and thirty appeared in quick succession,’ so quickly, Mr. Coward tells me, that it

was almost impossible to count them.

Most Bats which I have kept in confinement went through the same manoeuvres

when awaking from sleep, and Noctules are no exception to the general rule.

A slight muscular twitching is first noticeable, affecting the whole body; the head

is moved slowly from side to side, and the minimal begins to pant. Gradually the

actions increase until, as the heart gains power, the little creature pumps and

pants as if it were in the throes of a fit. Then the eyes open and the head is

raised, the temperature, having risen enormously, and the Bat is awake. Generally

the process of. waking takes from ten to fifteen minutes, but in some species it is

much quicker than in others. Probably the act of waking takes less time if the Bats

are disturbed near the hour when they should normally rouse up for the evening,

and certainly a Bat wakes, as a general rule, with greater rapidity in summer than

in winter. Noctules often are fully awake in a minute or two, and Mr. Oldham’s

remarks about some which he obtained from a beech confirm this. ‘ At 7.15,

some three-quarters of an hour before their time of flight (on May 8), the jarring

of a ladder against the tree caused some of the Bats to squeak. When I broke

away the dead wood, however, and exposed them to the daylight, they made no

attempt to escape, but remained huddled together in a comatose condition in the

upper part of the cavity, their low temperature during sleep being .apparent when

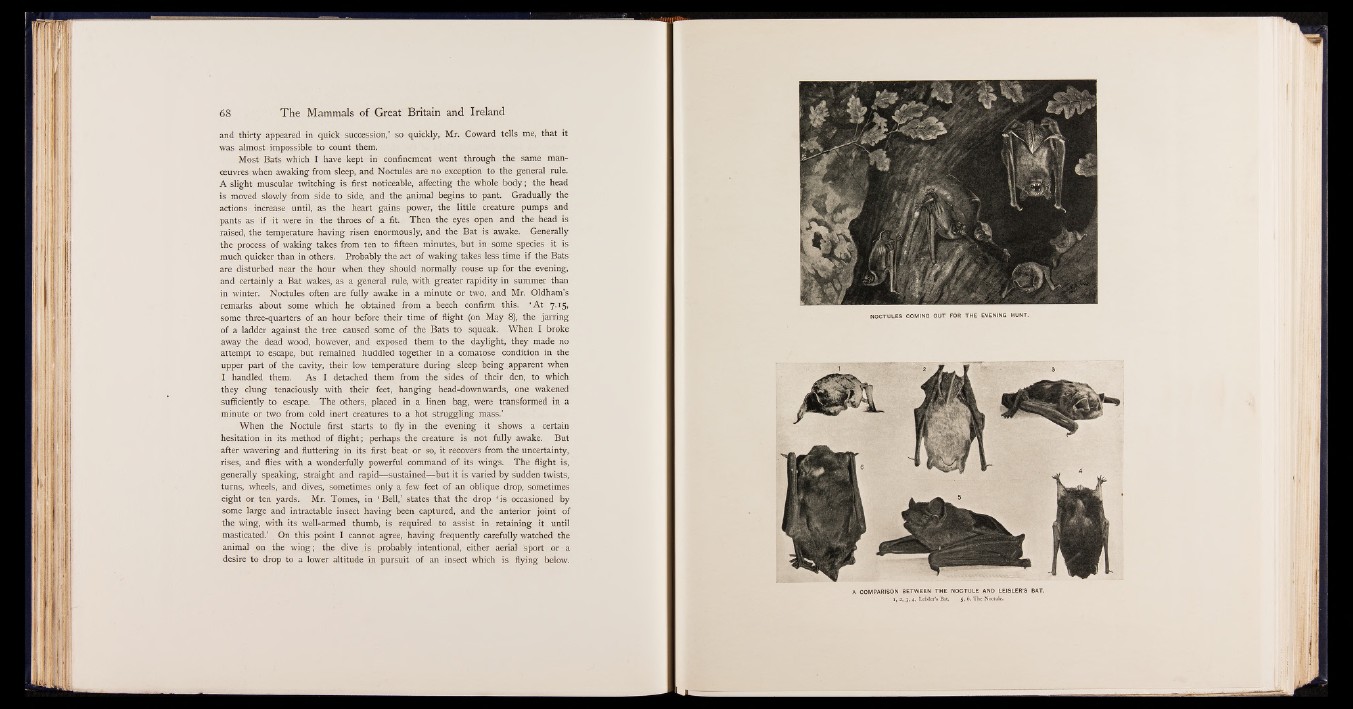

I handled them. As I detached them from the sides of their den, to which

they clung tenaciously with their feet, hanging head-downwards, one wakened

sufficiently to escape. The others, placed in a linen bag, were transformed in a

minute or two from cold inert creatures to a hot struggling mass.’

When the Noctule first starts to fly in the evening it shows a certain

hesitation in its method of flight ; perhaps the creature is not fully awake. But

after wavering and fluttering in its first beat or so, it recovers from the uncertainty,

rises, and flies with a wonderfully powerful command of its wings. The flight is,

generally speaking, straight and rapid— sustained— but it is varied by sudden twists,

turns, wheels, and dives, sometimes only a few feet of an oblique drop, sometimes

eight or ten yards. Mr. Tomes, in ‘ Bell,’ states that the drop ‘ is occasioned by

some large and intractable insect having been captured, and the anterior joint of

the wing, with its well-armed thumb, is required to assist in retaining it until

masticated.’ On this point I cannot agree, having frequently carefully watched the

animal on the wing; the dive is probably intentional, either aerial sport or a

desire to drop to a lower altitude in pursuit of an insect which is flying below.