and its sky overhung with gray threatening-looking cloud, is

one that extends from just below Cameroons to Angola,

i.e., to the edge of the Kalahari desert, where wet seasons

are not; it strikes the person coming south from the Bights,

where the dry season is the hot season and the wet the cooler,

as most strange and peculiar. One of the many difficulties of

travelling down the West African coast is that you are certain

to get your season wrong somewhere. It is not so bad for me

as it is for some people, because I rather prefer the wet and am

reconciled to the climate. Now a person with a predilection for

dry seasons has an awful life of it, and I must in justice remark

that this predilection is the sane one to possess. I know

an American gentleman, who “ ’lowed he’d do West Africa,”

but ultimately “ ’lowed West Africa had done him,” who got

so bothered by the different times different seasons were going

on in different parts of the Coast that he characterised the

entire West African climate as “ a fried eel.” Why fried I do

not know. We do not fry in the Coast climate, we stew,—

and I consider the statement harsh. Of course we have got

the worst climate in the world and we are proud of it. Some

day I will write a work in ten volumes that will be an ABC

of the whole affair, and be what my German friends would call

the essential pocket-book for West African travellers, and it

will let them know what to expect, when, where, and how ; but

meantime I may note that both wet and dry seasons have

their points. If you want to go far up a river, without

having ample opportunities of studying the various ways in

which your craft can get wrecked on sandbanks, you must go

in thé full wet. Of course this ends in your returning, or

attempting to return in the dry, and as when you have penetrated

the interior any distance you usually start on your

return journey full tilt, pursued by rapacious and ferocious

cannibals, the fact that you stick on sandbanks on an

average three times in a mile, gives you considerable worry.

I f you wish to penetrate the interior on foot, you must choose

the dry season because of those swamps— a good bottomless

swamp is impassable in the wet. In the dry it bears a crust

over it, which, with suitable precautions, can be crossed, while

the shallow swamps can be waded. And all the rivers are

navigable in canoes in the dry, if too shallow for steamers, and

canoes are the most comfortable things to travel in in the

whole world. The predilection in favour of small steam

launches is to me a mystery. What joy any sane person

can have in one, who is not in a hurry, I do not know. I

have had some experience in them, and some of those e x periences

have been the

worst I have gone

through. I remember one

occasion when I tried to

get a little launch through

a creek which was, although

deep, full of water

grass. W e ll! I will be

careful, but it was enough

to make my distinguished

Liverpool friends

use bad language. You

see you could not get the

screw to work because of

the grass. Attempts at

using the screw merely

made the poor thing into

a chaff cutter, and it was

not made for that, so

■choked. You could not

get up a sail, because there

was no wind sufficiently

strong Jo get through the

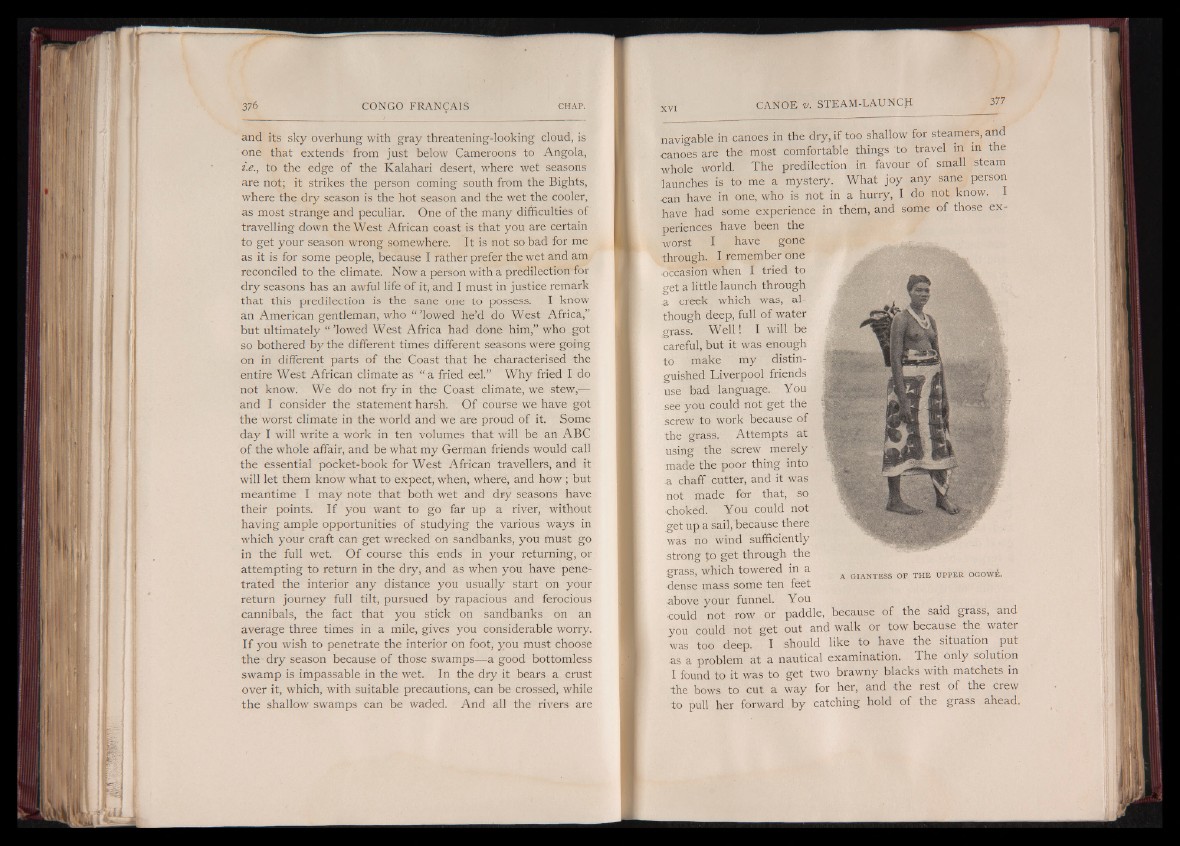

grass, which towered in a ^ GIANTESS 0F t h e u p p e r o g o w e .

•dense mass some ten feet

above your funnel. You

could not row or paddle, because of the said grass, and

you could not get out and walk or tow because the water

was too deep. I should like to have the situation put

as a problem at a nautical examination. The only solutipn

I found to it was to get two brawny blacks with matchets in

the bows to cut a way for her, and -the rest of the crew

to pull her forward by catching hold of the grass ahead.