its light with us, and we sat round our fire surrounded by an

utter darkness. Cold, clammy drifts of almost tangible mist

encircled us ; ever and again came cold faint puffs of wandering

wind, weird and grim beyond description.

The individual names of the mountains round Kondo Koiido

and above I cannot give you,. though I was told them. For

in my last shipwreck before reaching Kondo Kondo, I had

lost my pencil ; and my note-book, even if I had had a

pencil, was unfit to get native names down on, being a pulpy

mass, because I had kept it in my pocket after leaving the

Okana river so as to be ready for sübmergencies. And I also

had several fish and a good deal of water in my pocket too,

so that I am thankful I have a note left.

I will not weary you further with details of our ascent of the

Ogowé rapids, for I have done so already sufficiently to make

you understand the sort of work going up them entails, and

I have no doubt that, could I have given you a more vivid

picture of them, you would join me in admiration of the fiery

pluck of those few Frenchmen who traverse them on duty bound.

I personally deeply regret it was not my good fortune to meet

again the French official I had had the pleasure of meeting on

the Éclaireur. He would have been truly great in his description

of his voyage to Franceville. I wonder how he would

have “ done ” his unpacking of canoes and his experiences on

Kondo Kondo, where, by the by, we came across many of

the ashes of his expedition’s attributive fires. Well ! he must

have been a pleasure to Franceville, and I hope also to the

good fathers at Lestourville, for those places must be just

slightly sombre for Parisians.

Going down big rapids is always, everywhere, more dangerous

than coming up, because when you are coming up and

a whirlpool or eddy does jam you on rocks, the current helps

you off— certainly only with a view to dashing your brains out

and smashing your canoe on another set of rocks it’s got ready

below ; but for the time being it helps, and when off, you take

charge and convert its plan into an incompleted fragment ;

whereas in going down the current is against your backing off.

M’bo had a series of prophetic visions as to what would happen

to us on our way down, founded on reminiscence and tradition.

I tried to comfort him by pointing out that, were any one of his

prophecies fulfilled, it would spare our friends and relations all

funeral expenses; and, unless they went and wasted their money

on a memorial window, that ought to be a comfort to our well-

regulated minds. M’bo did not see this, but was too good a

Christian to be troubled by the disagreeable conviction that was

in the minds of other members of my crew, namely, that our

souls, unliberated by funeral rites from this world, would have to

hover for ever over the Ogowe near the scene of our catastrophe.

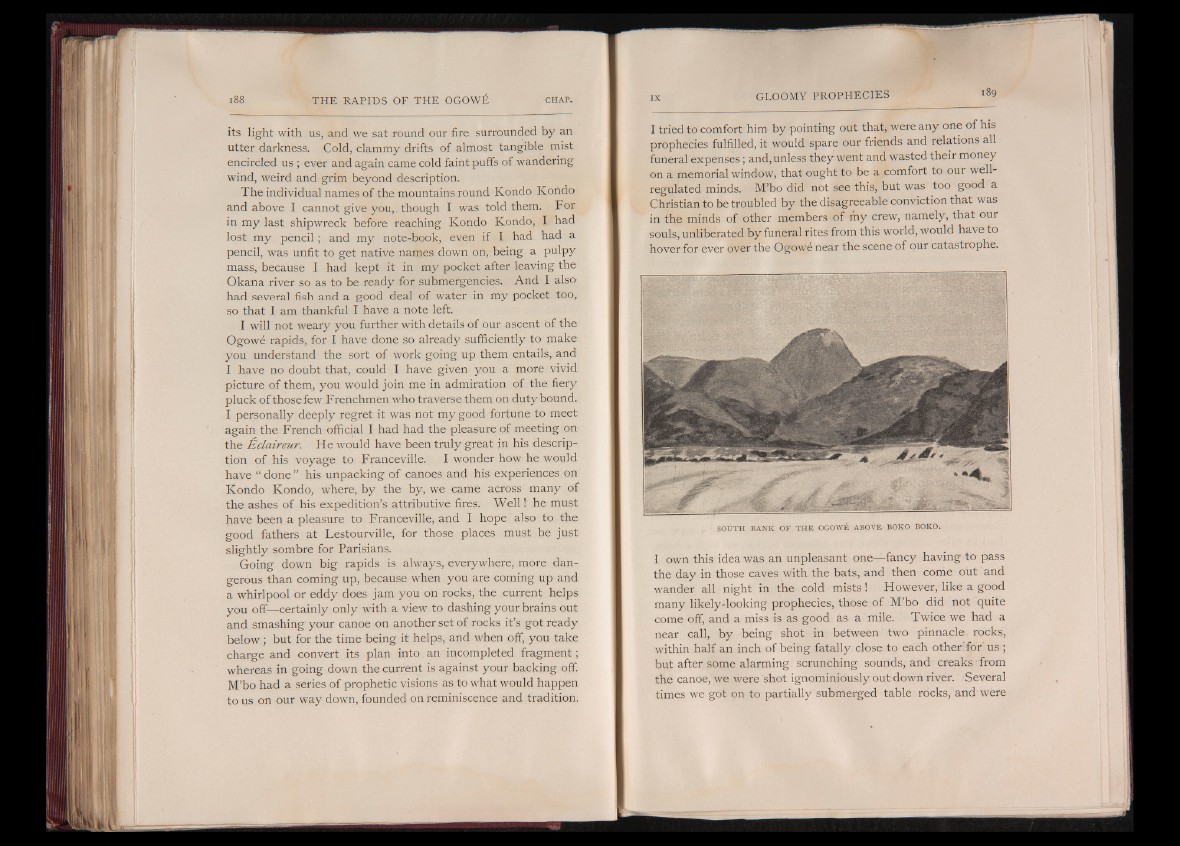

S O U T H B A N K O F T H E O G O W E A B O V E B O K O B O K O .

I own this idea was an unpleasant one— fancy having to pass

the day in those caves with the bats, and then come out and

wander all night in the cold mists! However, like a good

many likely-looking prophecies, those of M’bo did not quite

come off, and a miss is as good as a mile. Twice we had a

near call, by being shot in between two pinnacle rocks,

within half an inch of being fatally close to each other for us ;

but after some alarming scrunching sounds, and creaks from

the canoe, we were shot ignominiously out down river. Several

times we got on to partially submerged table rocks, and were