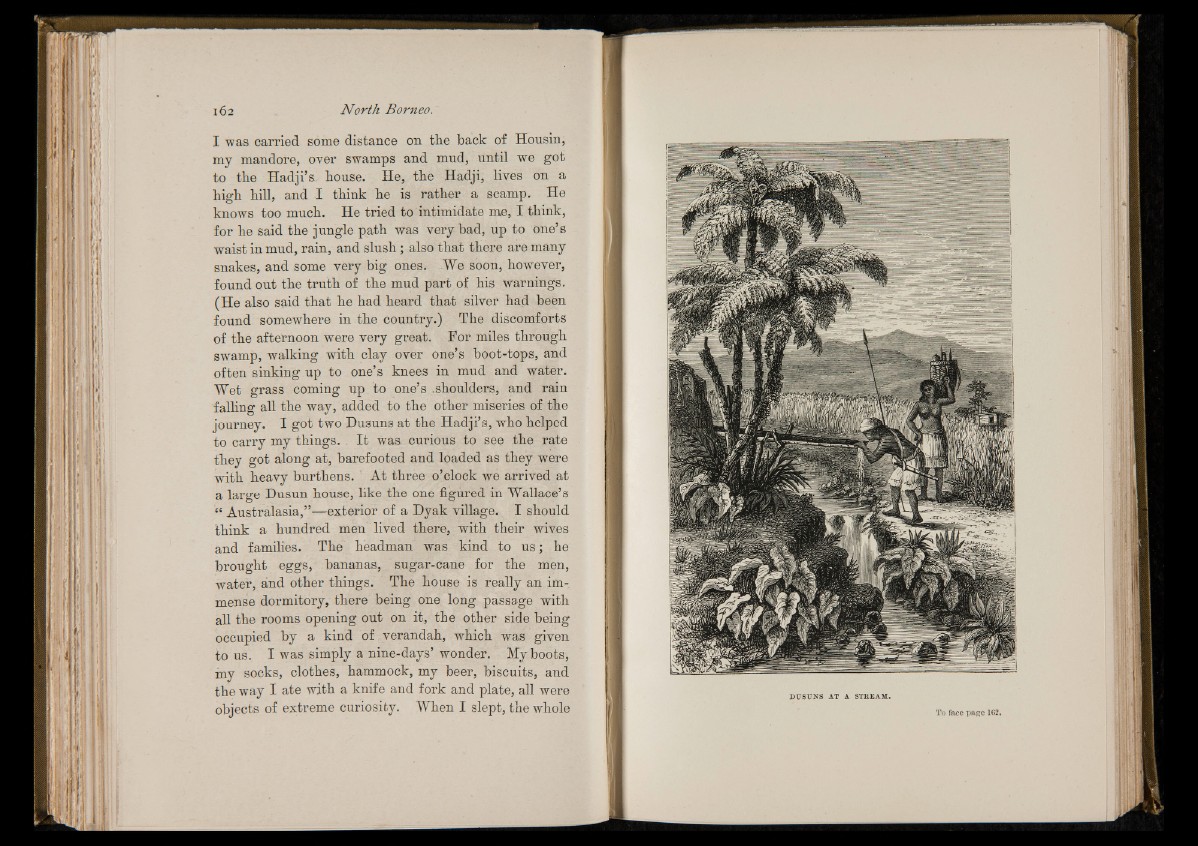

DUSUNS AT A STREAM.

To face page 162.